- | Healthcare Healthcare

- | Expert Commentary Expert Commentary

- |

Did The Supreme Court Ruling Render the Health Law's Finances Untenable?

It is quite possible that this week’s Supreme Court ruling has just changed the 2010 health care law in such a way that it will add substantially to federal deficits from almost any vantage point. We will know more after the Congressional Budget Office completes its analysis.

It is quite possible that this week’s Supreme Court ruling has just changed the 2010 health care law in such a way that it will add substantially to federal deficits from almost any vantage point. We will know more after the Congressional Budget Office completes its analysis.

Let’s review the background. CBO’s last complete score of the health care law, in March 2011, found that it would reduce federal deficits by $210 billion from 2012-2021. That was before the suspension of the CLASS program provision, which takes the positive score down to $123 billion. As I pointed out in my recent study, those scores are not relative to actual prior law but to a hypothetical budget baseline scenario that CBO uses under the procedures of the Deficit Control Act. Relative to actual prior law, by contrast, the health law -- had it been upheld in its entirety -- would add more than $340 billion to federal deficits over the next ten years.

Let’s nevertheless reference the positive score of $123 billion here since, flawed or not, it’s what arises under Congress’s scorekeeping rules. If this week’s ruling worsens the bill’s budget impact by more than $123 billion over ten years, then the legislation adds to federal deficits even by the standard adopted by its proponents. Will this score remain positive after the Supreme Court ruling?

The Supreme Court left intact most of the health care law’s provisions, excepting only one section that would have allowed the Secretary of HHS to withdraw “existing Medicaid funding” from states that fail to comply with the law’s expansion of Medicaid eligibility.

This is important. At first glance, it appears quite possible that this decision could:

- Considerably worsen the budgetary effects of the law, and;

- Result in substantial cuts, later in this decade, to the subsidies for low-income individuals who are compelled to buy health insurance under the law.

Here’s why:

The health law’s coverage expansion contains two big components: an expansion of Medicaid/CHIP and new federally-subsidized health insurance exchanges. The Medicaid expansion extends coverage to Americans of up to 133 percent of the federal poverty line, but with a 5 percent income exclusion that brings the effective eligibility level up to 138 percent. Participants in the other program -- the new health exchanges -- are generally eligible for federal subsidies if they have incomes from 100 percent to 400 percent of the poverty line, provided that the individual is not qualified for Medicaid/CHIP, certain other health benefits, or “affordable” employer-provided coverage.

The interaction between these two avenues to subsidized coverage – Medicaid and the health exchanges – has important fiscal effects.

Twenty-six states acted as plaintiffs in the lawsuit against the Affordable Care Act, in part based on its Medicaid expansion. Their argument was that the federal government could not force states to expand Medicaid coverage via the threat of revoking existing Medicaid funding. The Supreme Court has now ruled that the federal government cannot make good on that threat.

One can make an argument that it is still in these states’ interest to expand Medicaid, since under the 2010 law the federal government will pick up the tab in the first few years. But what matters is whether the states believe it is in their interest to accept the long-term costs associated with the expansion. It is reasonable to conjecture that, having fought to be freed from being forced to do so, some of these 26 states will not expand Medicaid coverage as envisioned by the health law. This means that Medicaid coverage will be substantially lower than CBO projected in its last evaluation.

It also means that subsidized participation in the health exchanges will likely be higher than last projected. Consider an individual at 125% of the poverty line, in a state that now chooses not to expand Medicaid coverage. Before, CBO would have anticipated that this individual would be on Medicaid. Now it’s possible that the individual will be getting subsidies through the health exchanges.

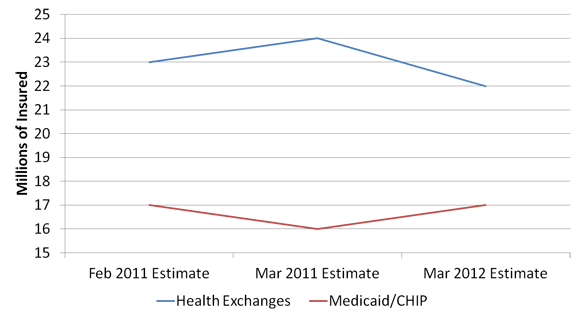

We can see these interactive effects in the evolution of past CBO scores of the health legislation. Depending on its projections for future economic performance, CBO projects a certain number of people to be Medicaid-eligible. Whenever CBO thinks more people will be on Medicaid, it finds that fewer people will be covered under the law’s exchanges, and vice versa. See the following graph.

