- | Technology and Innovation Technology and Innovation

- | Policy Briefs Policy Briefs

- |

Reforming the FCC’s Low-Income Phone Subsidies

Historically, the FCC’s Universal Service Fund has paid for two programs that subsidize telephone service for low-income households. Lifeline, the larger program, pays phone companies to reduce monthly subscription fees for low-income households by an average of $9.25 per month, with some states providing additional funding. Link Up subsidizes one-time connection charges by up to $30.2 In 2012, the FCC voted to phase out Link Up.

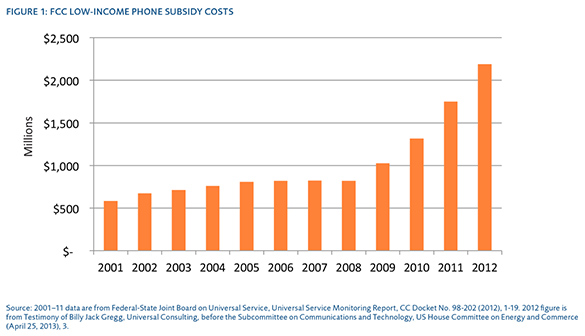

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) subsidizes phone service for low-income households, funded by the universal service charge assessed on all consumers’ phone bills. The cost of this program ballooned from $819 million in 2008 to $2.19 billion in 2012. Controlling costs while continuing to serve low-income households will likely require some combination of a reduction in the per-line subsidy, a program participation fee for all households, and a cap on the program’s budget.

The FCC's Low-Income Universal Service Program

Historically, the FCC’s Universal Service Fund has paid for two programs that subsidize telephone service for low-income households. Lifeline, the larger program, pays phone companies to reduce monthly subscription fees for low-income households by an average of $9.25 per month, with some states providing additional funding.1 Link Up subsidizes one-time connection charges by up to $30.2 In 2012, the FCC voted to phase out Link Up.

General federal tax revenues do not fund these subsidies. Instead, the FCC assesses a “contribution factor” on phone companies’ interstate and international revenues. Though not called a tax, the contribution factor acts like a percentage tax on wired and wireless phone companies’ revenues. Phone companies generally break out universal service charges as a separate line item on customers’ bills. In 2012, the contribution factor averaged approximately 17 percent.3 If the cost of any universal service program changes substantially, the FCC adjusts the contribution factor, and the size of the universal service charge on phone bills changes.

As Figure 1 shows, low-income phone subsidies have more than doubled since 2008, rising from $819 million in 2008 to $2.19 billion in 2012.

Why Low-Income Phone Assistance Grew

The total cost of the low-income universal service programs grew for four main reasons: (1) the recession created more eligible households, (2) wireless carriers brought in new low-income subscribers, (3) waste, fraud, and abuse inflated costs, and (4) absence of a budget-cap–delayed prioritization.

1. The recession created more eligible households. Figure 2 compares the number of Lifeline subscribers and Link Up beneficiaries with the number of participants in the Agriculture Department’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) during the past decade. They follow roughly the same pattern, with a pronounced upward trend starting after the recession of 2008. The number of SNAP beneficiaries appears to increase at a more rapid rate than Lifeline and Link Up beneficiaries because each member of a household is counted as a SNAP beneficiary, whereas Lifeline and Link Up are supposed to be limited to one subsidy per household.

2. Expansion of the low-income program to new types of wireless carriers brought in new subscribers. The FCC first authorized low-income subsidies in 2005 for “non-facilities-based” wireless carriers.4 (Non-facilities-based wireless carriers are wireless companies that lease capacity on the major carriers’ networks instead of building their own.) In 2005, incumbent wireline phone companies received $735 million in low-income subsidies, and competitive carriers (both wireless and wireline) received $68 million. By 2011, the competitive carriers’ subsidies had grown more than 18-fold, to $1.2 billion, while the wireline incumbents’ subsidies fell to $558 million.

Part of this change reflects the general consumer shift from wired to wireless phones in recent years. But it also reflects the fact that low-income wireless service with a basic package of minutes is usually free to the subscriber, rather than just discounted. Faced with a choice between free wireless service or discounted wireline service, many low-income households quite sensibly pick the free service.