- | Academic & Student Programs Academic & Student Programs

- | Monetary Policy Monetary Policy

- | Policy Briefs Policy Briefs

- |

Does Government Spending Affect Economic Growth?

Government spending, even in a time of crisis, is not an automatic boon for an economy's growth. A body of empirical evidence shows that, in practice, government outlays designed to stimulate the economy may fall short of that goal.

In response to the financial crisis and its impact on the economy, the federal government has increased government spending markedly in order to stimulate economic growth. With billions of taxpayer dollars appropriated toward this effort, policy makers should examine whether federal spending actually promotes economic growth. Although the studies are not all consistent, historical evidence suggests an undesirable, long-run effect from government spending: it crowds out private-sector spending and uses money in unproductive ways.

Policy makers should use the best literature available to analyze government spending designed to spur growth for the likelihood of achieving that effect. Where the assumptions or data are uncertain, the analysis should fully explore the potential consequences of different assumptions or different potential values for the uncertain data.

TRADITIONAL GROWTH RATIONALES

Proponents of government spending claim that it provides public goods that markets generally do not, such as military defense, enforcement of contracts, and police services.1 Standard economic theory holds that individuals have little incentive to provide these types of goods because others tend to use them without paying.

John Maynard Keynes, one of the most significant economists of the 20th century, advocated government spending, even if government has to run a deficit to conduct such spending.2 He hypothesized that when the economy is in a downturn and unemployment of labor and capital is high, governments can spend money to create jobs and employ capital that have been unemployed or underutilized. Keynes's theory has been one of the implicit rationales for the current federal stimulus spending: it is needed to boost economic output and promote growth.3

These views of spending assume that government knows exactly which goods and services are underutilized, which public goods will be value added, and where to redirect resources. However, there is no information source that allows the government to know where goods and services can be most productively employed.4 Federal spending is less likely to stimulate growth when it cannot accurately target the projects where it would be most productive.

POLITICS DRIVES GOVERNMENT SPENDING

In addition to this information problem, the political process itself can stunt economic growth. For example, Professor Emeritus of Law at George Mason University Gordon Tullock suggests that politicians and bureaucrats try to gain control of as much of the economy as possible.5 Moreover, demand for government resources by the private sector leads to misallocation of resources through "rent seeking"—the process by which industries and individuals lobby the government for money. Rather than spend money where it is most needed, legislators instead allocate money to favored groups.6 Though this may yield a high political return for incumbents seeking reelection, this process does not favor economic growth.

The data support the theory. A 1974 paper by Stanford's Gavin Wright found that political attempts to maximize votes explained between 59 and 80 percent of the difference in per capita federal spending to the states during the Great Depression.7 Ultimately, spending under the Democratic Congress and the president was much more concentrated in Western states, where elections were much tighter than in the Democratically controlled South. Wright's analysis indicates that instead of allocating spending based purely on economic need during a crisis, the party in power may distribute funding based on the prospect of political returns.

THE CONSEQUENCES OF UNPRODUCTIVE SPENDING AND THE MULTIPLIER EFFECT

Proponents of government spending often point to the fiscal multiplier as a way that spending can fuel growth. The multiplier is a factor by which some measure of economy-wide output (such as GDP) increases in response to a given amount of government spending. According to the multiplier theory, an initial burst of government spending trickles through the economy and is re-spent over and over again, thus growing the economy. A multiplier of 1.0 implies that if government created a project that hired 100 people, it would put exactly 100 (100 x 1.0) people into the workforce. A multiplier larger than 1 implies more employment, and a number smaller than 1 implies a net job loss.

In its 2009 assessment of the job effects of the stimulus plan, the incoming Obama administration used a multiplier estimate of approximately 1.5 for government spending for most quarters. This would mean that for every dollar of government stimulus spending, GDP would increase by one and a half dollars.8 In practice, however, unproductive government spending is likely to have a smaller multiplier effect. In a September 2009 National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) paper, Harvard economists Robert Barro and Charles Redlick estimated that the multiplier from government defense spending reaches 1.0 at high levels of unemployment but is less than 1.0 at lower unemployment rates. Non-defense spending may have an even smaller multiplier effect.9

Another recent study corroborates this finding. NBER economist Valerie A. Ramey estimates a spending multiplier range from 0.6 to 1.1.10 Barro and Ramey's multiplier figures, far lower than the Obama administration estimates, indicate that government spending may actually decrease economic growth, possibly due to inefficient use of money.

CROWDING OUT PRIVATE SPENDING AND EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

Taxes finance government spending; therefore, an increase in government spending increases the tax burden on citizens—either now or in the future—which leads to a reduction in private spending and investment. This effect is known as "crowding out."

In addition to crowding out private spending, government outlays may also crowd out interest-sensitive investment.11 Government spending reduces savings in the economy, thus increasing interest rates. This can lead to less investment in areas such as home building and productive capacity, which includes the facilities and infrastructure used to contribute to the economy's output.

