Given the successes of many of the recent deregulatory experiments in other countries, it seems the time has come, 35 years after airline price deregulation, to begin experimenting with more infrastructure reforms in the United States.

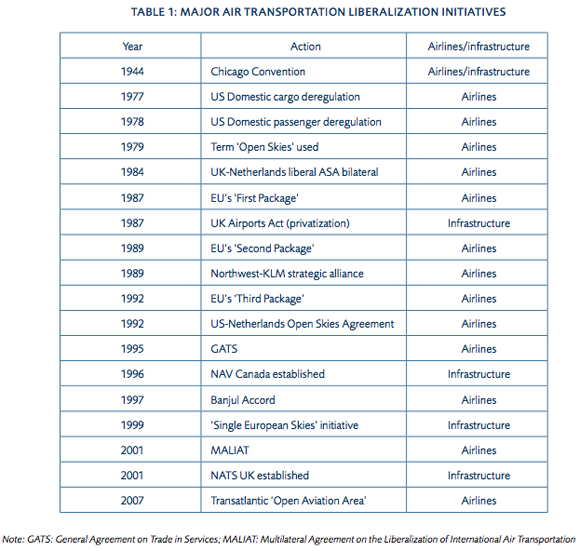

The late 1970s saw the removal of many of the economic regulations that controlled the supply of U.S. domestic freight and passenger airline services. This was followed in the 1980s with the Open Skies initiative, aimed at removing many of the impediments to the free supply of international air services. The effects of these reforms have been seen in generally lower and more diverse fares, enhanced ranges of services, and more innovation by the airlines in the way they approach their customers.[1] However, residual regulations remain, and some new ones have subsequently been added. This paper looks at how these residual regulations, and the addition of new ones, have dampened the liberalizing effects of the 1970s legislation and reduced the benefits that U.S. airline users could enjoy.

The major “deregulation” of interstate freight airline services occurred in 1977, followed by similar regulatory changes for passenger services in 1978. The legislation of the 1970s demonstrably produced net welfare gains for the American people, primarily by allowing domestic airlines to compete on price and innovations in their services. The air transportation infrastructure, however, has remained heavily regulated, and domestic airlines are largely protected from foreign competition.

Since the 1970s, there have also been measures to tighten safety, security, and environmental regulation that, in some cases, have raised questions in terms of overall value for the money.

Under the pre-1970s regime there were few direct subsidies in American domestic airline service provision, although the licensing system led to some cross-subsidization of loss-making routes from revenues from profitable ones.

Deregulation added some direct subsidies for routes involving remote communities through the Essential Air Services program, and later funds became available as part of local development initiatives. The initial funding requirements for “essential” routes proved less than expected as airlines adapted to the more competitive market, and in many cases their costs fell to the point where formerly subsidized routes became commercially viable. More recently, however, evidence suggests that some of the remaining “essential” services have become gold-plated services operative at subsidized levels that exceed the basic needs of communities.[2] Some recognition of the issue is reflected in modifications in the 2012 Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) Air Transportation Modernization and Safety Improvement Act.

The bigger issue is the lack of any significant reforms regarding air transportation infrastructure or the airports and air traffic control elements of the air transportation industry. These are controlled by municipal and federal bodies and operated with very limited application of anything approaching market principles. The U.S. air navigation system is part of the U.S. Department of Transportation and operated by the FAA. There is de facto little pricing for services; rather, revenues are generated through taxation.

Airports services, including slots and gates, are not priced according to market-based principles with "first come" a common principle used regarding take-offs and landings. In particular, fees do not reflect the prevailing congestion levels at airports and the congestion caused by different types of aircraft at different times of the day. There have been some efforts at auctioning slots with accompanying secondary markets as a form of introducing competition for the market, but this has been applied only to a few seriously congested facilities. These include New York LaGuardia and Washington Reagan National airports and applies only to some of the capacity at each. [3] The curent regulatory structure stands in stark contrast to what is happening in many other parts of the world, where there is considerable experimentation with the introduction of more market-based approaches to the supply and use of air transportation infrastructure[.[4]

Added to this, and far from fully considered here, have been a plethora of new regulations and controls relating to environmental and security matters. These topics deserve full coverage in their own right, but from a narrow economic perspective they impose additional time and disruption costs on passengers and shippers of cargo and a cost on tax-payers.[5] There may be justifications for government interventions in these areas when the underlying problems are genuine market failures, but currently little attention is given to the question of whether these policies are being implemented efficiently.

In recent times, the airline market has become increasingly global with considerable amounts of cross investments between airlines and the emergence of the three mega airline alliances: the Star Alliance, Oneworld, and SkyTeam. While the U.S. market is, to some extent, integrated into this system, the integration has been gradual and is incomplete. The result is that U.S. air travelers have not always enjoyed the full potential of globalization. In particular, investment in U.S. airlines is limited in a number of ways in terms of the extent of foreign participation and control, and competition to stimulate efficiency within the U.S. domestic market is limited to American carriers. Subsidies also remain for certain types of service and the mechanism for subsidizing is highly politicized with little evidence of any genuine cost-benefit analysis.[6]

Finally, because air transportation has become a global industry and many American policies must be set within this broader context, the United States has pursued an Open Skies stance for more than 30 years with some success in terms of encouraging the liberalization of bilateral air service agreements. However, it has done so not strictly in terms of fostering complete air transportation markets but selectively to the advantage of the nation’s airlines. In particular, the policy has focused just on the international legs of services rather than complete networks that embrace cabotage (services offered between cities within the country), and with little interest in developing efficient global markets for investment and labor. America cannot change international agreements unilaterally, but it has been instrumental in supporting some positive reforms. The ethos of U.S. initiatives has, however, often involved supporting the interests of the nation’s carriers in entering larger markets rather than in providing competitive stimuli for greater overall efficiency and maximizing benefits for airline users.

The lesson from the experiences of other countries that have liberalized their air transportation infrastructure is that the introduction of more market-oriented systems has led to unexpected results, generally more favorable to the travel- ing public. The U.S. market experienced similar unexpected benefits following the deregulatory changes in the late 1970s in the domestic market. Given the successes of many of the recent deregulatory experiments in other countries, it seems the time has come, 35 years after airline price deregulation, to begin experimenting with more infrastructure reforms in the United States.

Footnotes

1. Steven A. Morrison and Clifford Winston, The Evolution of the Airline Industry (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1995).

2. U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), “Commercial Aviation: Programs and Options for Providing Air Service to Small Communities” (report, GAO-11-733, Washington, DC, 2007).

3. D. Starkie, “Allocating Airport Slots: A Role for the Market?” Journal of Air Transport Management 4 (1998): 111–16.

4. GAO, “Air Traffic Control: Characteristics and Performance of Selected International Air Navigation Service Providers and Lessons Learned from Their Commercialization” (report, GAO-05-769, Washington, DC, 2005); and House Subcommittee on Aviation, Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, Air Traffic Control, FAA’s Modernization Efforts—Past, Present, and Future, 108th Cong., 1st sess., 2003.

5. GAO, “Airline Passenger Protections: More Data and Analysis Needed to Understand Effects of Flight Delays” (report, GAO-11-733, Washing- ton, DC, 2011).

6. GAO, “Commercial Aviation: Programs and Options for Providing Air Service to Small Communities” (report, GAO-07-793T, Washington, DC, 2007).