- | Housing Housing

- | Expert Commentary Expert Commentary

- |

Craft Brewing Has Brought Variety to Oktoberfest

Overall the craft beer renaissance has been a success: In many states tasty local beer is widely available and consumers have more choices than ever before. But further deregulation will foster additional competition and ensure that future generations of beer lovers will never again be limited to MillCoorWeiser at their Oktoberfest celebrations or backyard BBQs.

The annual Oktoberfest celebration is upon us and millions of people throughout the U.S. and around the world will attend local festivals in addition to the official celebration in Munich, Germany. Perhaps nothing is more closely associated with Oktoberfest than beer, and Oktoberfest revelers in the U.S. have a plethora of tasty beer options to choose from.

But it wasn’t too long ago that American beer drinkers were largely limited to what beer buffs call MillCoorWeiser beer—the mass produced American lager most prominently sold under the Budweiser, Miller, and Coors brand names. In their 2015 article, Economists Kenneth G. Elzinga, Carol Tremblay and Victor J. Tremblay (Elzinga et al.) report that prior to 1970 over 99% of the beer consumed in the U.S. was the traditional lager beer produced by the large domestic breweries. Needless to say, it was a bland time for American beer.

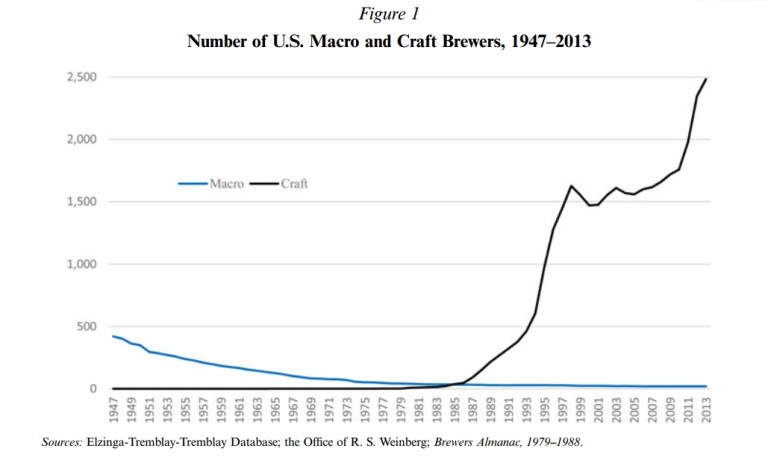

Then in 1965, entrepreneur and innovator Fritz Maytag purchased the failing Anchor Brewing Company, located in San Francisco, and the revival of craft beer was under way. Maytag revived the brewery, and according to Elzinga et al. his operation inspired other entrepreneurs to join him in the craft beer renaissance. Federal tax changes also helped; in 1978 Congress reduced the levy on small brewers from $9 per barrel to $7 per barrel for the first 60,000 barrels produced by breweries with less than 2 million barrels in total sales, an event that Elzinga et al. call a “windfall for craft brewers.” Though growth was slow at first, in the mid-1980s the number of craft brewers exploded, as shown in the figure below.

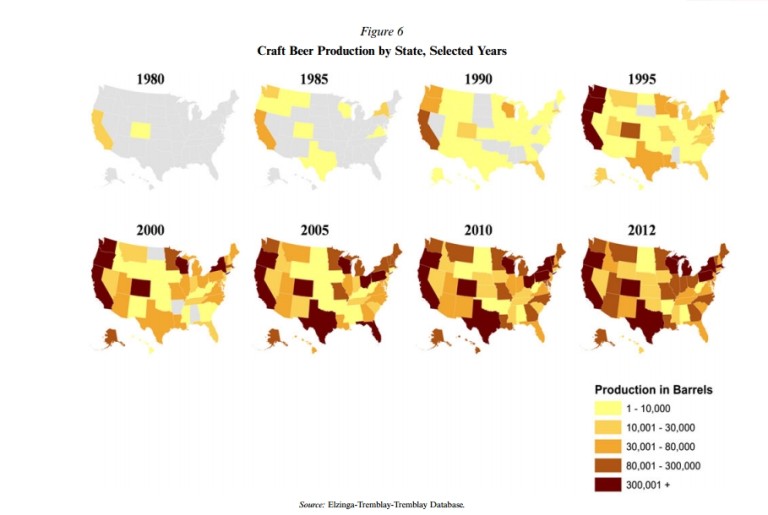

Yet despite this drastic increase in craft brewers, not everyone was able to enjoy the new varieties of beer right away. The craft beer renaissance started in California, and in 1980 97% of craft beer was produced there. Only one brewer, Boulder Brewing of Colorado, was outside the state. The figure below from Elzinga et al. shows the spread of craft beer production eastward and northward, with the south being the last region to produce its own craft beer.

