- | Academic & Student Programs Academic & Student Programs

- | Corporate Welfare Corporate Welfare

- | Working Papers Working Papers

- |

Do Certificate-of-Need Laws Increase Indigent Care?

If state CON regulations grant medical providers market power, there should be evidence of hospital capacity restrictions such as fewer hospital beds. Capacity restrictions would allow providers to raise prices, giving them excess profits to spend on indigent care. However, without market power, providers are unlikely to have additional money to spend on indigent care, though such spending may be mandated in some CON regulations.

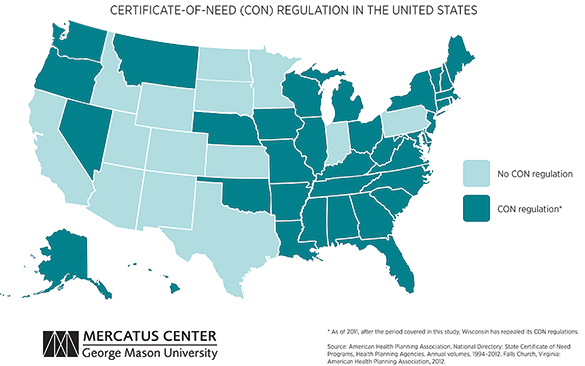

Originally introduced to the United States in 1964 by New York, certificate-of-need (CON) regulations seek to contain health care costs by limiting overinvestment in facilities and equipment. CON regulations require a medical provider, such as a hospital, nursing home, or ambulatory surgical center, to demonstrate a clear public need before providing a new service or facility. An intended result of this government restriction on the marketplace is that providers will use the profits gained from decreased competition to subsidize care for indigent people by covering losses on services that cannot be paid for by the patient or by government.

In a new empirical study of CON regulation and indigent care, economists Thomas Stratmann and Jacob W. Russ find no evidence that CON regulations increase indigent care, but they do find evidence that the regulations limit the provision of medical services. Consequently, the price of medical care is likely higher under CON regulations, while the poorest Americans see no increase in the availability of care.

DATA AND EMPIRICAL STRATEGY

The study uses state-level measures of indigent care and compiles a comprehensive database on state CON regulations from three sources:

- The Healthcare Cost Report Information System provides the direct measure of indigent care: uncompensated care. For example, the number of beds from reporting hospitals is used to standardize uncompensated care on a per-bed basis.

- Two American Hospital Association sources (Hospital Statistics 2013 and Health Forum’s Medicaid statistics) provide an indirect measure of indigent care by looking at the ratios of Medicaid patient days to total patient days and Medicaid admissions to total patient discharges.

- CON regulation data come from the American Health Planning Association’s annual survey of state CON programs. From this data, the authors have compiled the most comprehensive dataset on CON regulations to date.

The study uses several empirical strategies when analyzing the data:

- It takes into account the fact that although a state may have a CON regulation agency, the agency may or may not regulate a particular service or type of equipment—states have different approaches to CON regulation.

- It controls for demographic information from the Census Bureau, as well as unemployment-rate data and real income, by indexing each year to inflation using 2011 as a base year.

- It uses the percentage of adults with diabetes as an additional control variable to capture poor health outcomes that may not be captured by other control variables.

RESULTS

If state CON regulations grant medical providers market power, there should be evidence of hospital capacity restrictions such as fewer hospital beds. Capacity restrictions would allow providers to raise prices, giving them excess profits to spend on indigent care. However, without market power, providers are unlikely to have additional money to spend on indigent care, though such spending may be mandated in some CON regulations.

Hospital Capacity

CON regulations do correlate with fewer hospital beds and with other measures of restricted capacity.

- On average, there are 362 hospital beds per 100,000 people in the United States.

- The presence of a state CON regulation program is associated with 99 fewer hospital beds per 100,000 people. Not every state regulates acute hospital beds, however. In states that do, there are on average about 131 fewer beds per 100,000 people.

- On average, there are 4.7 fewer hospital beds per 100,000 people for each additional service a state regulates.

- CON regulations reduce the number of hospitals with MRI machines by one to two hospitals per 500,000 people. States that regulate MRI machines have, on average, 2.5 fewer hospitals with MRI machines.

Indigent Care

Uncompensated care is given by a medical provider when the patient is unable to pay the provider. For 2007–2011, the average annual level of uncompensated care in the United States was about $100,000 per hospital bed.

- A CON regulation that requires charitable care by the provider does not statistically correlate with an increase in uncompensated care.

- Medicaid patients may have higher patient costs and lower reimbursement rates. There is little evidence of CON regulations providing a cross-subsidy for Medicaid patients.

- An increase in uncompensated care may not represent a true increase in indigent care. If regulators focus on uncompensated care to measure the provision of medical services to indigent people, they may incentivize hospitals to provide unnecessary, billable services to the same number of patients, increasing costs but not the level of care for indigent people.

CONCLUSION

- CON regulations that regulate certain medical services in a state do not seem to help finance a subsidy to the medically indigent. The data collected does not allow a conclusion about whether the lack of cross-subsidization is due to an insufficient increase in hospital profits or a state’s failure to enforce indigent care provisions.

- CON regulations are effective at restricting the supply of regulated medical services, and this does not correlate with an increase in the level of indigent care.

- With services such as the number of beds and MRI machines restricted statewide, prices are likely higher for most patients, without the desired increase in indigent care.