- | Government Spending Government Spending

- | Data Visualizations Data Visualizations

- |

Corporations Are Trying to Escape from High US Taxes

Pfizer Inc. recently became the largest US firm to move to a lower-tax jurisdiction by combining with a foreign competitor. In this so-called “inversion,” Pfizer will merge with Allergan PLC, and the new headquarters will be located in Ireland. Inversions are a symptom the United States’ broken, outdated, and uncompetitive corporate tax system. The United States has the single highest corporate tax rate in the developed world—the US combined corporate tax rate is 39.1 percent. The chart below shows that US peer nations have systematically lowered their high corporate tax rates, while the United States’ rate has remained unchanged.

Pfizer Inc. recently became the largest US firm to move to a lower-tax jurisdiction by combining with a foreign competitor. In this so-called “inversion,” Pfizer will merge with Allergan PLC, and the new headquarters will be located in Ireland. Inversions are a symptom the United States’ broken, outdated, and uncompetitive corporate tax system.

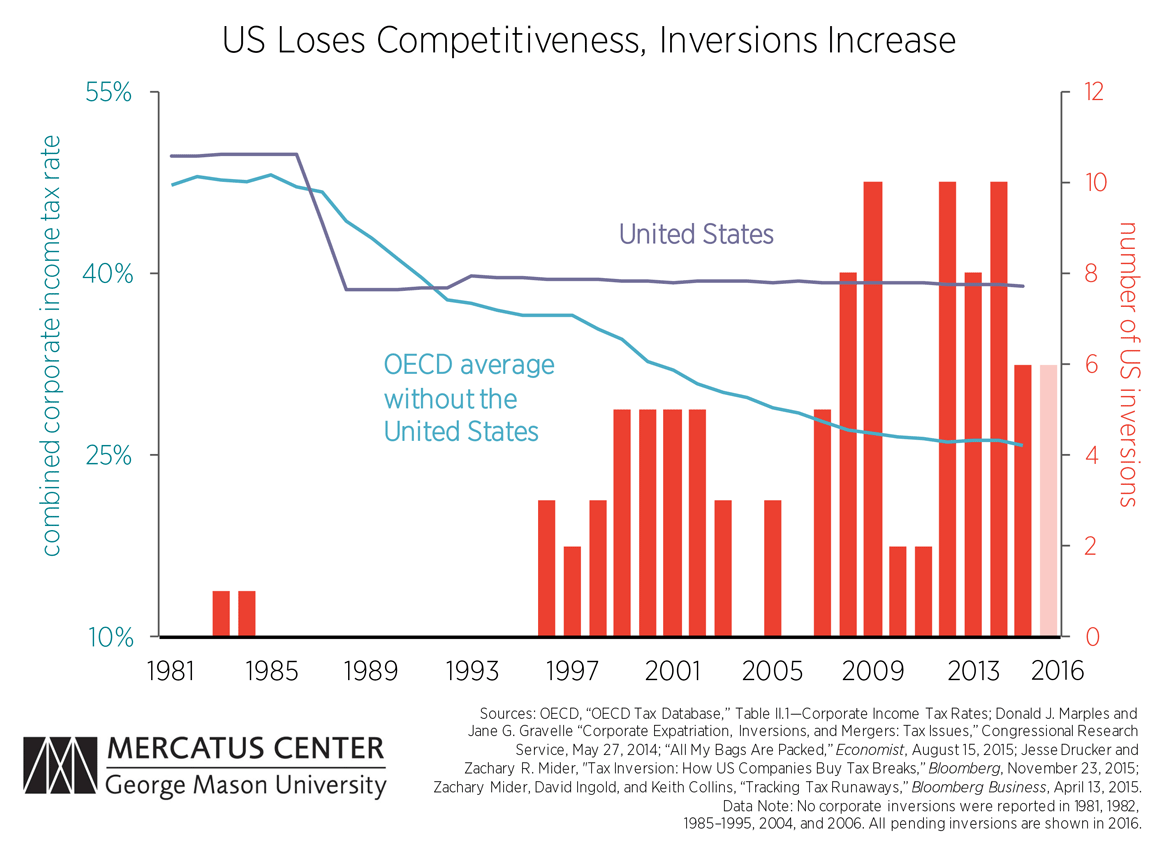

The United States has the single highest corporate tax rate in the developed world—the US combined corporate tax rate is 39.1 percent. The chart below shows that US peer nations have systematically lowered their high corporate tax rates, while the United States’ rate has remained unchanged.

As our peer nations’ tax rates become more attractive, the chart shows a simultaneous rise in US corporations moving abroad to lower-tax countries.

In addition to high rates, the United States is one of just six countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development that still uses 1960s-era tax rules that attempt to tax the worldwide income of its domestic corporations. Worldwide tax systems tax all income of domestically headquartered businesses, including income earned by subsidiaries operating abroad. Firms are allowed to defer paying taxes on “active” foreign income until that income is brought back, or repatriated, into the United States.

The United States should abandon the worldwide system in favor of a system of territorial taxation. Territorial taxation only taxes income earned within the country’s borders. Taxing income where it is earned levels the playing field, so that each firm’s operations in a particular jurisdiction are taxed at the same rate, regardless of the location of corporate ownership.

A territorial system could encourage economic growth, allowing corporate profits to flow to their highest-value use. The current US system of worldwide taxation locks approximately $2 trillion of corporate profits out of the US economy. This system forces firms to either reinvest those profits overseas or hold those profits abroad idly waiting for a lower US corporate tax rate to bring them back to the United States. Under a territorial system, corporate profits could be reinvested in American infrastructure, factories, and research and development—or paid out to American investors and retirees as dividends.

A new Mercatus on Policy paper discusses the Treasury Department’s misguided attempts to stop corporate inversions through regulatory fiat. A preferable policy alternative would be for US policymakers to lower the top marginal federal corporate income tax rate to be no higher than the OECD average of 25 percent. The paper also discusses other ways to achieve truly competitive reform.