- | Regulation Regulation

- | Public Interest Comments Public Interest Comments

- |

Energy Conservation Standards for Standby Mode and Off Mode for Microwave Ovens; Petition for Reconsideration

The Regulatory Studies Program of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University is dedicated to advancing knowledge about the effects of regulation on society. As part of its mission, the program conducts careful and independent analyses that employ contemporary economic scholarship to assess rulemaking proposals and their effects on the economic opportunities and the social well-being available to all members of American society. This comment addresses the efficiency and efficacy of this proposed reconsideration from an economic point of view. Specifically, it examines how the relevant rule may be improved by more closely examining the societal goals the rule intends to achieve and whether this reconsideration will successfully achieve those goals. In many instances, regulations can be substantially improved by choosing more effective regulatory options or more carefully assessing the actual societal problem.

Introduction

The Regulatory Studies Program of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University is dedicated to advancing knowledge about the effects of regulation on society. As part of its mission, the program conducts careful and independent analyses that employ contemporary economic scholarship to assess rulemaking proposals and their effects on the economic opportunities and the social well-being available to all members of American society.

This comment addresses the efficiency and efficacy of this proposed reconsideration from an economic point of view. Specifically, it examines how the relevant rule may be improved by more closely examining the societal goals the rule intends to achieve and whether this reconsideration will successfully achieve those goals. In many instances, regulations can be substantially improved by choosing more effective regulatory options or more carefully assessing the actual societal problem.

Summary

On June 17 of this year, the Department of Energy (DOE) finalized a rule mandating new energy efficiency standards for standby and off modes for microwave ovens (hereafter, microwave rule).1 This regulation has proven to be controversial since the Department decided to use an estimate for the social cost of carbon (SCC) that was different from the one used at the time the regulation was proposed.2 The new SCC estimate was derived from an interagency report released between the time the microwave rule was proposed and when it was finalized.3

In response, the Landmark Legal Foundation has petitioned the Department to reconsider this regulation and reopen the final rule so that the public has the opportunity to comment on the new estimates of the social cost of carbon used in the rulemaking.4

The new SCC will impact not just this particular regulation, but numerous other DOE regulations as well. It is always a good idea to seek comment from the public when making important policy changes. In addition, given that the interagency group that arrived at the new estimate did not seek comment from the public on its methodology, DOE would be well advised to seek comment from the public here.

While I do not plan to comment here on the validity of the estimate of the social cost of carbon used in either the proposed version of the regulation or in the final regulation, I will argue that this opportunity should be seized to reconsider the regulation for other reasons.

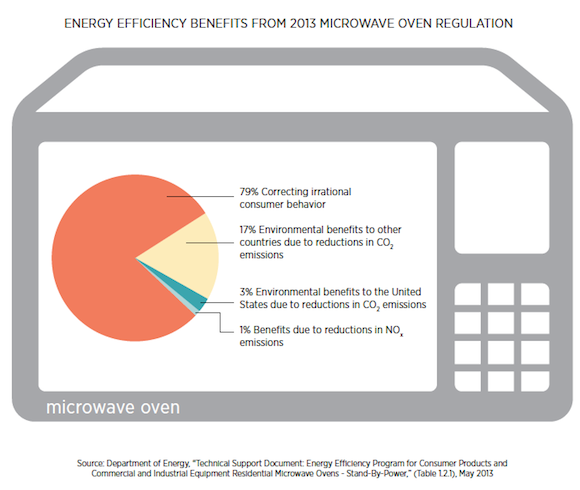

The estimates of benefits in the final Technical Support Document (TSD) for the microwave rule are highly questionable.5 This regulation fails to pass a benefit-cost test using the Department’s best estimates, even after including the additional benefits resulting from the higher estimate of the SCC. This is because the preponderance of the rule’s benefits, nearly 80 percent, are not related to reductions in carbon emissions, or even to any environmental effects at all. Instead, these benefits are based on the assumption that consumers behave in an irrational manner when purchasing microwave ovens and that the Department will be able to “fix” this behavior by issuing a regulation, thereby resulting in benefits to consumers. These “savings” should be excluded from the agency’s final analysis of benefits resulting from the regulation.

