- | Academic & Student Programs Academic & Student Programs

- | Corporate Welfare Corporate Welfare

- | Policy Briefs Policy Briefs

- |

Certificate-of-Need Laws and North Carolina: Rural Health Care, Medical Imaging, and Access

Certificate-of-need (CON) programs are state laws that require government permission for healthcare providers to open or expand a practice or to invest in certain devices or technology. These programs have been justified on the basis of achieving several public policy goals, including controlling costs and increasing access to healthcare services in rural areas. Little work has been done, however, to measure what effects CON programs have on access and distribution of healthcare services. Two recent studies that examined the relationship between a state’s CON program and access to care found that these laws failed to achieve their stated goals.

Certificate-of-need (CON) programs are state laws that require government permission for healthcare providers to open or expand a practice or to invest in certain devices or technology. These programs have been justified on the basis of achieving several public policy goals, including controlling costs and increasing access to healthcare services in rural areas. Little work has been done, however, to measure what effects CON programs have on access and distribution of healthcare services. Two recent studies that examined the relationship between a state’s CON program and access to care found that these laws failed to achieve their stated goals.

We highlight the results from these two studies and examine the effects that CON laws have on the distribution of hospitals and nonhospital providers, as well as the availability of medical imaging technology. Specifically, 36 states continue to enforce CON programs. Twenty-six of those states also regulate the entry and expansion of ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs), which are typically facilities that provide certain outpatient surgeries and diagnostic procedures. Additionally, 21 states restrict the acquisition of imaging equipment (i.e., MRI, CT, and PET scans).

What effect do these regulations have on patients’ ability to receive care in North Carolina?

CON laws protect established health care providers from competition, and this protection negatively affects North Carolinians. The data show that the presence of a CON program in North Carolina is associated with:

- Fewer rural hospitals and fewer hospitals overall;

- Fewer rural ASCs and fewer ASCs overall;

- Less availability of imaging services in CON states relative to non-CON states;

- Increases in the number of patients traveling out of state to obtain medical imaging relative to non-CON states.

The following charts apply these findings to North Carolina, illustrating the empirical evidence regarding its CON program’s effect on rural health care, as well as its CON program’s effect on medical imaging services. The main finding is that CON laws create a formidable barrier to entry that restricts the available options for those seeking quality care in North Carolina. Moreover, for those policymakers looking to expand access to quality health care, repealing CON laws may be an easy place to start.

The Impact of CON on Rural Health Care

CON laws were supposed to protect access to health care, particularly in rural areas, by limiting how providers could enter and compete in particular markets. States justified regulating the entry and expansion of ASCs—which provide certain outpatient surgeries and procedures—based on the belief that, if not regulated, ASCs would choose to treat more profitable, less complicated, well-insured patients and leave hospitals to treat the less profitable, more complicated, and uninsured patients. The fear was that this disparity would put those hospitals operating with slim profit margins, especially in rural areas, in a precarious financial position and force some to close. Subsequent hospital closures would then leave rural populations with reduced access to important medical services.

In reality, however, CON laws are associated with fewer overall hospitals and ASCs, as well as fewer rural hospitals and ASCs.

