- | Housing Housing

- | Policy Briefs Policy Briefs

- |

Property Tax Rates and Local Government Revenue Growth

Taxpayers and policymakers alike are drawing attention to opaque tax practices at the local level. Recent evidence suggests that local officials have the incentive to raise extra revenue through less transparent means and are channeling this revenue into assets for future spending. States have an opportunity to make their tax structure more transparent by adjusting tax rates following property reassessments and making the calculation of their property taxes clearer.

Transparency in tax systems is a widely valued policy principle because it helps voters understand the costs of the public services they receive. Some have accused politicians of deliberately obfuscating the tax system to hide the true costs of their spending programs. Transparency in taxation can aid the taxpayer who knows what to look for as a signal of cost. A prime example exists in local property taxes, which are widely regarded as transparent but are also commonly misunderstood. Other familiar taxes, like those on sales or income, require policymakers to set a tax rate first, which then produces revenue. Property taxes, by contrast, require policymakers to first determine the revenues to be raised, and then set a tax rate. This can cause property tax rates to be a misleading indicator of government cost, particularly when rising property values permit both lower tax rates and higher spending. Public policy should improve taxpayers’ understanding by directing their attention to both property tax rates and property tax revenues.

Truth in Taxation?

Government finances represent a complex system of excise taxes, intergovernmental aid, fees, assets, and debt. The best practices for representing and communicating government fiscal affairs are continually evolving and should be distinguished from financial management gimmicks designed to obscure governmental activity. Many states have adopted various “truth in taxation” laws and standardized accounting practices for their local governments to aid citizen monitoring of public finances. Many of these efforts are specifically targeted at the property tax, which is the largest source of local government revenue in the United States. Examples of these efforts to improve transparency include requirements to publish proposed budgets, special announcements when property taxes are to exceed a certain percentage in growth, and notices that property assessors do not determine tax bills.

In addition to being the main source of local government revenue, property taxes occupy significant attention for monitoring because of their unique role in the budgeting process. In most states, a local government will adopt a “property tax levy,” which is a fixed amount of revenue it wants to collect from owners of taxable property. Individual taxpayers contribute their share to the property tax levy according to their percentage share of total taxable property, which is determined in a process of property assessment. This results in a “property tax rate” that can be calculated by dividing the amount of revenue desired by local government by the total taxable property values. A new rate is determined every time a budget is adopted. Taxpayers are much more likely to be familiar with tax rates on sales or income, where changes to the rate involve considerable public debate and produce a revenue amount that is not predetermined.

If voters continue to focus on property tax rates as the signal of local government cost, the disconnect between property values and property tax revenues implies that property reassessments provide an opportunity for politicians to hide the growth of the public sector from citizens. A reassessment that results in increased property values would allow local politicians to spend more money while simultaneously keeping the rate unchanged or even lowering it, delivering the perception that they were able to both “cut taxes” and offer more services.

There is empirical evidence of this occurring at the local level in Florida, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Nebraska, and Virginia. This discussion will focus on the case of Virginia, using findings from a new study published by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University as its foundation. Although policymakers may employ deceptive methods to make taxes less visible, public concern has nevertheless risen in response. Citizens from Northern Virginia have expressed unease about what they consider to be “sneaky” tax increases—when property values rise, but tax rates are not lowered.

Analysis

The Commonwealth of Virginia requires local governments to adopt a property reassessment cycle ranging from one to six years. This institutional environment allows politicians to anticipate changes in property values and adjust their plans accordingly. Local officials may add more spending projects now if they know property values will rise in the next cycle and mask what would otherwise be a rising tax rate.

