- | Medical Innovation Toolkit Medical Innovation Toolkit

- | Regulation Regulation

- | Data Visualizations Data Visualizations

- |

How Productive Is the FDA’s Human Drugs Program?

The Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Human Drugs Program provides assurance of the safety, effectiveness, and quality of pharmaceuticals. The work of the Human Drugs Program is carried out by the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), plus fieldwork done by FDA’s Office of Regulatory Affairs. In this short presentation we focus on one key measure of the Human Drugs Program’s productivity.

The Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Human Drugs Program provides assurance of the safety, effectiveness, and quality of pharmaceuticals. The work of the Human Drugs Program is carried out by the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), plus fieldwork done by FDA’s Office of Regulatory Affairs. In this short presentation we focus on one key measure of the Human Drugs Program’s productivity.

The FDA reports on its productivity in its annual report Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees. Each year’s Justification does not report much on years prior to the immediate past year. For example, the just-published 2017 report gives the Human Drugs Program’s productivity metrics for the 2015 fiscal year, but not for any years prior to 2015. Using past years’ Justification reports, here we compile key productivity metrics for the last decade.

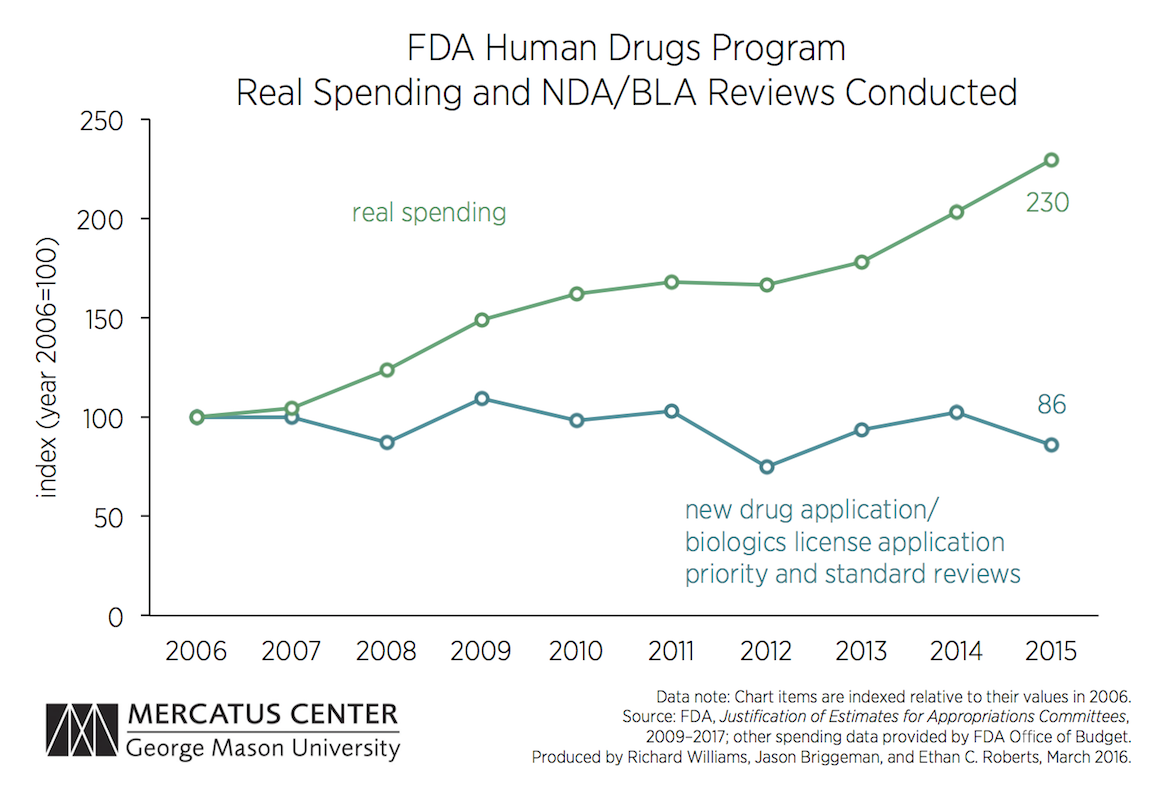

The table below reports on six productivity metrics, along with inflation-adjusted spending on the FDA’s Human Drugs Program. The chart, however, plots only the number of new drug application (NDA) and biologics license application (BLA) reviews conducted—the reviews that determine whether novel drugs (and biologics regulated by CDER) will be permitted. Obviously, not all of the drugs reviewed are allowed on the market.

The FDA Justification reports show that while annual real spending on the Human Drugs Program has more than doubled since 2006, the number of NDA and BLA reviews it conducts per year has not increased at all. But some outputs related to other Human Drugs Program responsibilities have increased sharply, particularly the number of post-market patient safety reviews and the number of examinations of imported goods.

The raw count of NDA reviews may not properly reflect the workload associated with such reviews. It may be that the FDA has increased the amount of information required for the typical NDA review and, in that case, the total amount of work done on such reviews would indeed have increased. But greater FDA capacity over the last decade has not yet led to an increase in the number of final new-drug reviews.

If one key goal is to increase the number of new drugs entering the system by increasing user fees, then there is a problem. Given that the FDA frequently notes that it has met its goals for the Prescription Drug User Fee Act, then the issue may be that there are disincentives to discover and submit new drug applications because of the increasing amount of information required. Independent of how else the FDA chooses to spend its growing resources, this should give pause to any request for further resources.