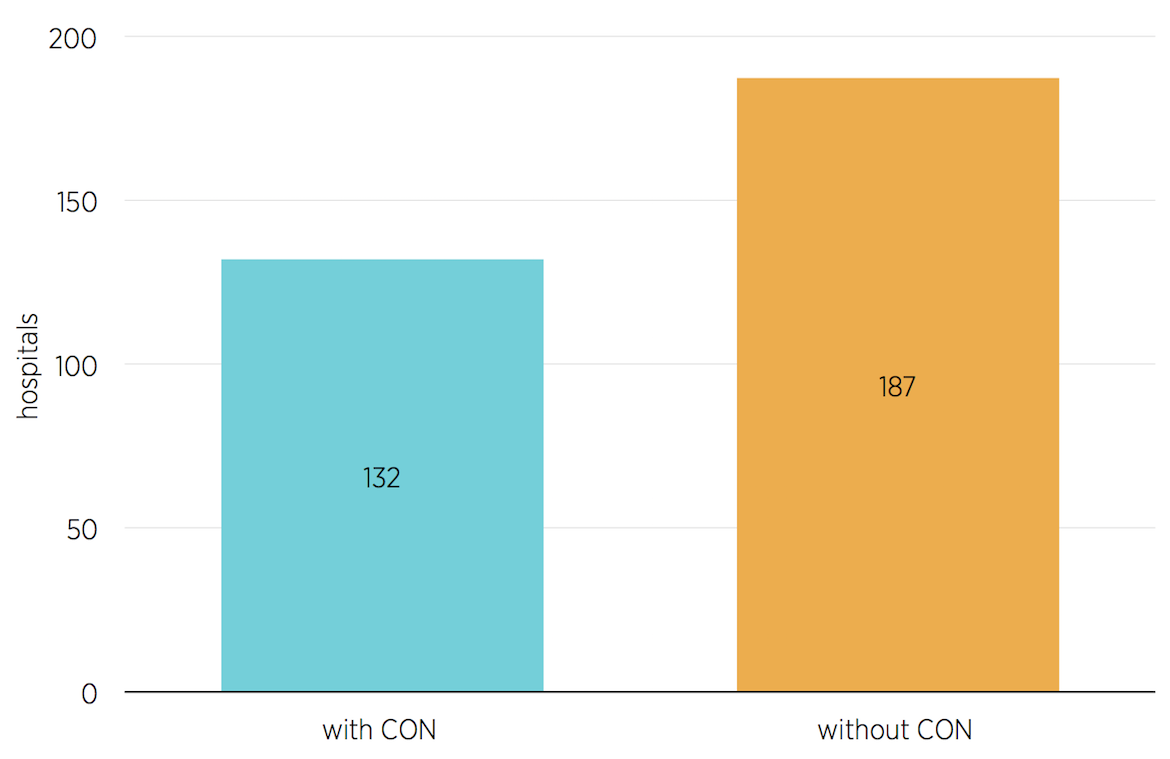

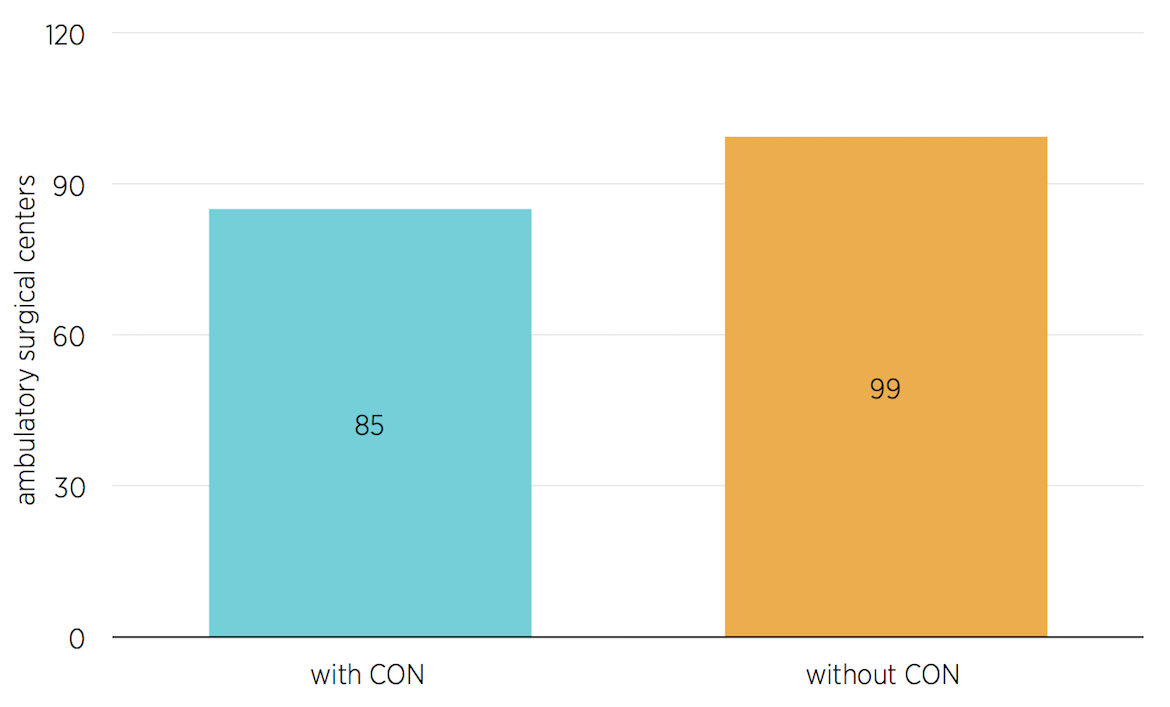

The data show that the presence of a CON program is associated with 30 percent fewer total hospitals per capita. Moreover, the presence of an ASC-specific CON requirement is associated with 14 percent fewer total ASCs per capita. Figures 1 and 2 show what this might mean for North Carolina. In 2011, North Carolina had 132 hospitals and 85 ambulatory surgical centers. These charts show that the presence of a CON program in North Carolina means fewer new entrants, fewer providers, and lower overall access to care across North Carolina relative to non-CON states.

