- | Government Spending Government Spending

- | Expert Commentary Expert Commentary

- |

ACA Will Drive Health Care Costs Up

Our best information remains that the ACA, by expanding Medicaid as well as other subsidized insurance, didn’t merely shift more of the burden of funding existing health care costs to taxpayers– it actually increased those costs.

Today the Mercatus Center unveiled a study by Bradley Herring (Johns Hopkins University) and Erin Trish (University of Southern California) finding that the much-discussed health spending slowdown that continued in 2010-13 “can likely be explained by longstanding patterns” over more than two decades, rather than suggesting a recent policy correction. Projecting these factors forward and incorporating the effects of the Affordable Care Act’s health insurance coverage expansion provisions, Herring-Trish predict the expansion will produce a “likely increase in health care spending.”

Though not surprising in light of longstanding appreciation of insurance’s effects on health service utilization, the latter finding is nevertheless profoundly concerning given that pre-ACA health spending growth trends were already widely held to be untenable. These Herring-Trish findings were first made public last December in Inquiry: the Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision and Financing and warrant the attention of policymakers, for the simple reason that they show core ACA provisions as worsening some of the most severe problems in health care policy.

The run-up to the ACA’s passage featured widespread recognition that excess health cost growth was a substantial problem afflicting entities ranging from the federal government to health insurers to individual Americans. Sometimes the argument was taken too far, as in CBO’s erroneous 2008 depictionof health cost inflation being the dominant driver of federal budget deficits. But experts on all sides agreed that national health spending was growing faster than our economy’s ability to support it, and that this was a significant public policy problem requiring correction.

Experts have also long understood that insurance coverage tends to fuel additional health service utilization, driving up spending. This has long been evident from academic studies and has been incorporated into many models for projecting health spending. The Medicare trustees’ projections reflect this understanding of insurance effects; essentially, the more that insurance coverage reduces out-of-pocket costs, the more health spending there will be (all other things being equal). This is good when it means more people can afford health services they need; it’s bad when it prompts the purchase of services people don’t need and wouldn’t choose to buy unless so incented. Good or bad, it’s a reality; more insurance generally means more spending.

Public understanding of this phenomenon became somewhat confused when the ACA was debated. Two objectives of the ACA were too often conflated:

1) expanding the pool of insured so that sick people could have their health care costs subsidized by healthy people, and

2) bending the health cost curve down.

Pursuing the first objective is unhelpful to the second objective. Granted, requiring healthy individuals to carry insurance (and imposing community rating, as the ACA does) can reduce costs facing those with expensive health conditions. This is because the healthy then contribute more money to insurance plans than they take from them, permitting others to pay for less than they receive. However, expanding coverage does not drive total costs down but rather up. This is because all the costs of caring for the sick are still there, while all insured persons have greater incentive to utilize more health services than they would if uninsured.

Given how the ACA’s advocates touted the law as “bending the health care cost curve [down], and reducing the deficit” while occasionally in the same sentence crediting it with expanding coverage to “more than 94 percent of Americans,” many Americans could be forgiven for not understanding those two goals were in conflict.

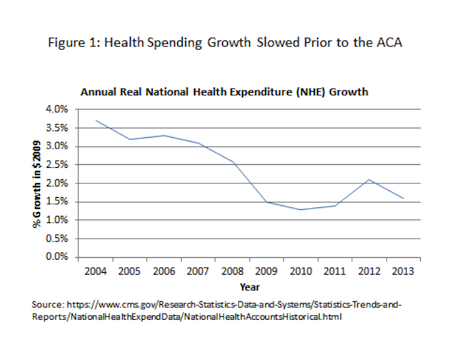

National health expenditure growth began to slow significantly prior to the ACA’s passage in 2010 (see Figure 1). The slowdown continued after the ACA was passed but before many of its provisions took full effect, tempting some advocates to credit the ACA somewhat groundlessly for successful cost containment.

Herring-Trish show that the vast majority of the recent slowdown can be explained by “long-standing patterns” involving trends in real income, physicians per capita, the percent of the population living in nonmetropolitan areas, the numbers of those living in poverty, and other factors. If these trend lines are traced back to 2000, Herring-Trish find that they account for over 70% of the recent cost slowdown. If they are traced back to 1991, they account for virtually all of it (98%). By itself, the Great Recession’s effect of reducing average real incomes accounted for more than two-fifths of the deceleration in health spending.

Moreover, not only has the ACA not contributed meaningfully to the recent cost slowdown, but it will likely put upward pressure on health spending going forward. Herring-Trish find that the law’s Medicaid expansion will by itself increase total national health spending roughly 1% by 2019. A 1% increase may sound small, but remember we already spend over $3 trillion a year on health care, and faced unsustainable cost growth trends before the ACA’s coverage expansion added to them.

In fairness it should be acknowledged there are other provisions of the ACA that its advocates hoped would counteract the coverage expansion’s effect of adding to total health costs. However, many of those measures, from the Cadillac plan tax to the Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB), have not produced their desired savings because they have not taken effect and it’s uncertain that they ever will. Our best information remains that the ACA, by expanding Medicaid as well as other subsidized insurance, didn’t merely shift more of the burden of funding existing health care costs to taxpayers– it actually increased those costs. Sooner or later, lawmakers will need to fix that problem.