An NBER paper that analyzes a panel of OECD countries found that government spending also has a strong negative correlation with business investment.12 Conversely, when governments cut spending, there is a surge in private investment. Robert Barro discusses some of the major papers on this topic that find a negative correlation between government spending and GDP growth.13 Additionally, in a study of 76 countries, the University of Vienna's Dennis C. Mueller and George Mason University's Thomas Stratmann found a statistically significant negative correlation between government size and economic growth.14

Though a large portion of the literature finds no positive correlation between government spending and economic growth, some empirical studies have. For example, a 1993 paper by economists William Easterly and Sergio Rebelo looked at empirical data from approximately 100 countries from 1970-1988 and found a positive correlation between general government investment and GDP growth.15

This lack of consensus in the empirical findings indicates the inherent difficulties with measuring such correlations in a complex economy. However, despite the lack of empirical consensus, the theoretical literature indicates that government spending is unlikely to be as productive for economic growth as simply leaving the money in the private sector.

WHY DOES IT MATTER RIGHT NOW?

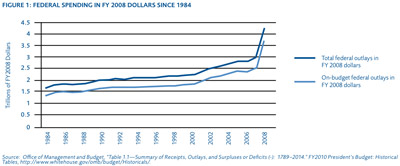

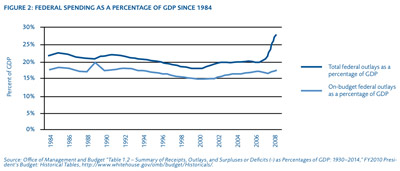

In 2009, Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which authorized $787 billion in spending to promote job growth and bolster economic activity.16 The budgetary consequences of this legislation and other government spending initiatives aimed at improving the economic outlook for the federal budget can readily be seen in recent federal outlays. As seen in figure 1, total federal outlays have risen steadily over time, and a sharp increase occurred after 2007. As seen in figure 2, total federal spending as a percentage of GDP has risen sharply in the last two years to nearly 30 percent. As explained above, this spending may have countervailing effects that could actually hamper economic growth by crowding out private investment.

CONCLUSION

Government spending, even in a time of crisis, is not an automatic boon for an economy's growth. A body of empirical evidence shows that, in practice, government outlays designed to stimulate the economy may fall short of that goal. Such findings have serious consequences as the United States embarks on a massive government spending initiative. Before it approves any additional spending to boost growth, the government should use the best peer-reviewed literature to estimate whether such spending is likely to stimulate growth and report how much uncertainty surrounds those estimates. These analyses should be made available to the public for comment prior to enacting this kind of legislation.

ENDNOTES

1. Richard E. Wagner, Fiscal Sociology and the Theory of Public Finance: An Explanatory Essay (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, Ltd., 2007), 28.

2. John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (Orlando, FL: First Harvest/Harcourt, Inc., 1953) 1964 ed.

3. Jane G. Gravelle, Thomas L. Hungerford, and Marc Labonte, Economic Stimulus: Issues and Policies, Congressional Research Service Report for Congress, December 9, 2009, http://assets.opencrs.com/rpts/R40104_20091209.pdf.

4. This is the concept of the "knowledge problem" elucidated by Friedrich A. Hayek, who explained that information necessary to foster efficiency in a market is dispersed among myriad participants and cannot be held by one central organization. For more information, see his essay, "The Use of Knowledge in Society," American Economic Review XXXV, no. 4 (1945): 519-30, http://www.econlib.org/library/Essays/hykKnw1.html.

5. Gordon Tullock, "Government Spending," The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, The Library of Economics and Liberty, http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc1/GovernmentSpending.html.

6. William F. Shughart, II, "Public Choice," The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, The Library of Economics and Liberty, http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/PublicChoice.html.

7. Gavin Wright, "The Political Economy of New Deal Spending: An Econometric Analysis," The Review of Economics and Statistics 56, no. 1 (February 1974): 30-38.

8. Christina Romer and Jared Bernstein, The Job Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Plan, January 9, 2009, http://otrans.3cdn.net/45593e8ecbd339d074_l3m6bt1te.pdf.

9. Robert J. Barro and Charles J. Redlick, "Macroeconomic Effects from Government Purchases and Taxes" (NBER Working Paper no. 15369, September 2009).

10. Valerie A. Ramey, "Identifying Government Spending Shocks: It's All in the Timing" (NBER working paper, October 2009), 32, http://econ.ucsd.edu/~vramey/research/IdentifyingGovt.pdf.

11. Benjamin M. Friedman, "Crowding Out or Crowding In? Economic Consequences of Financing Government Deficits," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1978, no. 3 (1978): 596-597.

12. Alberto Alesina, et al. "Fiscal Policy, Profits, and Investment" (NBER Working Paper no. 7207, July 1999).

13. Robert J. Barro, "Government Spending in a Simple Model of Endogenous Growth," The Journal of Political Economy 98, no. 5 (October 1990): S122-S124.

14. Dennis C. Mueller and Thomas Stratmann,"The Economic Effects of Democratic Participation" (CESifo Working Paper no. 656 (2), January 2002), http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=301260.

15. William Easterly and Sergio Rebelo, "Fiscal Policy and Economic Growth: An empirical investigation," Journal of Monetary Economics, 32 (1993): 432.

16. "The Act," Recovery.gov, http://www.recovery.gov/About/Pages/The_Act.aspx.