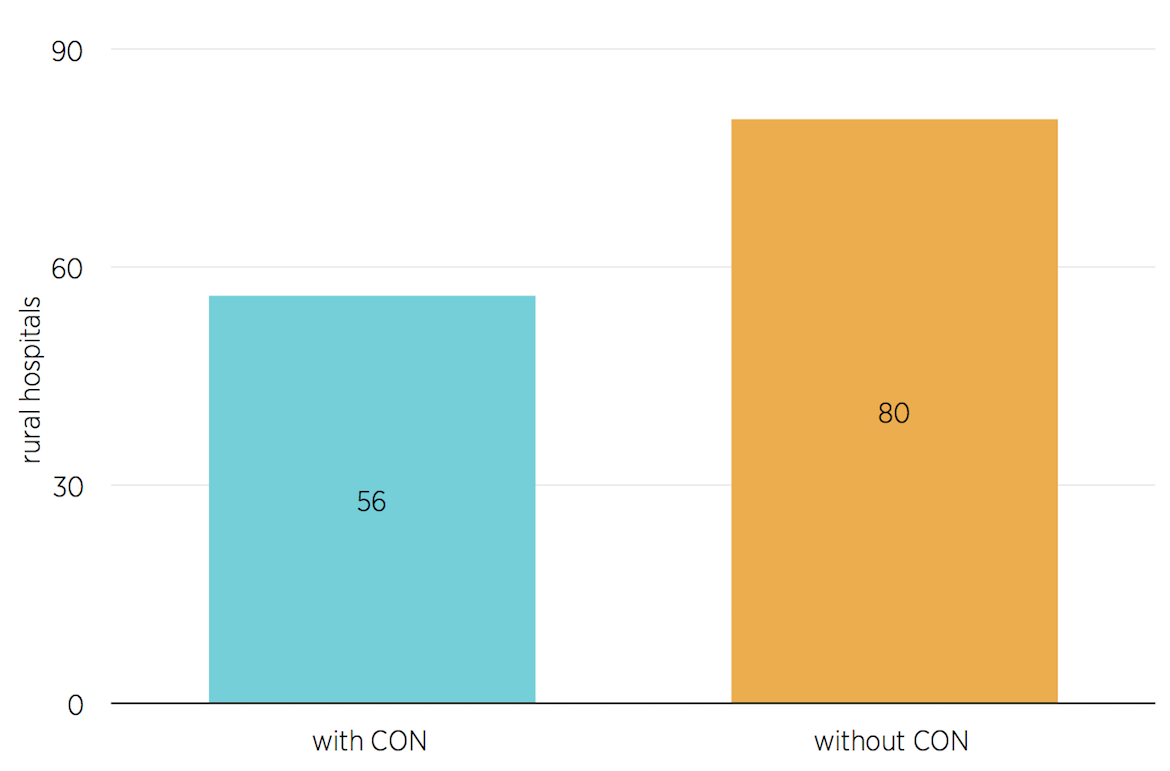

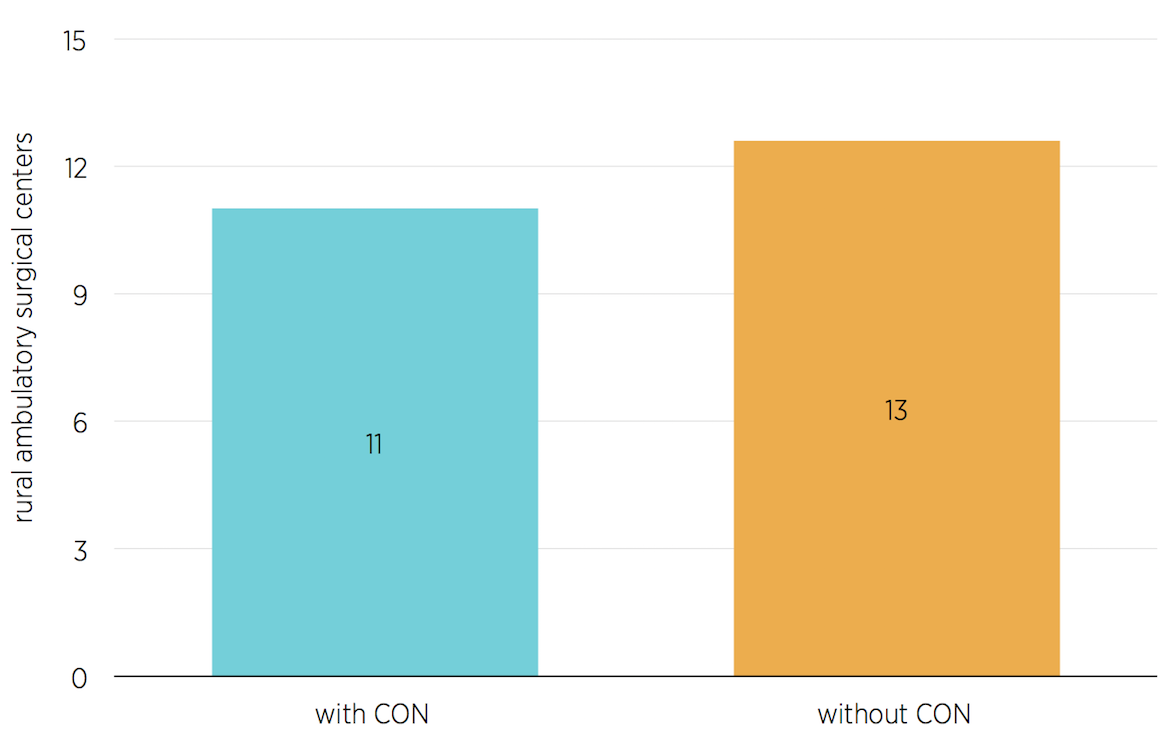

Also, in direct contradiction to the stated justifications for these programs, the data show that CON laws are associated with fewer hospitals and ASCs in rural communities. Specifically, the presence of a CON program is associated with 30 percent fewer rural hospitals per 100,000 rural population, and the presence of an ASC-specific CON requirement is associated with 13 percent fewer rural ASCs per 100,000 rural population. In 2011, North Carolina had 56 rural hospitals and 11 rural ASCs. Figures 3 and 4 show that, while intended to protect access to care in rural communities, the presence of a CON program in North Carolina is associated with fewer providers.

The Impact of CON on Medical Imaging Services

CON requirements also effectively protect established hospitals from nonhospital providers, including independently practicing physicians, group practices, and others. The result of this protection is fewer overall imaging services in CON states relative to non-CON states.

