- | Financial Markets Financial Markets

- | Policy Briefs Policy Briefs

- |

Speed Bankruptcy as the TARP Alternative

Policymakers continue to seek viable alternatives to resolve large insolvent financial institutions. A better option is speed bankruptcy: a process of converting some long-term debt into equity, a

In the fall of 2008, the U.S. government invested hundreds of billions of dollars in the nation's banks through the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). At the time, policy makers, both Republican and Democrat, claimed that this was the only practical way to save the banking sector. Without massive government purchases of equity shares in the big banks, they alleged, the financial sector—and with it, the real economy of paychecks, jobs, and profits—would collapse.

Congress did, however, have another option: It could have given the FDIC power to initiate speed bankruptcy when major financial institutions are in trouble. Speed bankruptcy, also known as debt-to-equity swaps or prepack bankruptcy, is essentially the rapid conversion of bonds into equity. This option, which was supported by prominent academic economists,1 would have made the banks healthier by breaking promises to bondholders. Speed bankruptcy could become the path forward as Congress decides how to deal with future financial crises.

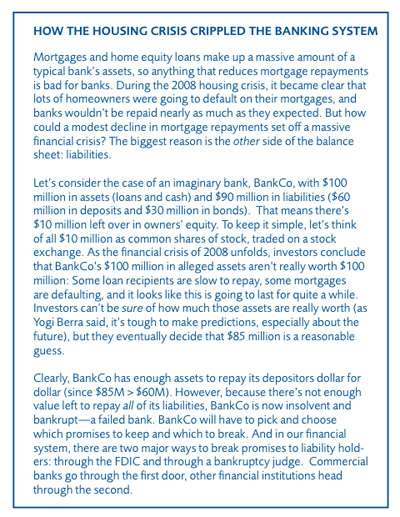

A BANK'S BALANCE SHEET

To understand how speed bankruptcy works, we first need to consider what makes a bank healthy. Let's begin with the old accountant's truism, the balance sheet identity:

Assets = Liabilities + Owner's Equity

This means that "what you own" (assets like land, machines, and money that other people owe you) equals "what you owe" (liabilities like money you owe to others) plus whatever is left over. In a healthy company, assets are much higher than liabilities—the company has a promising future and has few debt promises to repay—so there's a lot of value left over for the owners. When assets fall below liabilities, the company is insolvent.

For a bank, assets mostly refer to loans, financial investments, and the value of the bank's branches and offices—all the things that the bank could, in a pinch, sell to other companies to raise money. A bank's liabilities fall into two major categories: deposits and bonds. A bank deposit is funds put into a customers' account for safekeeping, to be retrieved at a later date, while a bond is simply an IOU, a note to a customer promising that a specific amount of money will be repaid to the customer at a given time.2 In both cases, the bank owes a fixed number of dollars to someone in the future. So buying a bond is a lot like depositing money in a bank, with one major exception: Though the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) rarely guarantees bank bonds, it guarantees most bank deposits with the full faith and credit of the U.S. government.

The FDIC will typically take over a bank that is insolvent. During this process, depositors' funds are typically untouched since they are insured by the FDIC, and the FDIC sells the banks to new owners. The bank's old bondholders get repaid with the proceeds of the bank sale. This speed bankruptcy process can occur in a matter of days, as it did with two large bank holding companies, Washington Mutual and FBOP. Using a similar mechanism, General Motors emerged after 40 days, marking the fourth-largest filing in U.S. history.3 So while the process can be rapid, there's a widespread misperception that bankruptcy must, by definition, take months or years, a process that was considered too lengthy during the 2008 financial crisis.

WHAT ABOUT THE BIGGEST BANKS?

FDIC-initiated speed bankruptcy seems to work well with some large banks, but what about Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and other financial behemoths? For instance, the liability side of Citigroup's balance sheet is roughly $2 trillion. And of that amount, only about $700 billion are made up of deposits, while the rest includes bondsand other financial obligations. How can speed bankruptcy work for institutions this large?

The answer lies in the difference between $2 trillion and $700 billion (the latter are largely guaranteed by the FDIC). The central tenet of speed bankruptcy is slashing away at liabilities in order to get to a point where:

Assets > Liabilities

The FDIC (or a bankruptcy judge) can quickly reduce liabilities by informing bondholders that they will receive less than they thought. Once assets are greater than liabilities, the firm has enough value for it to function well in the future. As for the bondholders' plight, Luigi Zingales of the University of Chicago4 has offered a straightforward solution: Convert the mega-bank's debt into equity; convert bonds into stock. This might sound like a late-night infomercial promising to "transform debt into wealth," but it's nothing of the sort. Instead, it's a way of giving a consolation prize to bondholders without the need for the FDIC to search for a new buyer. Instead, the FDIC can just turn the old bondholders into new shareholders.

RELIVING THE PAULSON PANIC

Instead of asking Congress for $700 in TARP funding, Secretary Paulson and Chairman Bernanke should have recommended a few modest changes in U.S. bankruptcy code.5 These changes entail giving a bankruptcy judge or the FDIC the authority to convert bank bonds into new shares of common stock in the same bank. This power wouldn't change the rules of the game—after all, such "debt-to-equity conversions" are a routine, even expected part of bankruptcy—but they would clarify that the judge or the FDIC would have power to make such decisions quickly and with little interference when large, systemically important financial institutions are involved.

