- | Regulation Regulation

- | Data Visualizations Data Visualizations

- |

The Costs of Regulation and Spending: Is Congress Driving, or Are We on “Autopilot”?

Taxes and the costs of complying with regulation are two of the larger and more noticeable ways that private individuals pay for government services. Yet it may surprise you to learn that a significant portion of the federal government’s expenditures and indirect costs to the economy occur each year on “autopilot” without any action by the current Congress. These autopilot costs are the result of past legislation, interest payments, and rules created by government agencies, all of which bypass the annual appropriations process that exists to ensure the accountability of our elected officials.

Taxes and the costs of complying with regulation are two of the larger and more noticeable ways that private individuals pay for government services. Yet it may surprise you to learn that a significant portion of the federal government’s expenditures and indirect costs to the economy occur each year on “autopilot” without any action by the current Congress. These autopilot costs are the result of past legislation, interest payments, and rules created by government agencies, all of which bypass the annual appropriations process that exists to ensure the accountability of our elected officials.

Some federal government costs are included in the yearly budget. For example, discretionary expenditures—those appropriated by annual congressional vote—are budgeted at $1.15 trillion for fiscal year (FY) 2015. According to a yearly report by Susan Dudley of George Washington University and Melinda Warren of Washington University in St. Louis, $62 billion of that $1.15 trillion will flow to regulatory agencies. While this is a substantial figure, it is rather small in terms of overall government spending. The sum of regulatory costs to the economy, however, extends far beyond the salaries and spending at the agencies themselves.

The off-budget, or autopilot, costs of regulations are much more difficult to calculate than those plainly stated in the federal budget. These are the costs of complying with regulations that are faced by consumers and producers, and they are paid through higher prices, lower wages, and reduced innovation. An oft-cited report by Clyde Wayne Crews Jr. of the Competitive Enterprise Institute estimates that these off-budget costs will be approximately $1.88 trillion in 2015. Other organizations such as the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) offer estimates that help illustrate the wide range and uncertainty in this calculation.

NAM estimates these costs were $2.03 trillion in 2012, while OMB calculates that the range of annual costs from 2001 to 2013 was $74.3 to $110.5 billion (all amounts adjusted to 2015 dollars by the authors). However, the OMB estimation only includes the costs of 116 of the 569 major regulations (those with an impact of $100 million in at least one year) and none of the 36,453 regulations that do not qualify as major during this period. They acknowledge that because of this exclusion, “the total benefits and costs of all Federal rules now in effect are likely to be significantly larger than the sum of the benefits and costs reported.” Yet even the low range of the OMB estimates, when compared to the figure from Dudley and Warren, shows that only 45 percent of the costs of regulations are reflected in the annual appropriations by Congress ($62 billion out of $136.3 billion). The higher-range estimates from Crews and NAM indicate that this figure may be as low as 3 percent.