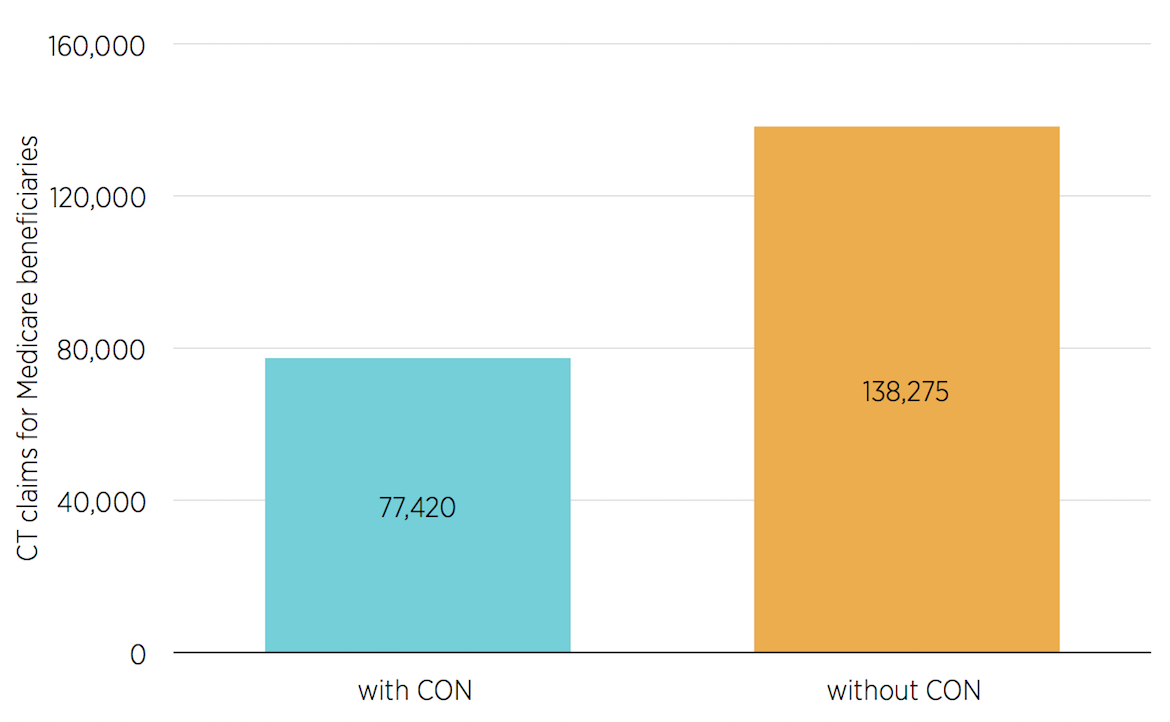

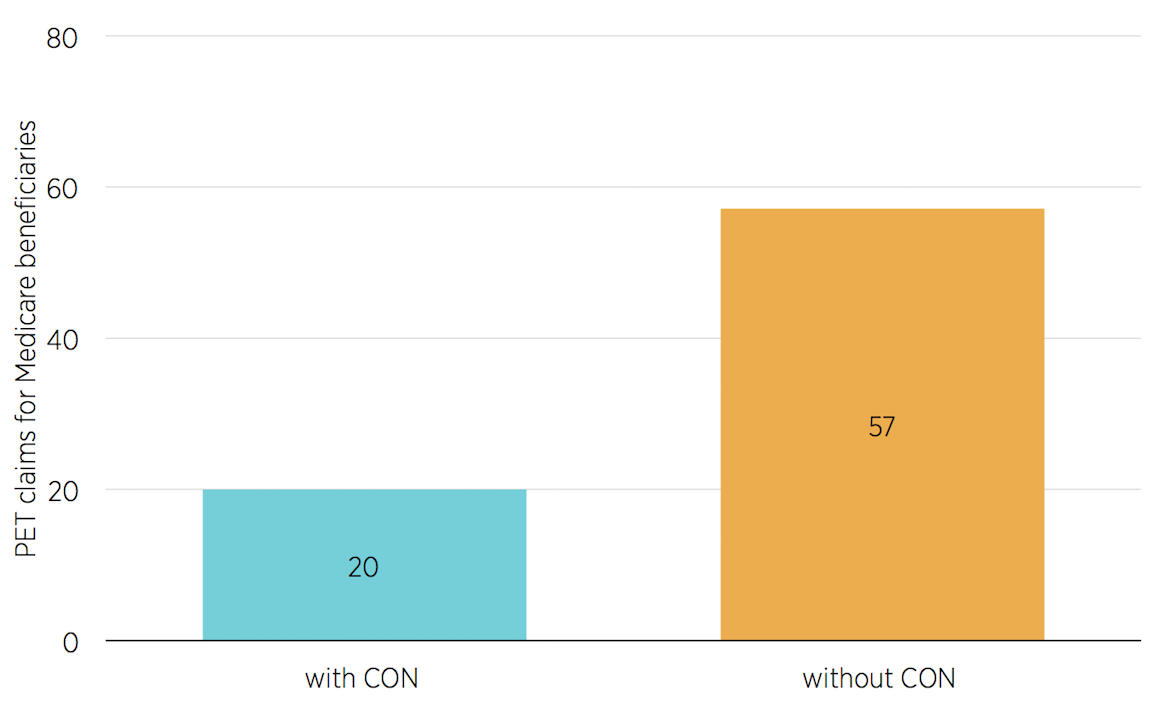

Specifically, the data show that the presence of CON is associated with a 34 percent decrease in MRI scans, a 44 percent decrease in CT scans, and a 65 percent decrease in PET scans. What does this mean for North Carolina? Using Medicare claims data, we can make some general estimates. Figure 5 shows that in 2013, North Carolina had almost 97,000 MRI claims, which means that there were an estimated 51,000 fewer MRI scans completed within the state given the presence of a CON requirement on MRI scans. Figures 6 and 7 show that for CT and PET, the presence of a CON requirement is associated with 61,000 fewer CT scans and 37 fewer PET scans.

An additional and no less important factor in understanding a CON program’s effects on a state’s healthcare market is that the presence of a CON program has no statistically significant effect on imaging services provided by hospitals. This provides evidence that CON laws do protect hospitals from nonhospital competition, but they are also associated with a significant reduction in the number of imaging services provided across the state.

The Impact of CON on Access to Care

CON laws reduce the options available to patients across North Carolina. This is pushing patients to seek health care in other states, such as Georgia, South Carolina, Tennessee, or even Florida. These states have chosen not to regulate medical imagining as North Carolina does (Georgia does not regulate MRI or CT services, South Carolina and Tennessee do not regulate CT services, and Florida does not regulate MRI, CT, or PET services).

For example, the presence of a CON program is associated with 3.93 percent more MRI scans, 3.52 percent more CT scans, and 8.13 percent more PET scans occurring out of state relative to states without CON. For North Carolina, this means that approximately 9,000 MRI scans, 19,000 CT scans, and 500 PET scans are happening outside of North Carolina annually.

Conclusion

CON laws decrease the supply and availability of healthcare services by limiting entry and competition. For North Carolina specifically, the data show that CON programs are associated with decreases in access and availability. This means there are fewer hospitals and ASCs across the state and in rural communities, imaging services are less available across the state, and an increasing number of patients are choosing to seek care outside of North Carolina.

