- | Regulation Regulation

- | Federal Testimonies Federal Testimonies

- |

OIRA Alone Could Not Achieve President Carter's Goals

Testimony before the House Committee on the Judiciary

Thirty-five years ago, President Jimmy Carter began an experiment to, in his words, “regulate the regulators” to “eliminate unnecessary federal regulations.” His experiment was to form, through the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1980, the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs within OMB to allow the president to gain control over the regulatory agencies. We have now had 35 years of experience to see if President Carter’s goals have been achieved. They have not.

Thank you Chairman Marino, Ranking Member Johnson, and members of the Committee for the opportunity to testify today. I am vice president for policy research at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. My three-and-a-half decades of experience with rulemaking and regulatory analysis includes work at the Food and Drug Administration and a stint at the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) in the Office of Budget and Management (OMB) reviewing rules from other agencies.

Thirty-five years ago, President Jimmy Carter began an experiment to, in his words, “regulate the regulators” to “eliminate unnecessary federal regulations.” His experiment was to form, through the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1980, the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs within OMB to allow the president to gain control over the regulatory agencies. We have now had 35 years of experience to see if President Carter’s goals have been achieved. They have not. To be clear, OIRA does excellent work. But even if the office (1) had more than 45 people to control hundreds of thousands of regulators; (2) wasn’t constrained to stay away from agencies that are political favorites; and (3) covered independent agencies, it would still be, as some have described it, “a speed bump.”

OIRA will always serve as only a minor check on the quality of regulations implemented because it is in the same branch of government as the regulatory agencies, and it often carries less political clout than the agencies whose work it reviews. A credible effort by any OIRA administrator to push back on a regulation, therefore, depends on whether the administrator knows if OIRA can win the political argument that will follow. Having to win a political battle to ensure that analysis is done well and is considered in rulemaking is never going to provide the kind of quality check that the last six presidents have called for. The issues for OIRA include:

- There is substantial evidence that President Carter’s experiment has failed. The quality of economic analysis in rulemaking is poor, which leads to poor regulations. More troubling, agencies are seeking to evade the safeguards of the Administrative Procedure Act through a variety of “stealth” regulations.

- The consequent regulatory accumulation imposes a considerable burden on American households and a drag on the economy.

- Addressing regulatory accumulation requires comprehensive reform, and staffing up OIRA would only be a small element of that reform.

The Failure of OIRA as Federal Watchdog

What is the evidence that this experiment has failed? President Carter wanted to eliminate unnecessary federal regulations. Today, far too many regulations fail to address a problem, do not solve any problem, or have unintended consequences. President Carter also instituted the first major requirement for economic analysis (Executive Order 12844) that OIRA is expected to oversee.

Poor economic analysis: We have observed through years of scholarly research that only a small fraction of rules have an analysis, the analysis is often poorly done, agencies rarely use the analysis as part of their decision-making, or analysis is done after decision-making to justify the agency’s position.

Among other research, the Mercatus Center’s Regulatory Report Card confirms these findings. For the period from 2008 through 2012, the Regulatory Report Card found an average score of 52 percent, or a grade of F for many schools, for 108 economically significant regulations, using 12 criteria based on Executive Order 12866.

OIRA is simply too small: How could OIRA possibly address these problems? With a current staff of 45 in fiscal year 2014, OIRA is simply too small to provide effective oversight to the hundreds of thousands of employees at federal agencies producing regulations—with more than 200,000 employed in rule-writing agencies alone. In 1981, OIRA had a staff of 77, and federal agencies had total staffing of 115,047. Over the years, OIRA’s mission has been cut back from reviewing all regulations to only reviewing economically significant ones. But even that remains a daunting task when the budget devoted to rulemaking by regulatory agencies outspends the OIRA’s budget for reviewing regulations by a factor of 7,000 to 1.