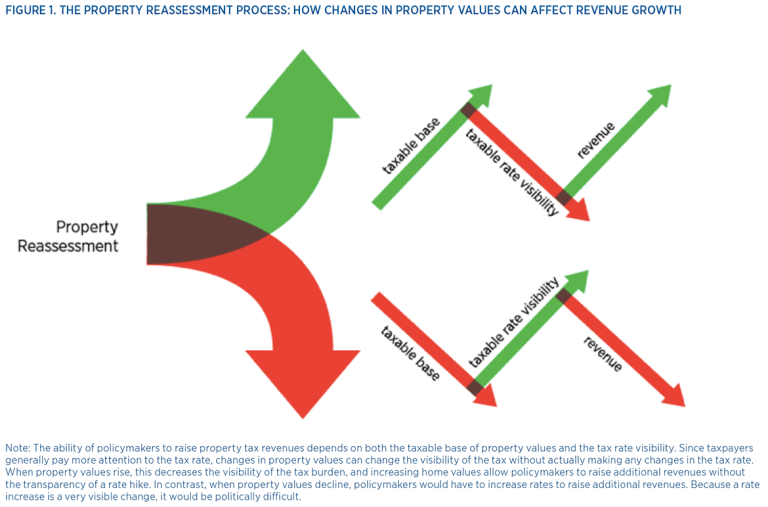

The fiscal consequences of this behavior are confirmed by Justin Ross in his recent study published by the Mercatus Center, “The Effect of Property Reassessments on Fiscal Transparency and Government Growth: Evidence from Virginia.” Ross finds that property reassessments in Virginia substantially increase public sector revenues through increases in the property tax. Figure 1 displays the two ways that this phenomenon can manifest.

Note: The ability of policymakers to raise property tax revenues depends on both the taxable base of property values and the tax rate visibility. Since taxpayers generally pay more attention to the tax rate, changes in property values can change the visibility of the tax without actually making any changes in the tax rate. When property values rise, this decreases the visibility of the tax burden, and increasing home values allow policymakers to raise additional revenues without the transparency of a rate hike. In contrast, when property values decline, policymakers would have to increase rates to raise additional revenues. Because a rate increase is a very visible change, it would be politically difficult.

The first is when a mass property reassessment takes place that increases the taxable base of property values. Because there is no corresponding decrease in the tax rate, this causes property tax revenues to grow significantly within the same year. Ross explains that this was able to occur in Virginia counties because they decreased the visibility of the property tax by hiding the levy increases.

The second scenario is when a mass property reassessment takes place that decreases the taxable base of property values. Ross found that property tax revenue grew significantly in the years leading up to such an assessment. In this scenario, the future property tax rates will increase even without new spending projects. Politicians are able to anticipate the increased attention to property tax rates and the additional difficulty of raising property taxes at that time. Using this information, politicians are incentivized to level up the property tax before the property reassessment, while the property values are still high. Both findings suggest that local officials intentionally take advantage of property reassessments in order to increase revenue.

Despite these revenue increases, there is evidence that this money is not being used for immediate spending projects. Ross finds a significant increase in nonrevenue receipts in the year following a reassessment. Nonrevenue receipts are any funds coming from nonrecurring sources such as rainy day funds, general fund reserves, or sales of property or other assets. When nonrevenue receipts increase following an assessment, this suggests that this channel is being used as a less visible source for funding spending projects. It can be inferred that the extra revenues raised from reassessments are funneled into nonrevenue receipts and withdrawn in the next year in order to avoid drawing attention to the funding sources. Policymakers engage in this behavior because they face incentives to overemphasize the benefits and de-emphasize the costs of government services.

Proposal

Virginia does not currently have laws to alleviate the problem of local officials increasing revenue through property reassessments, but several other states have implemented rules designed to reduce the opportunities for policymakers to use rising property values to increase tax revenue. Policies have been implemented to either limit the property tax rate adjustment or limit property tax revenues.

Pennsylvania has an “anti-windfall” provision that imposes a special limit on tax rate growth to prevent local governments from collecting additional revenues from rate adjustments. It requires municipalities to vote for any increase in the tax rate, and the increase must not exceed the previous year’s tax levy by more than 10 percent. Similarly, Louisiana’s “millage rollback” rule uses a formula to prevent excessive growth in the property tax rate. If the total assessed value of property in a locality increases, then the local government is required to decrease its tax rate to account for the extra revenue.

In addition to property assessment limits, policymakers can improve this situation by increasing transparency. This means clarifying the property tax calculation and the amount of revenue the tax produces. The good news is that property taxes are among the most visible type of taxes. It is through the reassessment process that the visibility of the property tax is being jeopardized. A complex tax system is not only misleading, it increases compliance costs as it becomes more difficult for taxpayers to understand. Choosing simpler and more visible tax instruments would help to alleviate these problems.

Conclusion

Taxpayers and policymakers alike are drawing attention to opaque tax practices at the local level. Recent evidence suggests that local officials have the incentive to raise extra revenue through less transparent means and are channeling this revenue into assets for future spending. States have an opportunity to make their tax structure more transparent by adjusting tax rates following property reassessments and making the calculation of their property taxes clearer. A more transparent tax structure allows for taxpayers to make more informed decisions about their desired level of government services.