For policymakers in North Carolina, repealing CON laws would open the local healthcare market for new providers, allow for increased competition, and ultimately offer more options for quality care for North Carolinians.

Figure 1. The Effect of CON on Hospitals in North Carolina

Source: Authors’ calculations based on findings in Thomas Stratmann and Christopher Koopman, “Entry Regulation and Rural Health Care: Certificate-of-Need Laws, Ambulatory Surgical Centers, and Community Hospitals” (Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, February 2016).

Figure 2. The Effect of CON on Ambulatory Surgical Centers in North Carolina

Source: Authors’ calculations based on findings in Stratmann and Koopman, “Entry Regulation and Rural Health Care.”

Figure 3. The Effect of CON on Rural Hospitals in North Carolina

Source: Authors’ calculations based on findings in Stratmann and Koopman, “Entry Regulation and Rural Health Care.”

Figure 4. The Effect of CON on Rural Ambulatory Surgical Centers in North Carolina

Source: Authors’ calculations based on findings in Stratmann and Koopman, “Entry Regulation and Rural Health Care.”

Figure 5. The Effect of CON on Nonhospital MRI Claims for Medicare Beneficiaries in North Carolina

Source: Authors’ calculations based on findings in Thomas Stratmann and Matthew C. Baker, “Are Certificate-of-Need Laws Barriers to Entry? How they Affect Access to MRI, CT, and PET Scans” (Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, January 2016).

Figure 6. The Effect of CON on Nonhospital CT Claims for Medicare Beneficiaries in North Carolina

Source: Authors’ calculations based on findings in Stratmann and Baker, “Are Certificate-of-Need Laws Barriers to Entry?”

Figure 7. The Effect of CON on Nonhospital PET Claims for Medicare Beneficiaries in North Carolina

Source: Authors’ calculations based on findings in Stratmann and Baker, “Are Certificate-of-Need Laws Barriers to Entry?”

To speak with a scholar or learn more on this topic, visit our contact page.