- | Government Spending Government Spending

- | Data Visualizations Data Visualizations

- |

Labor-Force Participation Rate Continues to Sink

The four and a half years since the Great Recession of 2008 could be called “the Dismal Recovery.” The most widely cited sign of progress toward a healthy economy has been the declining unemployment rate; however, the fall in the unemployment rate has largely been due to a shrinking labor-force participation rate rather than strong job growth. When you look at a broader range of labor market data, as in this week’s chart, the slow rate of progress toward recovery becomes apparent.

The four and a half years since the Great Recession of 2008 could be called “the Dismal Recovery.” The most widely cited sign of progress toward a healthy economy has been the declining unemployment rate; however, the fall in the unemployment rate has largely been due to a shrinking labor-force participation rate rather than strong job growth. When you look at a broader range of labor market data, as in this week’s chart, the slow rate of progress toward recovery becomes apparent.

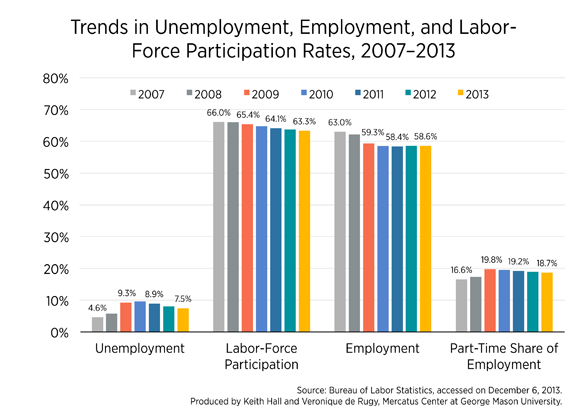

This week’s chart uses data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics to display annual unemployment rates, employment rates, labor-force participation rates, and part-time shares of employment from 2007 to 2013. The data suggest that the recent decline in unemployment is largely driven by discouraged workers dropping out of job searches.

The unemployment rate is calculated as the ratio of unemployed workers searching for a job to the total number of working-age people actively participating in the workforce or searching for work, known as the labor force. The employment rate is calculated as the ratio of employed workers to the total labor force. The labor-force participation rate is calculated as the ratio of the total labor force to the total working-age population. The participation rate reflects important trends like worker discouragement and labor-market exit.

The labor-force participation rate has been steadily dropping for the past seven years. In 2007, the rate was 66 percent; in November, that rate dropped to 63.3 percent. In the two most recent jobs reports, the labor-force participation rate has been at its lowest levels in nearly 35 years. Further, the entire drop in the unemployment rate in 2013 so far—from 7.8 percent in December 2012 to 7.0 percent last month—has been from the decline in the labor force rather than from job growth. The employment rate, likewise, has consistently declined, with only 58.6 percent of the population employed—lower than at the end of the recession in mid-2009.

These two trends help explain why the unemployment rate has been declining. While some workers have thankfully found gainful employment in recent years, many others have grown so frustrated by poor economic conditions that they have simply stopped looking for work. Since the unemployment rate only measures Americans who are actively searching for work, these discouraged workers are not counted. What’s more, the many high-skilled Americans who temporarily accept part-time or lower-paying jobs to scrape by in hard economic times are counted as “fully employed” workers by official unemployment statistics.

This episode serves as another reminder of the challenges of fairly interpreting government statistics on the labor market. The unemployment rate simply does not capture the tough realities that discouraged and underemployed American workers face daily. Only when a decrease in the unemployment rate is accompanied by increased labor-force participation and decreased underemployment will there be cause for celebration.