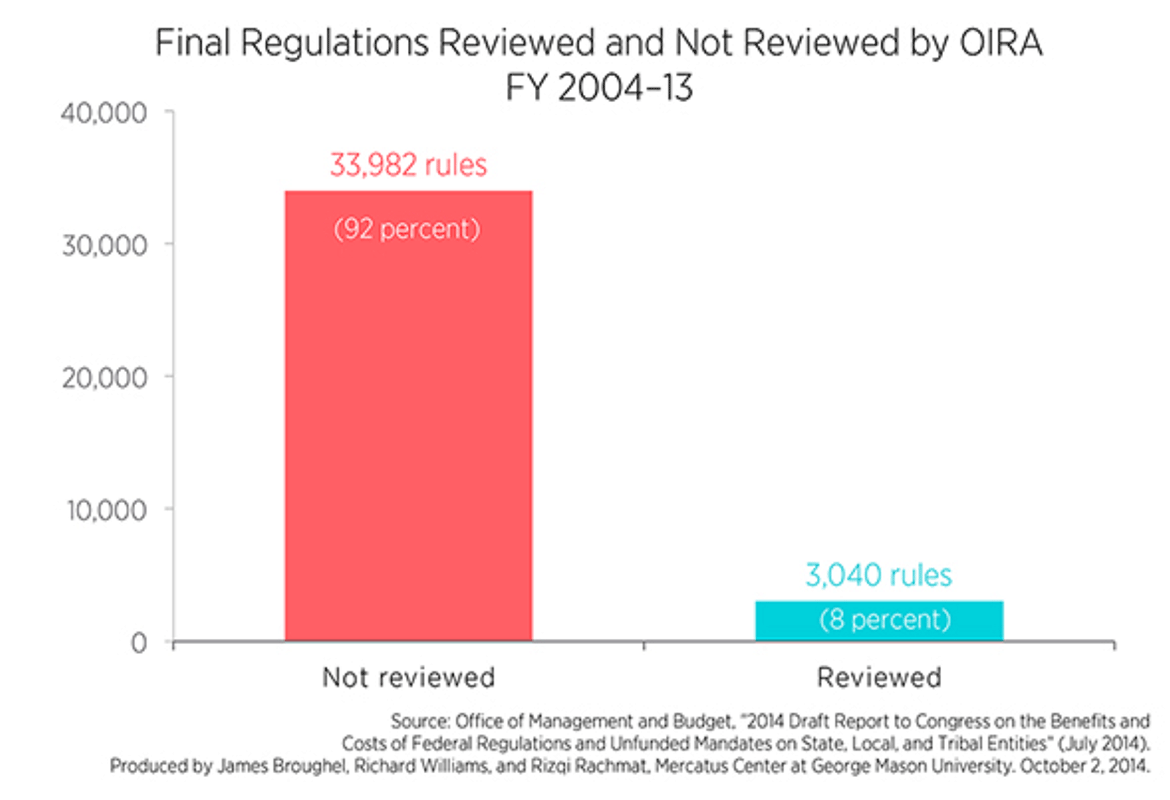

Over the last decade, rulemaking agencies finalized 37,000 regulations, but OIRA reviewed only 3,000. Of these, only 116 had both benefits and costs appearing in OIRA’s annual report. (See attachment 1.) What’s more, OIRA has evolved from “being a watchdog whose job was to ensure that agencies used economic logic and quality benefit-cost analysis when regulating to being a ‘conveyor and convener’ and ‘information aggregator’ for the agencies.”

