- | Government Spending Government Spending

- | Research Papers Research Papers

- |

The 2013 Farm Bill: Limiting Waste by Limiting Farm-Subsidy Budgets

American taxpayers currently spend more than $20 billion per year on farm subsidies, the vast majority of which flow to the largest and wealthiest farming operations. The upcoming farm bill provides Congress the opportunity to eliminate the programs that simply transfer money from less-wealthy taxpayers to wealthier farm households. The question is, will the 2013 farm bill make these politically sensitive cuts?

American taxpayers currently spend more than $20 billion per year on farm subsidies, the vast majority of which flow to the largest and wealthiest farming operations. The upcoming farm bill provides Congress the opportunity to eliminate the programs that simply transfer money from less-wealthy taxpayers to wealthier farm households. The question is, will the 2013 farm bill make these politically sensitive cuts?

In a new study from the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Vincent Smith, a professor of economics at Montana State University, analyzes current farm bill proposals by the House and Senate Agriculture Committees. The study examines how reducing farm subsidies by various levels would affect the structure of US agricultural policy. The study concludes that farm subsidies could be reduced by at least $9–10 billion per year—about 10 percent of current farm bill spending—without any measurable effect on agricultural production.

To learn more, read “The 2013 Farm Bill: Limiting Waste by Limiting Farm Subsidy Budgets.”

REDISTRIBUTING INCOME TO FARMERS

The federal government spends approximately $100 billion per year on farm bill programs. Of this, $23 billion—nearly 20 percent—goes to farm subsidy programs, including:

- $17.5 billion to the largest 15–20 percent of farm operations; of this, $14 billion is paid to the largest 10 percent.

- $2.5 billion to private agricultural insurance companies.

SUBSIDIES TO INDIVIDUAL FARMERS

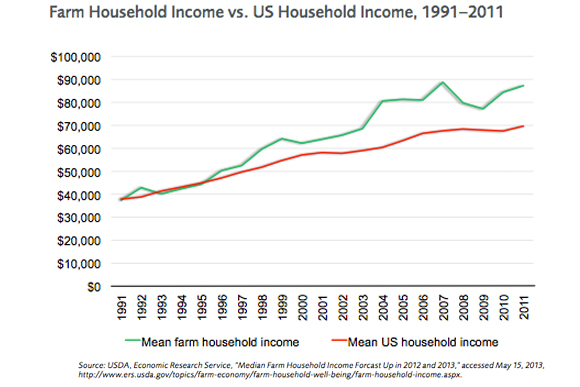

Since the 1960s, successive farms bills have funded subsidies going mainly to farm households which are much wealthier and enjoy much higher incomes than the average American household (see chart). Some subsidies to individual farmers are astonishingly large. The US General Accounting Office reported that in 2011 more than 50 farms received over $500,000 in crop insurance premiums. Many of these farms also obtained additional benefits from other subsidy programs, such as the Direct Payments program.

- Under the Direct Payments program, payments to land owners and farms are unrelated to their actual production or crops raised. In other words, farmers receive the payment even if they have a great year with crop prices near record highs, as they are now.

- Many of these farming operations are organized as partnerships that typically own multiple farms and thousands of acres of cropland. The families associated with these partnerships are much wealthier than the average American household.

THE ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL CONDITIONS OF US FARMERS

A recurring justification for these subsidies is that farmers need a safety net because farming is such a risky business. This claim is inaccurate.

- The annual failure rate for farms is 0.5 percent. The annual business failure rate, at 7 percent, is 14 times greater.

- The average debt-to-asset ratio in farming is currently 10 percent and has not exceeded 15 percent since the late 1990s. This indicates that farmers generally face very little financial risk, and as a result, even less-efficient farming operations are able to survive.

HOUSE AND SENATE AGRICULTURE COMMITTEE PROPOSALS

Both committees continue to offer farm programs and policy initiatives that provide large subsidies to these wealthy farming operations.

