- | Academic & Student Programs Academic & Student Programs

- | Government Spending Government Spending

- | Policy Briefs Policy Briefs

- |

Locking Out Prosperity: The Treasury Department’s Misguided Regulation to Address the Symptoms of Corporate Inversions While Ignoring the Cause

Over $2 trillion of US corporate profits have been systematically locked out of the US economy by an outdated tax system. One major symptom of the poorly designed worldwide corporate tax rules in the US is the rise of corporate inversions, where a domestic firm merges with a foreign firm and moves the new corporation’s headquarters abroad.

Key Findings

- The United States has the highest corporate tax rate in the developed world and is one of just a few countries that taxes the worldwide income of domestic businesses.

- High numbers of inversions from 2012 through 2015 show that the tax savings that come from moving corporate headquarters abroad are financially worthwhile for specially situated firms meeting the Treasury’s ownership requirements.

- The Treasury Department has responded to corporate inversions by issuing regulations that raise the cost of inversion by increasing the complexity of international corporate merger rules.

- Instead of trying to reduce the number of corporate inversions by issuing more complex regulations, the United States should eliminate a major cause of inversions by moving toward a territorial tax system and a significantly lower corporate tax rate.

- If the United States had a lower corporate tax rate than other countries, the distinction between a worldwide or territorial tax system would make very little difference.

Over $2 trillion of US corporate profits have been systematically locked out of the US economy by an outdated tax system. One major symptom of the poorly designed worldwide corporate tax rules in the US is the rise of corporate inversions, where a domestic firm merges with a foreign firm and moves the new corporation’s headquarters abroad.

In response to some highly publicized corporate inversions, the Treasury Department has issued regulations that raise the cost of inverting by increasing the complexity of international corporate merger rules. Treasury’s regulatory response addresses the symptoms, but it fails to address the cause of corporate inversions. Instead of trying to address the symptoms of corporate inversions by issuing more complex regulations, the US should address the cause of inversions by moving toward a territorial tax system and a significantly lower corporate tax rate.

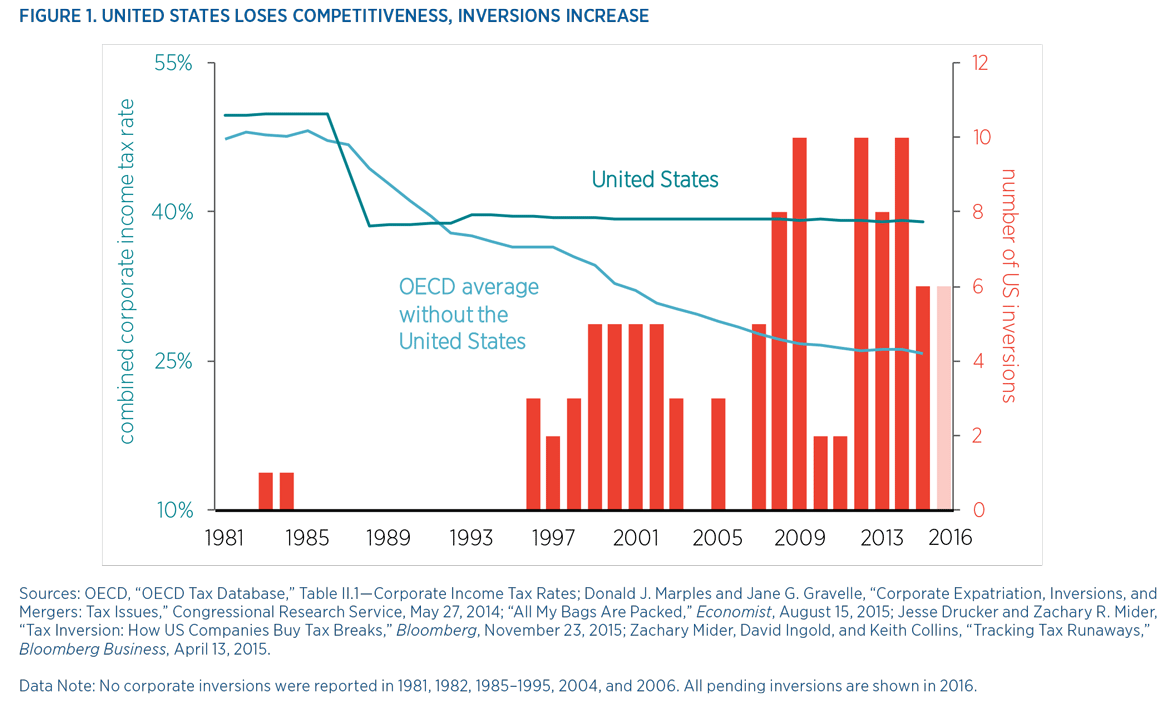

The US International Tax System

Corporate taxation in the US has two distinct characteristics: tax rates are high, and they are imposed on worldwide income. The US has the single highest combined corporate tax rate in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the third-highest rate in the world behind the United Arab Emirates and Chad. The average top combined US corporate tax rate is 39.1 percent, and the US is one of just three OECD countries not to lower corporate tax rates in the last 15 years. US businesses face some of the strongest incentives to move corporate business activity abroad to both lower taxes and meet emerging demand in foreign markets. The result is depressed investment in the US, which impedes both job creation and wage growth.