Just to be clear: All of the estimates on this graph pertain to CBO projections for the single future year of 2020. The different points on the graph represent estimates made by CBO respectively in February 2011, March 2011, and March 2012.

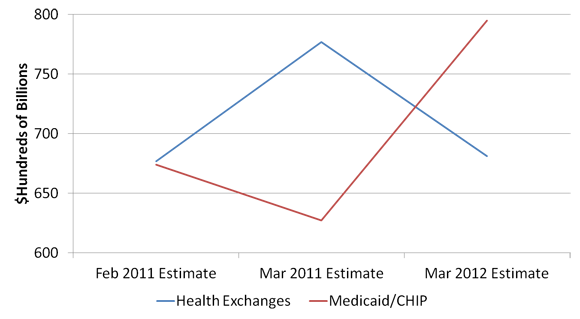

The movements in these estimates may not seem large, but they have significant ramifications for the cost of the health care law. Here are the estimates for the gross costs of the Medicaid/CHIP expansion in comparison with the health exchanges, which have varied significantly with the participation assumptions.

As can be seen above, the participation assumptions have a significant effect on the relative cost of each part of the health law. This is primarily because the law’s health exchange subsidies are much more generous for individuals near 133% of the poverty line than they are for those with higher incomes. Thus, the average cost of the subsidies grows significantly when they are provided to more individuals who might otherwise have gone onto Medicaid.

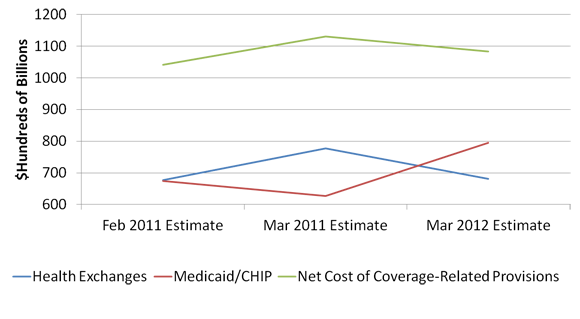

Where this becomes most striking is in examining the effect of Medicaid participation on the net cost of the health law, which incorporates other factors such as small employer tax credits, and revenues from penalties (now taxes, per the Supreme Court) assessed on individuals and employers. As the graph below shows, the net estimated cost of the coverage expansion has risen and fallen inversely with the proportion of individuals projected to get their coverage from Medicaid.

Total Coverage Expansion Costs, 2012-21

The graph above also shows that as the expected proportion in the exchanges has risen (and fallen), so has the total projected net cost of the law. It could thus well be that if the court’s decision shifts coverage from Medicaid to the new health exchanges, the law’s budgetary effects may be much worse than last projected.

How much worse? No one (perhaps outside of CBO) can say. But under past estimates, a 1 million-person reduction in the law’s reliance on Medicaid has meant an increase in net costs of about $50-$90 billion over ten years. With 26 states joined in a lawsuit to be released from this forced coverage expansion, the fiscal worsening could be substantial.

The side effects of the court ruling don’t end there. The health law also contains a “fail safe” provision requiring that total costs of the health exchange credits be limited to 0.504% of GDP per year after 2018. In previous estimates, CBO projected that subsidy percentages would “eventually” be cut by this provision to keep their total costs beneath this cap. But if health exchange participation is to be significantly higher than previously projected, then costs will be also much higher. This would force significant cuts in subsidies to low-income individuals starting in 2019; the text of the law is explicit that the cap will be enforced by reducing these subsidies. Lawmakers would thus have to choose between allowing these cuts to low-income individuals to go into effect, and waiving the existing fiscal constraints of the health care law.

Much attention has been given to the argument that without the individual purchase mandate, other parts of the health care law would become unworkable. Much less attention has been given to the fact that without the states forced to be on board with the Medicaid expansion, the law’s health exchange subsidies might be fiscally unworkable. The Supreme Court may have just set in motion of chain of events that could lead to the law’s being found as busting the budget, even under the highly favorable scoring methods used last time around.