- | Government Spending Government Spending

- | Expert Commentary Expert Commentary

- |

Is The Slowdown In Health Care Inflation Here To Stay?

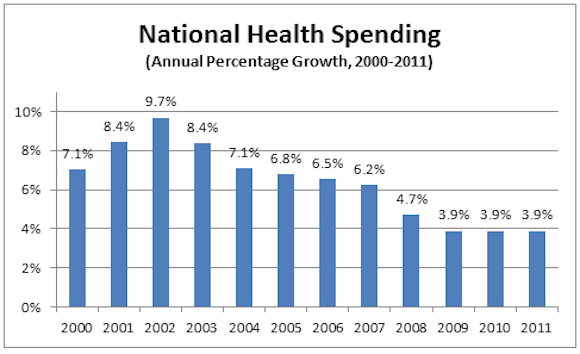

There have been plenty of hopeful signs. U.S. spending on health care rose at a 3.9% rate for the third consecutive year in 2011, about half the previous decade’s pace and the lowest since the 1960s.

A month ago, Yuval mentioned that after slowing down for seven years, the rate at which health care cost increased had stabilized at precisely 3.9 percent for each of the last three years He wrote:

Here are the figures from which the Times draws its description — the official HHS figures for year-over-year health cost inflation from 2000 to 2011:

One way to describe this trend is to say, as the Times does, that health inflation ranged from 6.2 percent to 9.7 percent between 2000 and 2007 and was at 3.9 percent from 2009 to 2011. Another is to say that a major slowdown in cost inflation began in 2003 and ended in (or at least appears to have paused since) 2009. It had not reversed as of 2011, and that’s very important. That’s what the discussion about the effects of the recession and various other factors in the Obama years is about. But it’s not about the original cause of the slowdown, which began in dramatic fashion five years before the recession.

This trend is important considering the impact it has both on the cost of health care and the cost of programs such as Obamacare, Medicare, and Medicaid. As the Wall Street Journal explains:

There have been plenty of hopeful signs. U.S. spending on health care rose at a 3.9% rate for the third consecutive year in 2011, about half the previous decade’s pace and the lowest since the 1960s.

Spending on prescription drugs actually dropped 1% in 2012, to $325.8 billion, the first decline since 1957, according to the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics.

Helped by lower drug prices, the Labor Department’s index for consumer medical costs fell a seasonally adjusted 0.1% in May, the latest data available, from the month before, the first drop in almost four decades.

According to the article, Kaiser Family Foundation published a report recently showing that three-quarters of the slowdown was due to the recession “damping demand for drugs, doctor visits and elective surgeries.” If that’s the case, then the increase in health-care spending will resume as soon as the economy recovers. Of course, it may not be as simple as that, since the slowdown actually started long before the recession hit and, in fact, the reduction stopped in 2009 and the rate has been flat ever since as Yuval mentioned above. Over at Real Clear Policy, Jordan Rau has more on this:

The second study, by Harvard economists David Cutler and Nikhil Sahni, found that national health spending between 2003 and 2012 ended up being $514 billion, or 16 percent, below the level predicted by government actuaries at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The researchers concluded that only 45 percent of the slowdown could be attributed to three factors: the recession during 2007 through 2009, a drop in coverage from private insurance and the government’s Medicare payment cuts. “The slowdown pre- and postdates the recession and shows up in populations whose medical care use is normally unaffected by economic cycles, such as the elderly,” they wrote.

They posited that the remaining 55 percent of the spending slowdown was due to “a host of structural changes—including less rapid development of imaging technology and new pharmaceuticals, increased patient cost sharing, and greater provider efficiency.” If the trends continue over the next decade, they said public-sector health care spending could be as much as $770 billion less than predicted.

Now we have to ask: What will happen to the inflation rate down the road? Will it stay at 3.9 percent, increase, or resume its slowdown? The Wall Street Journal story explains that the rate will probably rise again, in large part due to Obamacare and other factors such as democraphics and technology:

In the near term, however, the Affordable Care Act will almost certainly produce a temporary jump in spending as millions of Americans gain access to Medicaid or private insurance starting next year. That may or may not be offset by a drop in unreimbursed care.

Either way, there will still be powerful pressures driving health-care spending higher.

One is demographics: 10,000 baby boomers turn 65 every day. Per capita health costs at that age and older are $9,744 a year, compared with $2,739 for those 25 to 44, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Another big driver of health-care costs is technology. In almost every other industry, innovation generally makes things more efficient and less costly. But in health care, it often brings higher costs with little added value.

Missing from this piece, I think, is the role played by the large increase in government involvement (subsidies) in the health-care market. A recent example of this trend is the increased government intervention in student loans and its impact on tuition. In fact, it is not a coincidence that the two industries that are the most controlled by public sector’s rules, regulations, and out-right subsidies —education and health care — have seen their prices rise at higher than normal inflation. (By the way, I think the word inflation in this case is not the best way to describe what is going on. Peter Suderman explains why here.)