The corporate income tax is inefficient and widely recognized as needing fundamental reform. The burden of corporate taxes falls on people—generally on shareholders through lower returns and on workers through lower wages, although the size of the burden on each is debated. The corporate tax penalizes business activity by taxing corporate income twice and requires a bevy of accountants and lawyers for compliance. Lowering or eliminating the corporate income tax is the only way to decrease the underlying incentive for businesses to relocate to low-tax countries.

Compounding high tax rates, the United States is one of just six OECD countries that attempts to tax the worldwide income of its domestic corporations. Worldwide tax systems, like that of the United States, tax all income of domestically headquartered businesses, including income earned by subsidiaries operating abroad. Firms are allowed to defer paying taxes on “active” foreign income that has not yet been repatriated. Often referred to as a tax “loophole,” deferral of income from controlled foreign corporations is the largest corporate tax expenditure. Deferring taxes on foreign income allows US firms to compete abroad without the additional burden of US taxes.

Under the worldwide system, a Nevada-based US corporation that earns $100 of profit in Canada is at a fundamental disadvantage compared to an identical corporation headquartered in Canada. After getting taxed at Canada’s top marginal rate of 26.3 percent, the US corporation can then “repatriate” the remaining $73.70 to the US. However, the full $100 of profit is again taxed by the US, resulting in a $35 tax liability. The US firm gets a foreign tax credit for the $26.3 paid to Canada and has to remit an additional $8.70 to the IRS. The IRS collects $8.70, leaving the US-based firm $65 in after-tax profit. However, the identical Canadian competitor retains a higher after-tax profit of $73.70. Canada does not tax its firms’ foreign profits. While the US worldwide system does not distort domestic competition (all firms, foreign and domestic, are taxed equally), it does place US firms at a tax disadvantage when doing business in Canada and around the world.

History of Inversions and Instructive Legislative Reforms

Beginning in the 1990s, the Treasury has repeatedly attempted to curtail inversions. Several notable corporate inversions—and the resulting legislation to prevent other companies from doing the same—illustrate the ineffectiveness of policy reforms to date.

1996: Helen of Troy Inverts, Treasury Responds

Helen of Troy Limited, a publicly traded manufacturing firm, carried out one of the first notable public corporate inversions in 1996. The Texas firm formed a subsidiary company in Bermuda in 1993 called New Helen of Troy. This subsidiary company allowed Helen of Troy to reorganize into a Bermuda-based company. The transfer of shares from the domestic Helen of Troy to New Helen of Troy in Bermuda was not recognized as a taxable transaction at the time. Exceptions for the transfer of certain types of stocks or security exchanges in the tax code allowed Helen of Troy to circumvent rules that were explicitly designed to prevent tax avoidance. The Treasury subsequently updated a regulation to prohibit inversions of a similar design.

Inversion Frenzy and Section 7874

Despite the new rules after Helen of Troy, the late 1990s and early years after 2000 brought an increase in corporate inversions. Tyco International, Fruit of the Loom, and Chrysler all inverted in the late 1990s. In a 1999 testimony before the House Committee on Ways and Means, John Loffredo, vice president of the newly merged DaimlerChrysler, cited tax disadvantages in the United States as a primary reason to move abroad: “There are many US companies which have foreign operations and they are put at a competitive disadvantage in the global economy, just because they are competing against companies who do not have to follow the way the US tax system taxes foreign operations.”

Rather than responding by reforming the worldwide tax system and lowering the corporate tax rate, Congress added section 7874 to the Internal Revenue Code in 2004. Section 7874 attempted to identify tax-driven inversions by arbitrary criteria, stating that if 60 percent or more of the foreign corporate ownership stays the same after an acquisition, and the former owners of the domestic corporation and the foreign corporation do not have substantial business activity in the new location, it will be treated as a “surrogate foreign corporation.” A tax is then levied on the gains from transferring assets of any type out of the United States for 10 years from the date of inversion. Section 7874 increased the cost of inversion, but it did not eliminate all tax benefits to US firms from such transactions.

Following the addition of section 7874, five firms reincorporated abroad in 2007, followed by eight firms in 2008. The corporate inversion rate reached its pre–section 7874 level by 2008, and as a result, Congress strengthened the ownership test in 2009 by clarifying the statutory language in Notice 2009-78.

Where There’s a Will to Invert, There’s a Way

Instead of reincorporating in locations like Bermuda that had zero corporate income tax, corporations began to focus on reincorporating in countries in which they already had significant operations, but still had lower tax rates relative to the United States. This was a way to avoid the substantial business condition in section 7874 while still lowering the corporation’s tax burden.

