- | Technology and Innovation Technology and Innovation

- | Policy Briefs Policy Briefs

- |

“Information Sharing”: No Panacea for American Cybersecurity Challenges

After briefly outlining the current cybersecurity information sharing proposals, we will examine the performance of the many similar programs that the federal government has operated for years. The government’s inability to properly implement previous information sharing systems even internally, along with its ongoing failures to secure its own information systems, casts doubt on the viability of proposed government-led information sharing initiatives to improve the nation’s cybersecurity. We will then examine the flawed assumptions that underlie information sharing advocacy before exploring solutions that can comprehensively address the nation’s cybersecurity vulnerabilities.

As the number and cost of information security incident failures continue to rise, the federal government is considering legislative responses to address national cybersecurity vulnerabilities. Federal proposals from the executive and legislative branches emphasize increasing “information sharing” about cyberthreats among private and public entities to improve system preparedness. However, preexisting government, public-private, and private sector information sharing initiatives have not succeeded at preventing cyberattacks as proponents of these initiatives allege. Additionally, longstanding federal information security weaknesses render the federal government an especially poor candidate to manage large amounts of sensitive private data, as the recent massive information breach of the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) demonstrates.

After briefly outlining the current cybersecurity information sharing proposals, we will examine the performance of the many similar programs that the federal government has operated for years. The government’s inability to properly implement previous information sharing systems even internally, along with its ongoing failures to secure its own information systems, casts doubt on the viability of proposed government-led information sharing initiatives to improve the nation’s cybersecurity. We will then examine the flawed assumptions that underlie information sharing advocacy before exploring solutions that can comprehensively address the nation’s cybersecurity vulnerabilities.

What Do Information Sharing Initiatives Propose?

The premise behind cyberthreat information sharing initiatives is that network administrators who notice a new kind of attack or vulnerability can help others to defend against intrusion by quickly publicizing the discovery. In practice, however, private entities can be reluctant to share such threat information for several reasons, including their desires to protect customer privacy, trade secrets, or public reputation. Advocates argue that the federal government can increase information sharing among entities, and therefore improve cybersecurity, by extending legal immunity to private corporations that share private customer data with federal agencies in a compliant manner.

Several such proposals have been introduced this year. The House of Representatives passed the Protecting Cyber Networks Act in April of 2015, which would shield private entities that shared cyber threat indicators with federal agencies from legal action by aggrieved parties. The Senate’s version of an information sharing bill, the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act (CISA), proposes similar policies. On the executive level, president Obama proposed a plan to promote information sharing among private and public entities and created through executive order a new Cyber Threat Intelligence Integration Center (CTIIC) to coordinate information sharing under the Director of National Intelligence (DNI). The Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Department of Defense (DOD), Department of Justice (DOJ), and DNI would be empowered to receive, analyze, store, and disseminate sensitive threat data from private entities to varying degrees under each proposal. In contrast, members of the House who see protecting strong encryption as a solution to strengthen both privacy and security have passed an amendment to the Commerce, Justice, and Science appropriations bill to prevent the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) from weakening encryption standards. While information sharing proposals are currently intended to be voluntary, some have suggested that such initiatives will not work as intended unless made compulsory. On the other hand, sharing cyberthreat information with government agencies raises concerns from privacy and civil liberties groups, even when sharing is nonmandatory. Laws like CISA could open another channel for intelligence agencies to extract private data for criminal investigations completely unrelated to cybersecurity.

Existing Federal Sharing Programs Have Not Worked

Information sharing initiatives are not novel. A 1998 presidential order authorized the formation of public-private partnerships to share threat information within critical infrastructure industries. Dozens of such Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs) have coordinated cyberthreat information flows among public and private entities since that time. Additionally, at least 20 federal offices already carry out missions that prioritize information sharing and public-private cybersecurity coordination. The National Cybersecurity and Communications Center (NCCIC), a DHS cyberthreat coordination center, houses the US Computer Emergency Response Team (US-CERT), which has served as the primary cyberthreat collection, assistance, and notification center since it was founded in 2003. President Obama created the CTIIC in February 2015 to advance information sharing goals along with the NCCIC, the Federal Bureau of Intelligence’s National Cyber Investigative Task Force, DOD’s US Cyber Command, and “other relevant United States Government entities”—which could amount to several dozen offices. Such overlapping roles and unclear lines of communication results in waste, inefficiency, and poorer security outcomes.

