- | Government Spending Government Spending

- | Data Visualizations Data Visualizations

- |

The Ryan-Murray Budget Plan: More of the Same

On December 10, 2013, Senate Budget Committee chairwoman Patty Murray and House Budget Committee chairman Paul Ryan revealed the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013. Coming after partisan gridlock and political incentives prevented Congress from enacting a constitutionally required budget for almost half a decade, the Ryan-Murray budget promises action through compromise. A comparison of the Ryan-Murray plan to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) baseline shows that this proposal is heavy on compromise and light on real reform.

On December 10, 2013, Senate Budget Committee chairwoman Patty Murray and House Budget Committee chairman Paul Ryan revealed the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013. Coming after partisan gridlock and political incentives prevented Congress from enacting a constitutionally required budget for almost half a decade, the Ryan-Murray budget promises action through compromise. A comparison of the Ryan-Murray plan to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) baseline shows that this proposal is heavy on compromise and light on real reform. This week’s charts use data from the CBO score of the Ryan-Murray budget plan and the CBO’s updated baseline and alternative budget projections to compare outlays, revenues, and deficit projections under the Ryan-Murray proposal to those under the CBO baseline for the next ten years. The charts show that the Ryan-Murray budget plan barely changes the status quo—and may in fact make fiscal problems worse.

This week’s charts use data from the CBO score of the Ryan-Murray budget plan and the CBO’s updated baseline and alternative budget projections to compare outlays, revenues, and deficit projections under the Ryan-Murray proposal to those under the CBO baseline for the next ten years. The charts show that the Ryan-Murray budget plan barely changes the status quo—and may in fact make fiscal problems worse.

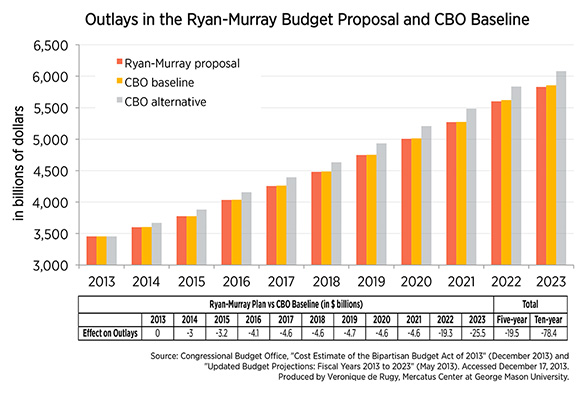

The first chart displays proposed outlays under the Bipartisan Budget Act to the CBO baseline and alternative projections. The alternative fiscal scenario is a more sober, and arguably more realistic, projection of the US fiscal position. The chart shows that the Ryan-Murray plan just barely differs from the status quo. In exchange for $63 billion in repealed sequestration cuts, the Ryan-Murray plan aims to balance the difference with escalating spending cuts, which are slight and concentrated at the end of the next decade. For instance, the Ryan-Murray budget spends $19.3 billion less than the CBO baseline by 2022. In 2023, these outlay savings will “surge” to $25.5 billion for that fiscal year. All told, the Ryan-Murray plan stretches a skimpy $78.2 billion in decreased relative spending over a decade, for an average of $7.1 billion per year. After factoring in the increased short-term spending wrought by the diminished sequestration, decreased spending in the Bipartisan Budget Act is only $15.2 billion over the next decade.