House Agriculture Committee

The House-passed budget for FY 2014 established a goal of cutting $3.4 billion per year from the farm bill, all from farm subsidies. While the House Agriculture Committee subsequently approved $3.8 billion in cuts in H.R. 1947, it reduced subsidies by only $1.8 billion; the remainder of the cuts came from nutrition programs.

Termination of the ACRE program. The committee would terminate the Direct Payments program and the Average Crop Revenue Election (ACRE) program, which provides payments to farmers when their per-acre revenues fall below a percent of their average revenues during the previous five years.

While this would reduce annual farm bill spending by about $5.6 billion, the committee would use $3.8 billion of those “savings” to create new programs, thus achieving only $1.8 billion in actual farm subsidy cuts.

Introduction of new programs. H.R. 1947 would spend the $3.8 billion to create 1) the Price Loss Coverage program (a new price-support program), 2) a new shallow-loss program for cotton, and 3) a new shallow-loss and heavily subsidized program (the “Supplemental Coverage Option”) designed to offset the deductible associated with the federal crop insurance program.

Senate Agriculture Committee

The Senate Agriculture Committee’s farm bill also proposes termination of the Direct Payments and ACRE programs. But in their place, the committee would create a new and potentially more expensive shallow-loss program called Average Revenue Coverage (ARC). Under ARC, farming operations would seldom receive less than 89 percent of their expected income.

THE COST OF THESE PROGRAMS

If commodity prices decline from their current near-record levels towards their long-run trends, the new programs proposed by the House and Senate Agriculture Committees could cost American taxpayers as much as $10–20 billion per year. This is two to four times more costly than the farm subsidies the committees propose to eliminate.

If these new programs are included in the 2013 farm bill, the taxpayers—not the farming operations—will become responsible for almost all of the downside price and revenue risks associated with producing corn, cotton, peanuts, wheat, rice, and many other crops. This is in addition to the risks already being shouldered by taxpayers through the heavily subsidized federal crop insurance program.

A RATIONAL APPROACH TO REFORMING AGRICULTURAL POLICY

House Republicans, Senate Democrats, and the Administration have all proposed reducing farm subsidies by more than $3 billion per year. This study considers the potential outcome of a required cut in this range, as well as potential outcomes should Congress be required to make higher levels of cuts:

1. Require $3.1–3.4 billion a year in subsidy cuts. This could be achieved by ending the $5 billion per year Direct Payments program. Actual savings would be reduced to just over $3 billion, as participation in the Direct Payments program currently serves as a disincentive to participation in the ACRE program (participants in the ACRE program are required to take a 20-percent cut in their Direct Payments check). Thus, the elimination of Direct Payments would increase participation in ACRE, raising the program’s cost from $650 million to an estimated $2 billion.

2. Require $3.5 billion a year in subsidy cuts. Requiring a cut of $3–3.5 billion from current farm subsidy programs could spur the House and Senate Agriculture Committees to end both the Direct Payments program and the ACRE program. This would result in an estimated $5.7 billion in annual savings. It would, however, then give the committees enough room to introduce either a Price Loss Coverage program or Average Revenue Coverage (ARC) shallow-loss program. As noted above, these programs could expose taxpayers to as much as $18–20 billion in new subsidy outlays if the prices for major crops, such as corn and wheat, fell from their current near-record levels.

3. Require $5 billion a year in subsidy cuts. Requiring $5 billion in cuts per year would spur the committees to eliminate both the Direct Payment and current shallow-loss ACRE programs, resulting in $5.7 billion per year in estimated savings. Unlike the previous scenario, this would not leave enough in “extra” savings to introduce a new shallow-loss or price-support program. The committees would, however, have enough money to renew a suite of livestock disaster programs (with costs of $400–500 million per year) that expired in 2011.

4. Require higher cuts in farm subsidies. Requiring higher levels of cuts, in the range of at least $9–10 billion, would force the Agriculture Committees to reform other subsidy programs in addition to eliminating the Direct Payments and ACRE programs. Such a required cut would likely force the reform of the federal crop insurance program—the largest farm subsidy, for which taxpayers subsidize 70 percent of the total costs.