- | Healthcare Healthcare

- | Policy Briefs Policy Briefs

- |

The Political Economy of Medicaid Reform: Evidence from Five Reforming States

Fiscal policy at both the federal and state levels is on an unsustainable path. Entitlement reform in America—particularly Medicaid reform—is shifting from a question of whether cuts should be made, to how much must be cut? To better understand best practices in Medicaid reform, we explore five recent state-level Medicaid reforms and their ability to simultaneously reduce costs, maintain or increase access, and survive the politics of reform.

Fiscal policy at both the federal and state levels is on an unsustainable path. Entitlement reform in America—particularly Medicaid reform—is shifting from a question of whether cuts should be made, to how much must be cut? To better understand best practices in Medicaid reform, we explore five recent state-level Medicaid reforms and their ability to simultaneously reduce costs, maintain or increase access, and survive the politics of reform.

MEDICAID'S RISING BURDEN

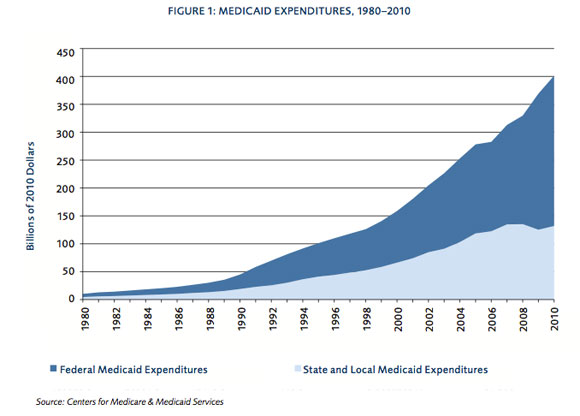

Medicaid is the United States’ major health care financing system for the poor, some elderly, and the disabled. In 2010, the most recent available data, annual Medicaid spending totaled around $400 billion and accounted for more than 15 percent of U.S. health expenditures[1]. While final data for 2011 is not yet available, average monthly enrollment is estimated to exceed $55 million, with over 70 million Americans covered for one or more months[2].

Although every state has ostensibly implemented Medicaid reforms over the last 10 years, combined federal and state expenditures grew from 2.0 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2000 to 2.7 percent in 2007. Some cost-saving reforms are politically dead ideas, while other—more popular—reforms only drive up costs. Successful reforms that provide a combination of cost reduction and maintained or increased access are hard to find. Thus, the easier path has been to increase expenditures.

THE DYNAMICS OF REFORM

Florida Medicaid reform of 2005

The main feature of Florida’s 2005 pilot program was the shifting of enrollees in Broward and Duval counties to managed care networks—three other counties were later added. In theory, these networks would control costs by matching enrollees with service providers. They would act as a buffer against inappropriate use (e.g., emergency care for basic treatments). The 2005 reforms also introduced benefit flexibility, incentives for healthy decisions, and premium assistance.

The results of Florida’s five-county pilot project were described as “a decided success.”[3] But a highly publicized Georgetown University study from April 2011 claimed the program did not produce significant results, limited access to prenatal care, and saved costs through low provider reimbursement rates.[4]

Florida is currently awaiting federal approval for expansions to the program. Many parties, such as researchers at Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute,[5] are opposed to the expansion, but the case has weak evidence of cost and coverage reductions, and significant—though not insurmountable—political barriers to reform.

Idaho Medicaid reform of 2006

Idaho’s Medicaid reform aimed to tailor coverage to enrollee needs. The greater flexibility promised to reduce costs and provide care more consistent with needs. The reforms also called for healthy choice initiatives, premium sharing, consolidated purchasing of prescription drugs and medical supplies at lower prices, and other cost reductions.[6]

Idaho’s spending increased following the 2006 Idaho Medicaid Simplification Act due to its segmented approach, which reduced the risk pool causing significant adverse effects. By segmenting people into separate risk categories, the high-risk pool became underfunded, and an excessive number of risky enrollees were wrongly placed in safer pools.

The reforms were popular at the time, and then-Governor Dirk Kempthorne encountered minimal opposition.[7] This was partly because of his willingness to hold town hall meetings and public forums to discuss the reform proposal. Kempthorne combined the topics of cost savings and state control versus federal control: Idaho’s reforms promised to not leave anyone without coverage, to reduce costs, and to return more power and control to the state.