So why did the craft beer renaissance start in California? As Elzinga et al. put it, some of it was chance: Fritz Maytag happened to be a graduate student at Stanford when Anchor Brewing was put up for sale, and he had the financial and human capital to revitalize the company. Early craft brewers also knew that they couldn’t compete with the macro breweries on price due to economies of scale, so they looked to create a more upscale product. Jack McAuliffe, who founded New Albion Brewing Company in Sonoma, CA in 1976, was one of the first to recognize the demand for craft beer as a drink to be paired with food—similar to wine—due to his proximity to Northern California wine country.

California also had a relatively developed taste for craft beer. A disproportionate number of Californians home-brewed their own beer during this period, despite it being illegal to do so until 1979. Since these home brewers were already brewing darker and heavier-style beers and ales on their own there was an established market for craft brewers to sell to.

The abundance of home brewers also created an environment that encouraged learning by doing, experimentation and knowledge sharing. Several craft-brewing pioneers, including Sierra Nevada Brewing Company founder Ken Grossman, visited Maytag’s facility to learn about the business.

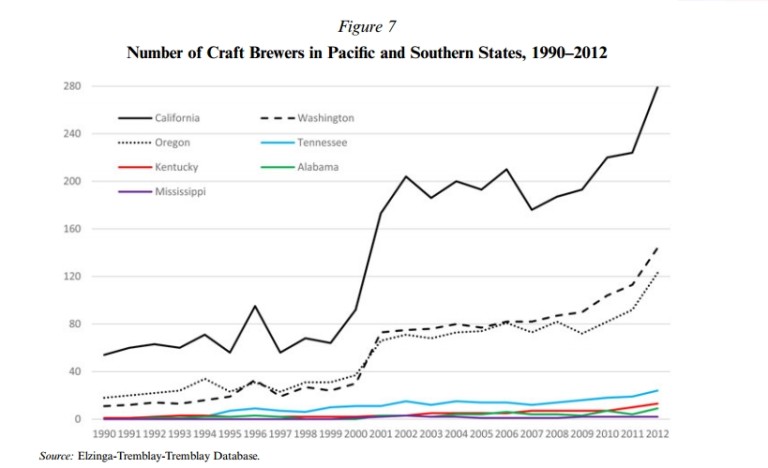

The early start and expansion of craft brewing in California and the West is still apparent today, as shown in the figure below from Elzinga et al.; the Pacific states of California, Oregon and Washington have many more craft brewers than the Southern states of Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee and Alabama.

State and local policy also helps explain the distribution of craft beer production. Fifteen states give a tax break to smaller brewers, including Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania and New York, and each of these states produced over 300,000 barrels in 2012 (see Figure 6). In their multivariable regression analysis, Elzinga et al. find that a higher state per-barrel excise tax leads to less beer production and less craft brewers, all else being equal.

Elzinga et al. also find that there are more craft brewers and more beer production in states that allow brewpubs, which they use as a proxy for craft beer regulation in general. Additional research also shows that state-level regulations such as self-distribution limits, which prevent brewers from selling their beer directly to retailers, and franchise distribution laws, which regulate the brewer-wholesaler relationship, reduce the number of breweries in a state. The repeal or modification of such regulations would enable more competition and further increase the choices available to consumers looking for the perfect pint of beer.

Overall the craft beer renaissance has been a success: In many states tasty local beer is widely available and consumers have more choices than ever before. But further deregulation will foster additional competition and ensure that future generations of beer lovers will never again be limited to MillCoorWeiser at their Oktoberfest celebrations or backyard BBQs.