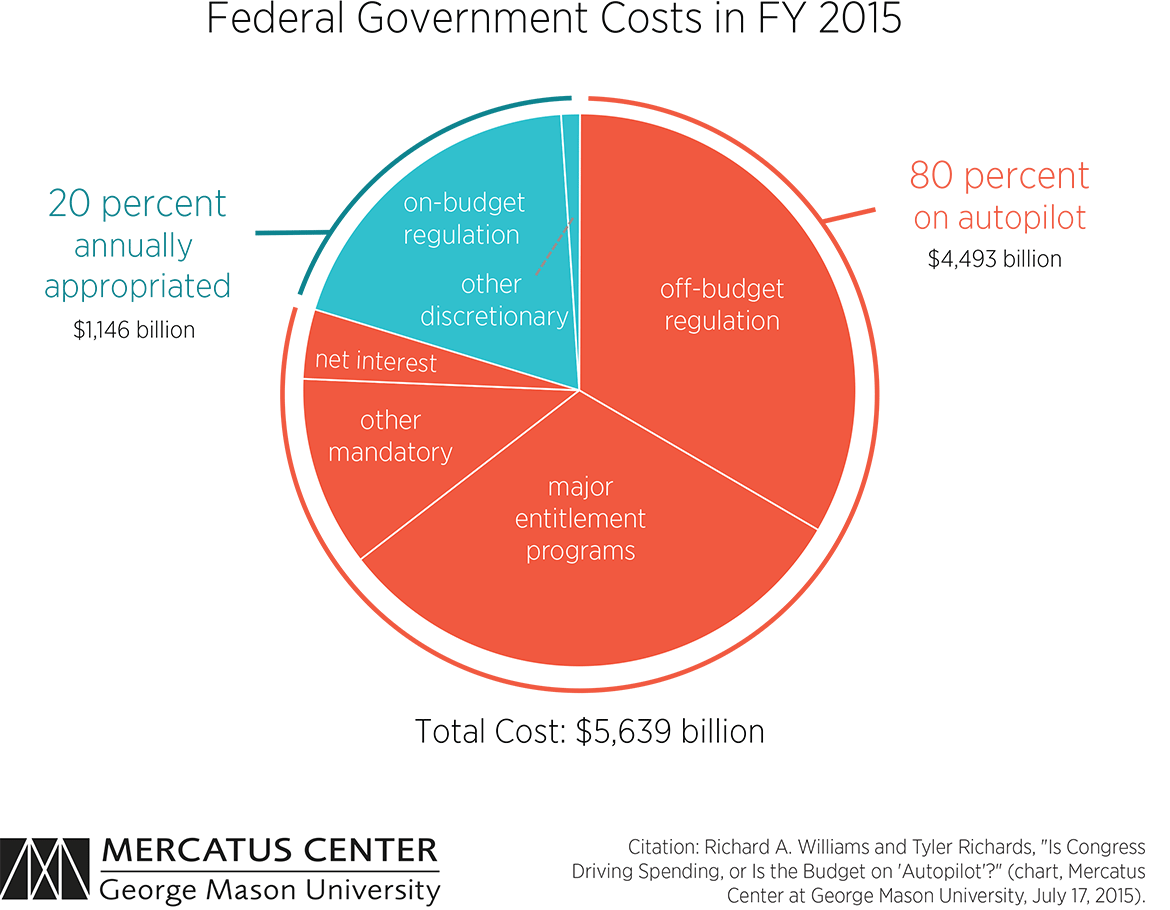

To get a full picture of the costs of government, we must also take into account the expenditures that are on the budget but are not appropriated each year by congressional votes. The three largest entitlement programs, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, are estimated at $1.75 trillion for the year. These programs, along with another $628 billion in other mandatory spending and $229 billion in net interest, account for the remainder of the autopilot costs. Combining the estimations of off-budget regulation costs and the numbers from the federal budget, we can produce estimations of the total cost of the federal government in 2015.

Then we can separate the costs which are appropriated by Congress as part of the annual budget process from those which are not to see how much is on autopilot. The appropriated costs are the discretionary expenditures, including on-budget regulation. Those remaining—off-budget regulation, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, other mandatory programs, and net interest—give us the total autopilot costs. Using the Crews estimate, the data reveal that the current Congress is voting on just 20 percent of the amount that we pay for their services, leaving 80 percent as autopilot costs (see chart). But even using the lower-bound estimate of $74.3 billion for off-budget regulation would only decrease the autopilot costs to 70 percent of the total.

This recurring process is not inescapable. Our colleagues Jason Fichtner and Patrick McLaughlin have proposed legislative impact accounting, a method of more accurately estimating costs and including them in the annual budget process. This method would:

Incorporate economic analyses of legislation and regulation into the budget process in two ways: First, when new legislation is proposed, an independent office—perhaps the Congressional Budget Office—would produce an estimate of the economic costs the legislation would create. Importantly, a legislative impact assessment would attempt to consider economic costs of proposed legislation, not just budgetary outlays. . . . Second, legislative impact accounting would require retrospective analyses of the economic effects of legislation, starting five years after the legislation passed. The idea is to learn what the real effects have been, and to then update the original estimates produced in the first stage. This would effectively create a much-needed feedback loop that communicates information about the economic effects of legislation back to Congress.

Such a process could help inform Congress and the public about the hidden costs that accompany legislation and regulation—and help incorporate this information into the annual appropriations process.

Indeed, any effort to account for these autopilot costs would help promote transparency and accountability within the federal government.