- | Regulation Regulation

- | Policy Briefs Policy Briefs

- |

Bottling Up Innovation in Craft Brewing: A Review of the Current Barriers and Challenges

Instead, policymakers should focus on more direct, effective, and less problematic solutions to reduce the tangle of regulatory burdens encountered by craft brewers. Eliminating regulatory burdens for all firms would allow brewers to succeed or fail on the basis of their ability to provide the greatest value to consumers at the lowest cost to society.

“Build a better mousetrap,” the old saying goes, “and the world will beat a path to your door.” Brew a better beer, however, and regulators will tie your door shut with red tape. Startups in the craft brewing industry face formidable barriers to entry in the form of federal, state, and local regulations. These barriers limit competition and innovation, reducing consumer welfare.

While customers and new entrants are harmed, these regulations can be a privilege to incumbent firms and industries. There are various political and historical reasons for the persistence of these rules, despite the fact that they lack economic justification. Policymakers interested in economic development should eliminate regulations to help firms overcome confusing and unnecessary barriers to entry and to level the playing field between established firms and their newer, smaller rivals.

A SURVEY OF SELECTED REGULATORY BARRIERS TO ENTRY

All entrepreneurs face entry costs, regardless of the industry they seek to enter. Some of these costs are inherent to business, such as those related to developing a business plan, raising capital, and bringing the product to market. Other costs are the result of regulations that—while imposed on all firms—tend to be more burdensome for newer and smaller operators.1 A series of regulations increase the cost of developing, producing, and distributing new products in the brewing industry, including the “three-tier system” and an assortment of licensing and permitting laws.

Following the repeal of prohibition in 1934, nearly every state passed laws to mandate “three-tier” distribution systems that persist today.2 But for certain limited exceptions, these systems require that suppliers, wholesalers, and retailers (stores, restaurants, etc.) remain separate entities according to their ownership and management. Many of these state laws require that distributors be granted exclusive territories, making a particular wholesaler the exclusive source for a specific brand within a defined area. Further, as of 2003, all but four states have franchise laws that dictate how suppliers may contract with distributors and on what terms a supplier may choose to work with another distributor.3 In a recent survey of the empirical literature on laws that limit or constrain the relationship between buyers and sellers in a supply chain, economists Francine Lafontaine and Margaret Slade found that “when restraints are mandated by the government, they systematically reduce consumer welfare or at least do not improve it.” 4

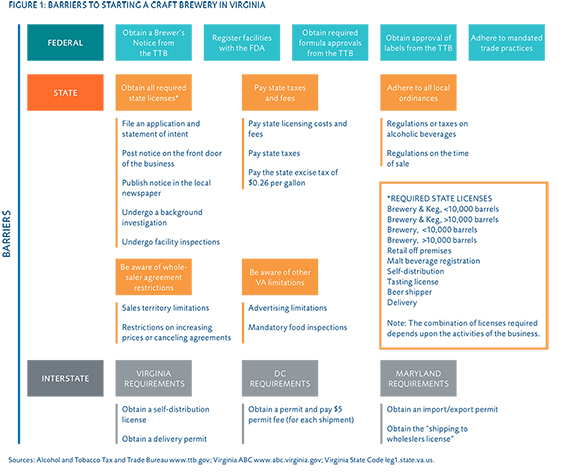

As figure 1 demonstrates, there are a number of federal and state permits and authorizations with which brewers must comply before they can bring their product to market. We find that an entrepreneur attempting to enter the brewing market in Virginia must complete at least five procedures at the federal level, five procedures at the state level, and—depending on the locality—multiple procedures at the local level.

An aspiring brewer must first obtain approval for a Brewer’s Notice from the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), a division of the US Department of the Treasury.6 This process may include background checks, field investigations, examination of equipment and premises, and legal analysis of proposed operations.7 She must then obtain a license (and potentially other authorizations) from the alcoholic beverage regulator in the state where she plans to operate her brewery and sell her beers to wholesalers.8 In Virginia, for example, this license can be refused if the state believes the brewer is “physically unable to carry on the business,” is not a person of “good moral character and repute,” fails to demonstrate the “financial responsibility sufficient to meet the requirements of the business,” or is unable to “speak, understand, read and write the English language in a reasonably satisfactory manner.” 9 The state may even refuse to grant a license if it feels that there are enough brewers in the locality and an additional brewer would be “detrimental to the interest, morals, safety or welfare of the public.” 10

Before her first bottle can be sold, the brewer must also obtain approval for her beer label from the TTB and register that same label in states where she plans to sell it.11 Depending on her ingredients and brewing methods, she may also need approval from the TTB for her formula as well.12 Once she is in business, the brewer must ensure that her ingredients and brewing methods comply with regulations enforced by TTB, the Food and Drug Administration, and—in the case of organic beers—the US Department of Agriculture.13 In addition, how the brewer, wholesaler, and retailer market beer is subject to federal and state regulation.

Throughout this process, the brewer will face wait times and fees that add to the cost of entering and competing in the market. To obtain her Brewer’s Notice from the TTB, she must wait approximately 100 days.14 To receive approval for her formula, she could wait an additional 60 days.15 And to receive approval for her label, she could wait another 17 days.16 With regard to fees, the state brewery license will cost $350 if she brews fewer than 500 barrels of beer in one year, $2,150 if she brews between 501 and 10,000 barrels in one year, or $4,300 if she brews more than 10,001 barrels.17

In aggregate, the number of regulatory procedures that we identify (12), the wait times to complete many of these procedures (in excess of 100 days), and the associated costs (e.g., $2,150 for a single license) represent formidable barriers to entry. All of these barriers are in addition to the standard regulatory hurdles that all small businesses must surmount (zoning ordinances, incorporation rules, and tax compliance costs). This means that starting a microbrewery in the state of Virginia requires as many procedures as starting a small business in China or Venezuela, countries notorious for their excessive barriers to entry.18