Despite the ample resources devoted to this task, the federal government has struggled to effectively collect and share incident information internally and with the private sector. ISACs can cease to operate if members do not actually share valuable information. A DHS Inspector General Report finds that the NCCIC faces large challenges in effectively sharing information among the appropriate parties. As of October 2014, the NCCIC had not even developed a common incident management system to coordinate information sharing—five years after being formed to do so. US-CERT has yet to develop performance metrics to gauge and improve effectiveness, despite serving as the main federal cybersecurity consultant for over a decade. Additionally, private sector threat analysis efforts often outpace US-CERT in breach notification. Indeed, DHS has at times been unable to even adequately share threat information within its own offices. In March 2013, DHS’s own US-CERT issued a warning about Windows XP vulnerabilities to government and private sector partners. But by November of that year, DHS’ Inspector General reported that several DHS computers were still running a vulnerable version of Windows XP, even after other DHS representatives ensured they had stopped running that version.

The Congressional Research Service notes “greater information sharing may, in some instances, effectively weaken cybersecurity by creating an overwhelming amount of information, eliminating the capacity to pay attention to truly important alerts.” The federal government sought to overcome this challenge by developing technological tools to surveil network activity, called the “EINSTEIN” projects, yet these projects often run over cost and perform worse than anticipated. Indeed, the EINSTEIN projects failed to identify the recent OPM hack. However ambitious their design, these programs have so far proven too technologically crude to handle the complex central identification and communication efforts intended to protect federal systems. There may never be enough EINSTEINs in the world for DHS, DOD, and DOJ to adequately coordinate and respond to the massive amounts of private data that would be collected under CISA.

Systemic Security Weaknesses Plague Federal Systems

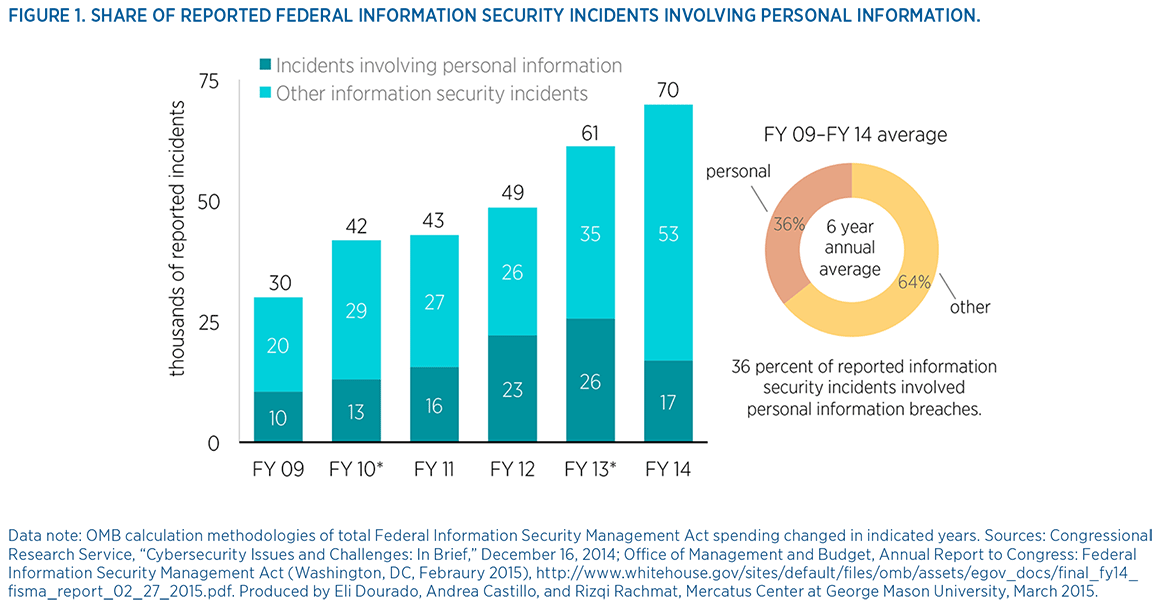

Federal information sharing initiatives have proven unsuccessful in stemming the number of reported agency information security failures. These longstanding cybersecurity weaknesses and failures render the federal government a poor candidate to manage more private data as has been proposed. The number of incidents reported to US-CERT increased by 1,169 percent since fiscal year (FY) 2006, reaching an all-time high of 69,851 last year. Additionally, federal agencies have in general struggled to secure personally identifiable information (PII) of personnel and civilians. Almost 40 percent of the roughly 300,000 reported federal information security incidents from FY 2009 to FY 2014 involved sensitive PII being potentially exposed to outside groups.