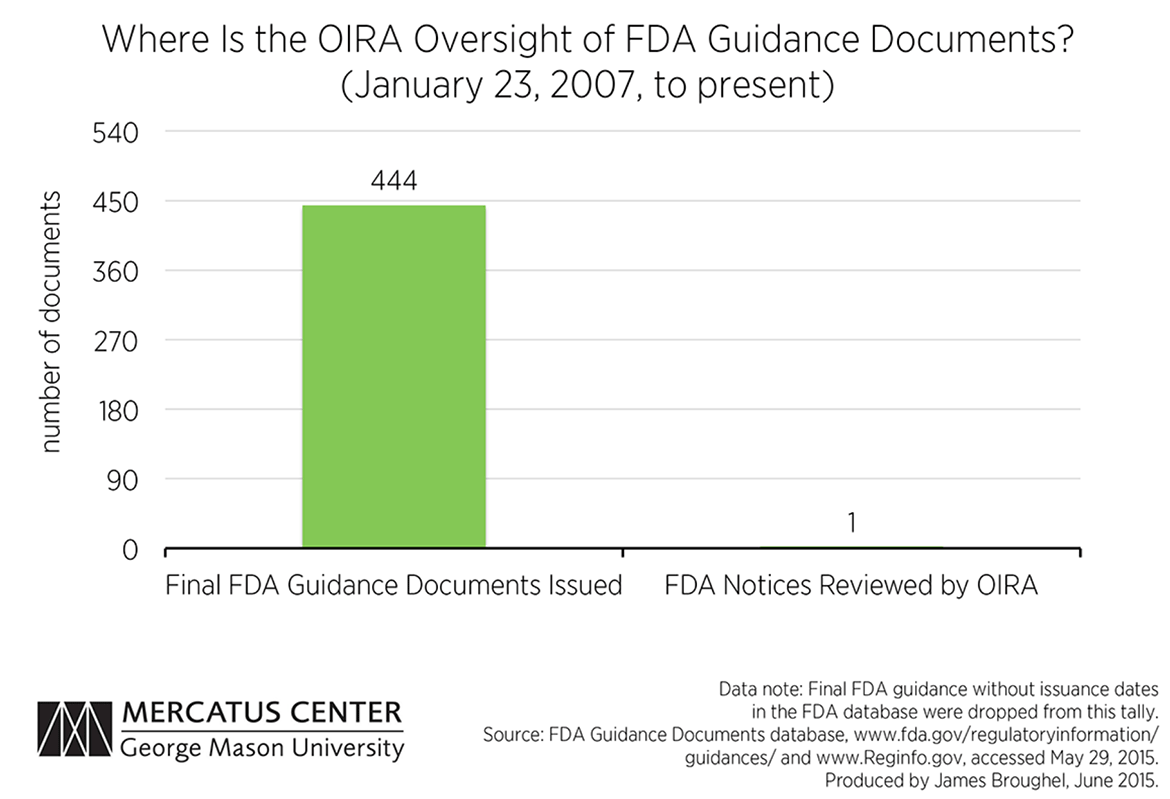

“Stealth” regulations: OIRA cannot regulate the regulators effectively because the regulators have numerous ways of creating “stealth” regulations to avoid OIRA review. Examples include “sue and settle” lawsuits, guidance documents, and other nonregulatory means of compliance. Guidance documents have the same effect, in practice, as regulations—but without notice and comment safeguards. Rule interpretations work in a similar fashion. For example, between January 2007 and now, there has been exactly one FDA notice reviewed by OIRA. (See attachment 2.) A recent GAO report suggests that the FDA is not an outlier; procedures and oversight for guidance documents are severely lacking. Alternatively, to get around OIRA, agencies can collaborate with interest groups through “sue and settle” lawsuits to get a consent decree, or work with state regulators to establish what become de facto national standards.

The Cost of Regulatory Accumulation

When President Carter took office in 1977, there were 84,729 pages in the Code of Federal Regulations. By 2014, there were 175,268 pages, an increase of 107 percent. These pages contain over 1 million requirements that would take an average person three years to read, although many more to comprehend. While the number and scope of regulations has continued to grow, agencies have largely failed to follow the rulemaking standards laid out in the executive orders. This growth has not been costless; one estimate shows that without those additional regulations, American families would be richer by an average of $277,100 per household.

The Need for a Comprehensive Solution

With the massive growth in federal regulations during the last 35 years, every American president since President Carter has embraced the idea of economic analysis to try to ensure that only necessary regulations are passed. For nearly 70 years, presidents have complained about their inability to manage the regulatory agencies. Jimmy Carter said that although he knew that “dealing with the federal bureaucracy would be one of the worst problems [he] would have to face,” the reality had been even “worse than [he] had anticipated.” Even President Obama noted in 2011 that sometimes the rules get out of balance, “placing unreasonable burdens on business—burdens that have stifled innovation and have had a chilling effect on growth and jobs.”

Evidence of each president’s failure to control the regulatory agencies is surely illustrated by “midnight rules.” In general, these rules are rushed and contain worse analysis than rules usually do. They are enacted after a new president is elected and before the new president is inaugurated. Given the surge that we are observing in rules lately, there may be a new category of midnight rules. The Congressional Review Act allows Congress to overturn rules (with presidential signature) within 60 days of passage. It appears to be the case that agencies are trying to finalize big rules prior to two months before inauguration to ensure that a new administration cannot overturn them.

After 35 years of research showing—along with presidential statements conceding—that the system is not working, it is time to admit that Congress must address these problems. While staffing up OIRA will be helpful, it will not solve the problems that President Carter and every president since has identified. Just as the problem is systemic and nonpartisan, so must the solution be.

Comprehensive reform is required to ensure that Congress has the necessary economic (and risk) information to effectively exercise oversight over regulations prior to their being issued. This information must also inform Congress as to when regulations or regulatory programs need to be enhanced, modified, or eliminated. Congress cannot do this alone—rather, stakeholders must be allowed access to judicial remedy when agencies fail to do the required analysis or do so badly. Without these kinds of remedies, we will continue to experience the same failures as we have observed over the last 35 years.