In 2012, and again in September 2014, the Treasury worked to close the so-called loopholes used by corporations in several inversions. The Treasury has successfully increased the cost on corporations seeking to leave the United States. However, sustained high numbers of inversions from 2012 through 2015 show that the tax savings are still financially worthwhile for specially situated firms meeting the Treasury’s ownership requirements, as shown in figure 1. Since the strengthening of rules in September 2014, more than 12 US-based firms have announced tax-motivated inversion plans.

On November 19, 2015, the Treasury announced new guidance to narrow the pool of potential foreign inversion partners and make it harder to meet initial ownership requirements. The new rules are the Treasury’s second attempt in 14 months to curtail corporate inversions, and Treasury Secretary Jack Lew said they would issue additional rules in the coming months. The United States should work to create a favorable tax climate that attracts and retains US corporations instead of attempting to increase the costs of tax-motivated business migration through increased regulation and tax complexity.

The Treasury’s regulations have also stopped economically motivated mergers. Firms may merge for any number of reasons, and prohibiting firms from organizing in the most efficient way is harmful to the whole economy. Even if the merger is not tax-motivated, taxes generally still play a role. For example, a newly merged United States and foreign firm would very likely not locate its new headquarters in the US because of the high tax rates and the worldwide tax system.

Territorial Taxation: An Alternative to the Worldwide System

A system of territorial taxation only taxes income earned within the country’s borders. Taxing income where it is earned levels the playing field, so that operations in one jurisdiction are taxed at the same rate, regardless of parent ownership. In contrast, the US worldwide system was designed in the 1960s to create equity among domestic taxpayers regardless of where they did business. At the time of design, there were fewer multinational businesses; thus a smaller number of firms were affected by international tax rules. Today, almost every medium-sized and large company has an international presence, placing unnecessary pressures on the rules of an outdated international tax system.

Critics of territorial taxation often claim the system will reduce domestic investment, export domestic jobs, and decrease federal revenue. Counter to these fears, the academic literature shows that foreign investment is actually a complement to domestic investment. Under territorial taxation, firms should be expected to expand investments both in the United States and abroad—benefiting all parties involved. For example, reducing a barrier for US business to invest in foreign emerging markets will allow the US economy to benefit from growth abroad. Given the correct policy environment, global investments can be researched, developed, and managed from the United States. Three recent transitions to territorial taxation in the United Kingdom, Japan, and New Zealand show that territorial systems outperform worldwide tax regimes in creating jobs and increasing corporate tax revenue.

Under a territorial system, corporate profits can flow to their highest-value use, helping expand the economy. The US system of worldwide taxation locks corporate profits out of the US economy, forcing corporations to either reinvest or park the profits abroad while they wait for a lower US corporate tax rate. The tax penalty paid on repatriated earnings keeps an estimated $2 trillion of US corporate profits permanently reinvested overseas. US tax policy keeps much of these earnings from being invested in American infrastructure, factories, and research and development; it also prevents them from being paid out to American investors and retirees as dividends.

Policy Recommendations

If the United States wishes to restore its international competitiveness, it must reduce corporate tax rates and move to a territorial system of taxation. This is not a risky move; OECD countries around the world have already heeded the warning signs and implemented reforms. If the United States wishes to continue to foster innovation and enterprise, it will follow its OECD counterparts and open its doors to corporate business once again.

Specifically, US policymakers should lower the top marginal federal corporate income tax rate to be no higher than the OECD average of 25 percent. Truly competitive reform would ideally eliminate the corporate income tax altogether. Other approaches would be to lower the top marginal federal rate to 20 percent so that the combined federal and state corporate tax rates are no higher than the OECD average; or the United States could reduce the top rate to around 12 percent to match that of Ireland, which has the lowest OECD corporate tax rate at 12.5 percent. This would give the United States the lowest rate among competing countries. It should also be noted that if the United States had a lower corporate tax rate than other countries, the distinction between a worldwide or territorial tax system would make very little difference.

Recent proposals for temporary repatriation at lower tax rates—a “repatriation holiday”—should be resisted. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates such proposals may raise revenue in the first two years, but will lose significantly more in subsequent years, as evidenced by a similar holiday in the 2004–2006 period. The Joint Committee on Taxation further warns that another repatriation holiday may “signal that such holidays will become a regular part of the tax system, thereby increasing the incentives to retain earnings overseas,” further locking US profits out of the country.

The United States has long been an international symbol of support for private enterprise. However, corporate revenue is moving abroad to escape the burdensome corporate tax code and increasingly stifling regulations on corporate inversions. Stamping out corporate inversions by reducing American companies’ ability to move their headquarters elsewhere applies a Band-Aid to a much larger issue, and it is a Band-Aid that will only result in continued migration of US corporate businesses overseas. The proper policy to retain and attract business investment in the United States is to lower the corporate tax rate and move toward a territorial tax system.

To speak with a scholar or learn more on this topic, visit our contact page.