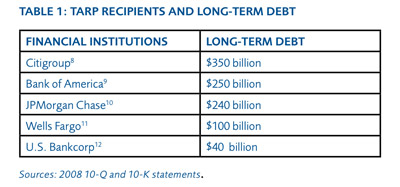

After Congress enacts the new speed bankruptcy legislation— perhaps giving resolution power to FDIC—then the speed bankruptcies commence.6 It would be both wise and fair to convert long-term debt (10 years plus) into equity before doing so for short-term debt—after all, short-run debt is a key source of liquidity in financial markets, and long-term debt is always considered higher risk than short-term debt.7 Interestingly, in 2008 there was enough long-term debt on the books of the nation's mega-banks. The five biggest recipients of TARP funding collectively held over $1 trillion in long-term bond liabilities on their balance sheets, more than the total TARP bill itself (see table 1).

If the new shareholders don't want to be shareholders, they are entirely free to sell their new shares to other investors. They can go from being bondholders to being partially-repaid former bondholders within a matter of days. And by letting bondholders know that they really can lose money when they buy bank bonds, the FDIC will encourage bondholders to monitor the health of America's banks more carefully in the future.13

SPEED BANKRUPTCY AS A PATH FORWARD

Congress is considering new "resolution authorities" that would give the FDIC power to enact some form of speed bankruptcy when big banks get into trouble.14 As this Mercatus on Policy has shown, speed bankruptcy—FDIC-mandated conversion of bonds into common stock—could have rebuilt our banking system without spending a dollar of taxpayer money. In fact, the Bush Treasury considered the possibility of speed bankruptcy, but decided it was politically impossible. Philip Swagel, a Treasury economist at the time, later noted,

The simple truth is that it was not feasible to force a debt for equity swap or to rapidly enact the laws necessary to make this feasible. To academics who made this suggestion to me directly, my response was to gently suggest that they spend more time in Washington, DC.15

What was "not feasible" in the fall of 2008 is now being debated in the halls of Congress. One can only hope that political reality has changed to reflect the economic reality: Speed bankruptcy works.

ENDNOTES

1. See Joseph Stiglitz, "A Bank Bailout that Works," The Nation, March 4, 2009, http://www.thenation.com/doc/20090323/stiglitz, and Luigi Zingales, "Plan B," The Economists' Voice 5, no. 6 (October 2008), http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/luigi.zingales/research/papers/plan_b.p….

2. For example, an investor might purchase a one-year, $10,000 bond, which means that the investor will pay the bank $9,500 with the expectation of receiving $10,000 after one year.

3. John D. Stoll and Sharon Terlep, "GM Takes New Direction," The Wall Street Journal, July 11, 2009, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124722154897622577.html.

4. Luigi Zingales, "Why Paulson is wrong: Saving capitalism from capitalists," VOX, Center for Economic Policy Research, September 21, 2008, http://www.voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/1670.

5. See Luigi Zingales, "How to Fix the Credit Mess Without a Government Bailout: Quickie Bankruptcies," October 27, 2008, http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/luigi.zingales/research/papers/forbes_h…. Also, there are minor changes that would be needed—the rules regarding derivatives clearing are a prime barrier to speed bankruptcy.

6. The House of Representatives has passed new legislation that would encourage speed bankruptcies, by giving regulators authority to force major financial institutuions to issue bonds that convert into shares in a financial crisis. Section 1116 of HR 4173 states that regulators can force major firms to issue: "long-term hybrid debt that is convertible to equity when...the [U.S. government] determines that a specified financial company fails to meet prudential standards...threats to United States financial system stability make such a conversion necessary."

7. The Economist, Guide to Economic Indicators: Making Sense of Economics, Fifth Edition (Princeton, New Jersey: Bloomberg Press, 2003), 181.

8. Citigroup's 2008 Annual Report on Form 10-K, February 2008, http://www.citigroup.com/citi/fin/data/k08c.pdf?ieNocache=892.

9. Bank of America's SEC 10-K filing, February 2008, http://investing.businessweek.com/research/stocks/financials/drawFiling….

10. JPMorgan Chase, SEC 10-K filing, February 2008, http://investing.businessweek.com/research/stocks/financials/drawFiling….

11. Wells Fargo & Company, SEC 10-K filing, February 2008, https://www.wellsfargo.com/downloads/pdf/invest_relations_2008_10k.pdf.

12. U.S. Bancorp, SEC 10-K filing, February 2008, http://investing.businessweek.com/research/stocks/financials/drawFiling….

13. Charles Calomiris, "Blueprints for a New Global Financial Architecture," October 7, 1998, http://www.house.gov/jec/imf/blueprnt.htm. He argues that subordinated debt holders would be a conservative force for restricting bank risk-taking.

14. HR 4173 makes this an option for regulators, not a requirement—so even if HR 4173 is enacted, speed bankruptcy will be only a possibility, not a reality.

15. Philip Swagel, "The Financial Crisis: An Inside View," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 38, http://www.brookings.edu/economics/bpea/~/media/Files/Programs/ES/BPEA/….