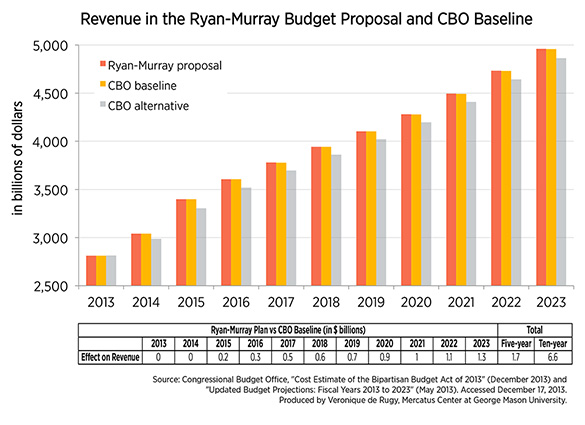

The second chart compares revenue changes in the Bipartisan Budget Act to the CBO baseline. The differences here, too, are virtually indistinguishable. The Ryan-Murray plan does not raise taxes, but projects that revenues will increase through the magic of “controlling waste, fraud, and abuse.” Revenues are projected to increase by less than $1 billion each fiscal year from 2014 to 2020 before increasing by $1 billion in 2021, $1.1 billion in 2022, and $1.3 billion in 2023. The Ryan-Murray proposal projects revenues exceeding the CBO baseline by $6.6 billion over a decade; however, Sen. Murray and Rep. Ryan have been adamant that their proposal is focused on spending changes, so it is not surprising that their revenue projections are modest.

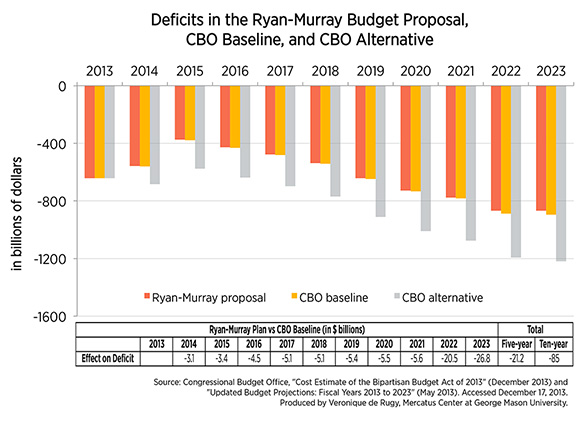

The second chart compares revenue changes in the Bipartisan Budget Act to the CBO baseline. The differences here, too, are virtually indistinguishable. The Ryan-Murray plan does not raise taxes, but projects that revenues will increase through the magic of “controlling waste, fraud, and abuse.” Revenues are projected to increase by less than $1 billion each fiscal year from 2014 to 2020 before increasing by $1 billion in 2021, $1.1 billion in 2022, and $1.3 billion in 2023. The Ryan-Murray proposal projects revenues exceeding the CBO baseline by $6.6 billion over a decade; however, Sen. Murray and Rep. Ryan have been adamant that their proposal is focused on spending changes, so it is not surprising that their revenue projections are modest.  The final chart displays deficit projections under the CBO baseline, Ryan-Murray budget proposal, and the CBO’s alternative fiscal scenario, which projects budget data assuming that no fundamental reform occurs in the interim. The chart shows that deficits under the Ryan-Murray budget proposal are a slight improvement over baseline deficits, and the alternative fiscal scenario is still larger. What’s more, the Ryan-Murray deficit reductions assume that planned spending cuts toward the end of the decade will actually take effect. Given that the Bipartisan Budget Act itself overturned the previously planned future spending cuts of the sequestration, this is a dubious assumption.

The final chart displays deficit projections under the CBO baseline, Ryan-Murray budget proposal, and the CBO’s alternative fiscal scenario, which projects budget data assuming that no fundamental reform occurs in the interim. The chart shows that deficits under the Ryan-Murray budget proposal are a slight improvement over baseline deficits, and the alternative fiscal scenario is still larger. What’s more, the Ryan-Murray deficit reductions assume that planned spending cuts toward the end of the decade will actually take effect. Given that the Bipartisan Budget Act itself overturned the previously planned future spending cuts of the sequestration, this is a dubious assumption.

Taken together, these charts suggest that even in the best possible scenario, the Ryan-Murray budget plan does not do much to change the status quo. Even if we accept the unrealistic premise that policymakers can keep their promises to cut spending in the future, the Ryan-Murray budget plan would be a mere drop in the bucket of the US government’s fiscal problems. The Bipartisan Budget Act does not even touch some of the biggest drivers of federal debt and spending—entitlement programs like Medicare and Social Security. What’s more, public choice theory and recent political history suggest that there is a good chance that the repealed sequestration cuts will not be paid for by future spending cuts. The Ryan-Murray budget is ultimately a counterproductive distraction that allows policymakers to feel like they are doing something while our country continues to sink deeper into the red. Until policymakers sober up and face the need for fundamental entitlement reform, these “bipartisan” do-nothing budget proposals should be scrutinized for what they really are: rearranging the deckchairs on the Titanic.