Rhode Island Global Consumer Choice Compact of 2008

Rhode Island’s Consumer Choice Compact of 2008 set spending for five years and gave state leaders flexibility to introduce market principles to the Medicaid program. The plan encouraged cost control through an incentive system: When the state spent less than the capped amount, it could keep a fraction of the federal money. In its first two years, the program cut Medicaid spending by $1.1 billion. The global waiver alone saved more than $100 million in its first year.[8]

Then-Governor Donald Carcieri ignited Rhode Island’s Medicaid reform and won people over with a compelling case: His proposals did not deny people care, but targeted care at different groups’ needs. For example, when asked if people would be denied coverage, Gary Alexander, secretary of Rhode Island’s Office of Health and Human Services at that time, replied, “If there is an elderly population that needs podiatry, we want to be able to offer it to them, rather than to the entire population.”[9]

Liberal Democrats in Rhode Island were skeptical but went along with the plan because of its popularity. With political momentum on their side, Carcieri and Alexander were able to get a large coalition on board. Thus, the major challenge for state legislators was not Republicans versus Democrats, but Rhode Island versus federal agencies handling the state’s waiver.

TennCare of 1993

TennCare dates back to June 1993, when then-Governor Ned McWherter and the Tennessee Department of Health applied for a Medicaid waiver. The main objective was to shift Tennessee’s Medicaid program from public provision to man- aged care organizations. McWherter sought rapid approval due to concern over pushback from the Tennessee Medical Association.[10] The savings from the shift would be used to expand coverage to the uninsurable and non-poor uninsured groups.

Tennessee’s reforms promised cost savings and were viewed as a radical new approach to Medicaid. However, the rapid implementation led to great confusion about care and weakened McWherter’s overall base. People were suddenly told their traditional means of health care was shifting and policies were not in place to get their questions answered. The Tennessee Medical Association took a strong position against the reforms due to the low capitation rates.

By 2000, the plan was viewed as a failure. By shifting cost savings to uninsured groups, the system faced constant demand-side pressure and never reduced taxpayers’ costs. The low capitation rates, the lowest in the country for some time, reflected the state’s failure to appropriately price risk. In essence, an adverse selection problem confronted TennCare: eligibility was expanded without concomitant increases in capitation rates. As the Tennessee Medical Association warned, poor pricing led to major increases in expenditures.[11]

Washington State’s SB 5596 of 2011

Washington State’s 2011 Medicaid reform authorized greater flexibility and a block-grant-like approach to funding. While time will tell, the general tenor of the reforms and the block-grant style, which cap expenditures and encourage innovation, are reasons for optimism.

Unlike Tennessee’s program, which was six months in the making, Washington spent six years building consensus and calculating the best reforms. Governor Chris Gregoire developed a commission tasked with recommending reforms “for Washingtonians by Washingtonians.”[13] After years of careful study, the commission submitted recommendations for reform. By taking enough time and working to overcome the concerns of interest groups and the opposition, Gregoire succeeded in getting a radical-looking reform bill passed.While time will tell, the general tenor of the reforms and the block-grant style, which cap expenditures and encourage innovation, are reasons for optimism.

RECOMMENDATIONS

If cost-saving reforms are necessary, and do not compromise well-being, what blocks their passage? Politics. Politics can kill the best of ideas. Reforms in Tennessee and Florida were radical in scale and scope. But they were not as successful as reforms in Rhode Island and Washington because they were rushed and stakeholders were less engaged. Reformers must work to bring key interest groups—even opponents—into discussions. Skeptics can provide input while gaining an understanding of the seriousness of the fiscal problems.

Rhode Island and Washington have, in effect, implemented block-grant reforms. Yet, political leaders there do not make a big deal about the radical nature of their reforms, nor do they want their reforms to be called “block grants” due to negative connotations. Reformers who consider the impact of their words and actions on their opponents are more likely to succeed.

Tennessee’s reforms are an example of bad messaging: Tennessee’s attempted reforms lacked the buy-in needed for long-term success. In contrast, Rhode Island and Washington’s leaders didn’t fixate on ideological purity. Their actions spoke louder than words.

CONCLUSION

Many states are initiating their own experiments with radical Medicaid reform. New York and Utah are both pursuing cost-saving reforms to shift Medicaid participants to privately run managed care plans. By incorporating lessons from other states, policy makers should be able to save time, build greater consensus, and deliver more effective Medicaid services to participants at a lower cost to taxpayers.