Attachment 1. OIRA Quality Control Is Missing for Most Regulations

Richard Williams, James Broughel | Oct 01, 2014

Over the last decade, federal regulatory agencies finalized more than 37,000 regulations, yet 92 percent of rules escaped review by the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), a small office tasked with reviewing significant regulatory actions promulgated by such agencies. Of the roughly 3,000 rules OIRA did review, only 116 have estimates of both benefits and costs appearing in OIRA’s annual report. Relative to the cost of many of these regulations, expecting agencies to analyze benefits and costs before issuing a rule is a fairly low bar to set.

The numbers suggest that the analysis of rules reviewed by OIRA is severely lacking in most cases. Of roughly 3,600 rules finalized last fiscal year, only seven had estimates of both benefits and costs appearing in OIRA’s report.

By confirming that agency actions are consistent with executive orders that set standards for regulatory analysis, OIRA is charged with ensuring that analysis meets minimal levels of quality and that agency rules are informed by those analyses. Each year OIRA puts out a report with details on the costs and benefits of the US regulatory system, but the report provides little insight because so many regulations escape review by OIRA. These missing rules also lack OIRA’s critical quality control check.

Most rules that avoid OIRA review are not deemed “significant,” meaning they aren’t expected to have large economic impacts, raise novel legal issues, or meet certain other criteria signifying the importance of a regulation. Yet, even if any of these rules by themselves might be small, cumulatively their effects can be large. Even worse, the rules that have estimates of both benefits and costs in OIRA’s report are not necessarily the ones that are most important to the American public. Of fiscal year 2013 rules, OIRA reports benefits and costs for a rule that defined “gluten-free” for the purposes of labeling foods that are gluten-free, but four major regulations emanating from the Affordable Care Act do not have any benefit or cost information, and none of the regulations implementing the Dodd-Frank Act have estimates of both benefits and costs. This last point is not surprising, as independent agencies (including most financial regulators) do not have to comply with executive orders setting regulatory analysis standards. Still, these examples suggest the true costs to the public are simply not captured in OIRA’s report.

OIRA performs an important role, but its staff is too small (45 in fiscal year 2014) relative to the hundreds of thousands of employees working in regulatory agencies to provide effective oversight. This means that there is no effective check on the vast majority of regulations, where there is often a total absence of analysis, analysis is ignored in the decision-making, or analysis is made to conform with a predetermined decision.

Attachment 2: Where Is the OIRA Oversight of FDA Guidance Documents?

Richard Williams, James Broughel | Jun 09, 2015

Federal agencies issue guidance documents that typically consist of sets of instructions or announcements written to inform regulated parties how to stay in compliance with the law. Owing to a confusing set of events, it is unclear whether these documents are receiving executive branch oversight from the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA). In the case of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), hundreds of guidance documents appear on its website, yet there is almost no evidence of oversight from OIRA.

On January 23, 2007, then-President George W. Bush issued Executive Order 13422, requiring executive branch regulatory agencies to submit their significant guidance documents for review by OIRA. OIRA, an office located within the Office of Management and Budget, was already tasked with reviewing other significant regulatory actions to ensure that such actions are supported by strong technical evidence. As such, it was natural for the same office to review guidance documents likely to have significant impacts. Upon entering office, President Obama repealed President Bush’s executive order.

The Office of Management and Budget, however, still maintains the right to review significant guidance, as it did even before the Bush executive order. The question that remains is the extent to which OIRA is reviewing these documents. One source that allows analysis of this activity is the FDA’s new guidance document database. According to this database, the FDA has issued 444 final guidance documents since President Bush issued his executive order in 2007. The pace of guidance issuance has remained steady over time, with the FDA finalizing on average four documents a month under both the Bush and Obama administrations. This figure is likely an underestimate since many documents in the FDA database are not even dated or are not labeled as draft or final. These documents were excluded from our analysis.

Meanwhile, the OIRA website lists only one FDA “notice” as having been reviewed during this period. The OIRA website is vague as to what documents are included in its “notice” category, saying only that these are documents that announce new programs or agency policies, which presumably includes guidance documents. Alternatively, it is also possible that informal review of FDA guidance is taking place that is not tracked on the OIRA website. If this is the case, this suggests a serious transparency problem exists. Regardless, the statistics available to the public suggest that there is little OIRA oversight of FDA activities when it comes to guidance.

The FDA is just one of dozens of executive branch and independent agencies that have the ability to issue guidance. If the FDA experience is representative of oversight at these other federal agencies, this is reason for concern since the effects of agency guidance often mirror those of regulations. In fact, a recent report by the Government Accountability Office chastised several agencies for a lack of compliance with agency good guidance practices. This suggests that both procedures and oversight are lacking with respect to guidance and need improvement.