The recent OPM hack clearly highlights the dangers of entrusting massive amounts of private data to federal agency management. Recent reports reveal that, contrary to early official statements that hackers only gained a limited amount of information, the Social Security numbers and addresses of over 14 million current and former employees and contractors, including intelligence and military officials in the most need of data protection, were extracted by foreign hackers. In addition, hackers accessed reams of Standard Form 86 questionnaires used for conducting background checks, which contain sensitive data about applicants’ family, friends, and former coworkers. Despite serving as the central human resource department for the entire federal government, OPM did not employ any security staff until 2013. Much of the data was not even encrypted. Early reports that the federal government’s EINSTEIN threat detection system identified the breach were similarly incorrect; a product demonstration by an outside vendor reportedly first found the hack in April. Information sharing legislation could expand the circle of Americans harmed by such government breaches.

Importantly, the agencies that would be entrusted with significant new data extraction and management responsibilities under CISA reported alarming security breaches last year. DOJ employees downloaded malicious software onto agency computers 182 times in FY 2014 and reported a total of 3,604 incidents for the year. Of the 2,608 reported DHS failures, employees reported 1,816 pieces of computer equipment lost or stolen. DOD personnel downloaded malware onto network systems 370 times and reported roughly 2,500 employee policy violations in the past year alone, as well as 1,758 other incidents. Additionally, each agency has suffered major system infiltrations by malicious hackers in recent years—sometimes involving sensitive data extractions by hostile external groups. If these agencies’ already weak information management capacities are further strained, the rate of PII exposures could ultimately increase—and even have the unintended consequence of weakening cybersecurity and increasing attacks on federal systems. Malicious hackers would, after all, know that these ill-defended agencies would be managing massive amounts of potentially valuable data, thereby creating a tempting target for infiltration.

We Need Better Cybersecurity Solutions

The professional information security community is accordingly skeptical that such calls for top-down, government-driven information sharing of cyberthreats will actually diminish or prevent breaches. One poll of privacy and security experts from across the government, private sector, and academia finds that 87 percent do not believe that CISA-style information sharing initiatives will “significantly reduce security breaches.” Some respondents replied that while information sharing may be useful on the margins, placing it as the center of a top-down, government-driven panacea to protect national networks is inadequate and even counterproductive. Others in the security community are concerned that such initiatives merely use the guise of cybersecurity to push through measures secretly intended to increase surveillance of online activity.

Most agree that information sharing alone will not significantly improve cybersecurity preparedness. Industry studies find that external attacks only constitute 37 percent of reported root causes; system glitches and human error, respectively, make up 29 percent and 35 percent of the remainder. This Band-Aid solution does not address the core problems of poor security practices, inadequate user education and authentication requirements, and proper investment in defensive technology. In the worst-case scenario, high-profile information sharing measures like CISA will serve to ultimately weaken cybersecurity if they instill a false sense of security among government and private actors, leading them to neglect these other critical factors that are arguably more imperative for robust cybersecurity.

This is not to say that there is nothing to be done about cybersecurity. Instead of relying on a rigid top-down plan managed by poorly secured government agencies, public and private entities should work together using a “collaborative security” approach that fosters collective responsibility, evolutionary consensus, and nested decision making. Government officials should encourage, not weaken, good security practices like strong authentication and encryption. Legislation that protects and encourages the use of strong encryption will do far more to promote strong cybersecurity. Federal officials should stop contradicting each other on the need for strong encryption, and encourage efforts like CIO Tony Scott’s policy to require encrypted connection for all government websites. Likewise, government agencies should cease the practice of purchasing “zero-day exploits,” or publicly unknown security vulnerabilities, without notifying the relevant parties of discovered system weaknesses. Finally, government agencies can simultaneously improve their own system defenses and promote private sector security by purchasing cybersecurity insurance policies for their own networks and thereby stimulating this industry.