- | Regulation Regulation

- | Working Papers Working Papers

- |

Regulating Automobiles: The Consequences for Consumers

Automobiles are ubiquitous. Most Americans take at least one car trip every day to get to work or school or to run household errands. The automobile has also never been safer. New technology has brought car frames that crumple to reduce the impact of a crash, airbags that cushion the blow of an accident, and cameras that show drivers what is behind the vehicle. In addition, rising standards of living have allowed consumers to purchase more safety equipment and to question the environmental impact of cars. While cleaner, safer automobiles certainly have benefits, as economists, we must ask, what do all these regulations cost the consumer? Costs arise from three sources: workplace safety regulation, environmental regulation, and consumer safety regulation. In this paper, we examine each area in turn, focusing on how the cost of regulations impacts the average automobile consumer.

A popular argument for regulation holds that leaving consumers and manufacturers to their own devices would lead to undesirable outcomes. First, in seeking to maximize profits, manufacturers may deceive customers into believing cars are safer than they actually are, and they might reduce manufacturing costs by sacrificing safety. Second, because both manufacturers and consumers are seeking the best deal for themselves, they may impose costs on third parties not involved in the transaction. For example, a buyer might wish to purchase a less expensive car that has poor environmental performance, rationalizing that one car, among the many thousands in the immediate area, can have no real impact on the environment.

The first scenario involves unethical and illegal business practices. The second is a classic public goods problem resulting in negative externalities. While these problems may be classic market failures that necessitate government intervention, the regulations purporting to provide solutions come at a cost. While regulations perhaps impose that cost more directly on the manufacturer, the consumer ultimately bears it, at least in part, in the form of higher prices.

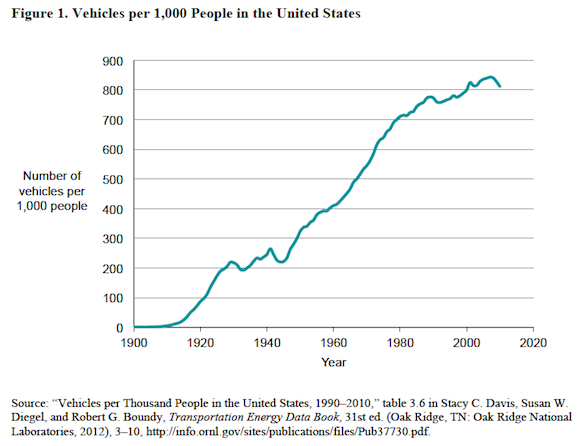

Automobiles have served pivotal roles in Americans’ lives throughout the past century. Although initially only the wealthiest individuals owned automobiles, Henry Ford’s mass production of automobiles in the early 20th century made them affordable for less wealthy families.1 The affordability and convenience of automobiles, along with their relative cleanliness, led them to quickly replace horses as the dominant mode of transportation in the United States. In 1920 Americans owned twice as many horses as automobiles, but by 1930 they owned twice as many automobiles as horses.2 By 1927 half of American families owned at least one automobile and by 1970 that number had grown to 83 percent.3 Figure 1 shows the increasing prevalence of automobiles in the United States over the past century, as the number of automobiles per 1,000 Americans increased from less than one in the early 1900s to more than 800 today.