Irrational Consumer Behavior

Recent regulations emerging from the Department of Energy, the Department of Transportation, and the Environmental Protection Agency have been using alleged consumer irrationality as a justification for regulating.6 Consumers often choose to forgo savings in the form of lower energy or fuel bills in the future in order to pay a lower price for the product today. In the case of microwave ovens, the Department views this behavior as irrational and has chosen to ban the less energy efficient products from the market.7 Since consumers could choose the more energy efficient product without the regulation ever being implemented, these “operating cost savings” cannot be counted as a benefit of the regulation. Consumers can capture these savings on their own. Additionally, since consumers have fewer options available to them following implementation of the regulation and cannot capture the benefits of whatever attributes the less efficient products may have had that the more energy efficient products lack, this is clearly a cost and it is not accounted for in DOE’s cost estimates.

Estimates of Benefits

Using the Department’s primary estimate for the SCC, estimated benefits from reductions in CO2 emissions resulting from the microwave rule are $58.4 million per year (2011$). This number is dwarfed, however, by the supposed benefits resulting from correcting irrational consumer behavior, which are estimated at $234 million per year (2011$), implying that nearly 80 percent of the stated benefits from the regulation are due to correcting consumer irrationality. The chart below displays this information.8  Another troubling aspect of the regulation is that benefits from CO2 are combined to include both benefits to the United States as well as benefits to other countries, when Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidelines clearly advise otherwise. OMB recommends:

Another troubling aspect of the regulation is that benefits from CO2 are combined to include both benefits to the United States as well as benefits to other countries, when Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidelines clearly advise otherwise. OMB recommends:

Your analysis should focus on benefits and costs that accrue to citizens and residents of the United States. Where you choose to evaluate a regulation that is likely to have effects beyond the borders of the United States, these effects should be reported separately.9

While the recent TSD updating the social cost of carbon recommends that agencies include global benefits, in spite of the above OMB recommendations, the report did so without taking comment from the public.10 Additionally, this recommendation does not eliminate the need to be transparent, which means DOE should separate benefits to foreigners and benefits that will be captured by US citizens in its tables, which the Department currently does not do. This can easily be done, since the 2010 TSD estimating the SCC expected that benefits to US citizens will compose between 7 and 23 percent of total benefits.11 The chart above uses the midpoint of these values: 15 percent.

Given that the primary estimate of the total benefits resulting from this regulation is estimated at $294 million per year (2011$), and total costs are estimated at $66.4 million per year, subtracting the consumer “irrationality” benefits of $234 million produces net costs to society of $6.4 million per year (2011$).12 If DOE used a lower value of the SCC, like the estimate used in the proposed version of this regulation, that net cost figure would be even higher. The problem is further compounded if benefits to other countries are excluded from the estimates.

Discounting

It should be noted that I have chosen to value the costs and benefits here using a 3 percent discount rate because this is the only discount rate available for the SCC that is consistent with all the other costs and benefits estimated in the TSD. Given that OMB guidelines recommend using both a 3 percent and a 7 percent discount rate in regulatory impact analyses,13 it would be helpful if the SCC were also calculated at the 7 percent discount rate to provide an alternative measure of net benefits resulting from this regulation. This would also help address some of the uncertainty inherent in these types of estimates by providing a more consistent and defensible range of estimates of net benefits.

Conclusion

The Department of Energy would be wise to reopen the final microwave oven rule for comment. For the sake of transparency and accountability to the public, the Department should also take comments from the public on its new SCC estimate. And for the sake of good governance and efficient rulemaking, the Department should reconsider this regulation altogether since it likely fails a cost-benefit test, unless we make the unlikely assumption that regulators are able to guide citizens to more rational decisions and thereby provide benefits to consumers.