Footnotes

1. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, “Fiscal Year 2010 Bud- get in Brief: Medicaid,” HHS.gov, 2011, http://dhhs.gov/asfr/ob/ docbudget/2010budgetinbriefm.html; The National Association of State Budget Offices, “State Expenditure Report,” NASBO.org, 2011, http:// www.nasbo.org/sites/default/files/2010%20State%20Expenditure%20 Report.pdf.

2. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, “Medicaid Enroll- ment: December 2010 Snapshot,” December 20, 2011, http://www.kff. org/medicaid/enrollmentreports.cfm; Kathleen Gifford et al., A Profile of Medicaid Managed Care Programs in 2010: Findings from a 50-State Survey (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Unin- sured, 2011), http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/8220.pdf. CMS data came from CMS, National Health Expenditure Projections 2010– 2020 (Washington, DC: CMS, 2010), https://www.cms.gov/National- HealthExpendData/downloads/proj2010.pdf.

3. Tarren Bragdon, Florida’s Medicaid Reform Shows the Way to Improve Health, Increase Satisfaction, and Control Costs (Washington, DC: Heritage Foundation, 2011), http://www.floridafga.org/wp-content/ uploads/Combined-Medicaid-Reform-Pilot-Nov-2011.pdf. Bragdon estimates $28.6 billion in savings for the United States as a whole if all 50 states embraced the Florida model.

4. See Joan Alker and Jack Hoadley, Understanding Florida Medicaid Today and the Impact of Federal Health Care Reform (Washington, DC: Health Policy Institute at Georgetown University, 2011), http://hpi.georgetown. edu/floridamedicaid/pdfs/Health_Reform_FL_2011.pdf. See also Alker and Hoadley, As Legislators Wrestle to Define Next Generation of Florida Medicaid, Benefits of Reform Effort Are Far from Clear (Washington, DC: Health Policy Institute at Georgetown University, 2011), http://hpi. georgetown.edu/floridamedicaid/pdfs/Medicaid_Reform_FL_2011. pdf.

5. Joan Alker, Jack Hoadley, and Jennifer Thompson, Florida’s Experience with Medicaid Reform: What has Been Learned in the First two Years? (Washington, DC: Health Policy Institute at Georgetown University, 2008), http://hpi.georgetown.edu/floridamedicaid/pdfs/briefing7.pdf.

6. Center on Disabilities and Human Development (CDHD), Issue Brief: Federal Approval of Idaho Medicaid Reform (Moscow, ID: CDHD, 2006), http://www.idahocdhd.org/Portals/44/docs/federal-approval- of-idaho-medicaid-reform.pdf.

7. National Association of Social Workers, “Lawmakers so far like Medicaid plan...” The Gatekeeper, November 2005 (reprint from Idaho Statesman, October 30, 2005), http://www.naswidaho.org/newsletter/The%20 Gatekeeper%2011-05.pdf.

8. John Graham, “In the Nick of Time: Rhode Island’s Medicaid Waiver Shows How States Can Save Their Budgets from Obamacare’s Assault,” Health Policy Prescriptions 9, no. 1 (San Francisco: Pacific Research Insti- tute, 2011), http://www.pacificresearch.org/publications/in-the-nick- of-time-rhode-islands-medicaid-waiver-shows-how-states-can-save- their-budgets-from-obamacares-assault. See also Benjamin Domenech, “The Rhode Island Medicaid Experience,” Reform + Medicaid, March 19, 2011, http://reformmedicaid.org/2011/03/the-rhode-island-medicaid- experience/.

9. John Buntin, “Ending Medicaid As We Know It,” Governing the States and Localities, June 2011, http://www.governing.com/topics/finance/ ending-medicaid-as-we-know-it.html.

10. Mark Ross Daniels, Medicaid Reform and the American States (West- port, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1998).

11. Adam Zaretsky, “Revamping Medicaid: A Five-Year Check-up on Ten- nessee’s Experiment,” The Regional Economist, Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis, 1999, http://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/re/ articles/?id=1751.

12. AP and WATE, “Bredesen scraps TennCare,” WATE News (Knox- ville, TN), November 10, 2004, http://www.wate.com/Global/story. asp?s=2547662.

13. Washington Governor’s Office, “Governor Gregoire Enacts Health Care Reforms,” news release, May 11, 2011, http://www.governor.wa.gov/ news/news-view.asp?pressRelease=1706&newsType=1.