- | Government Spending Government Spending

- | Data Visualizations Data Visualizations

- |

Update: Social Security Remains on an Unsustainable Path

This week's charts use new data from the recently released 2014 Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance (OASDI) Trustees Report to update a previous Mercatus Center chart series presenting projected cash flows and worker-to-beneficiary ratios for Social Security programs.

This week's charts use new data from the recently released 2014 Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance (OASDI) Trustees Report to update a previous Mercatus Center chart series presenting projected cash flows and worker-to-beneficiary ratios for Social Security programs. As these charts show, the outlook for Social Security remains bleak. The system has run cash deficits for several years now and is projected to remain in the red for the foreseeable future. As the ratio of retirees to workers continues to increase and the probability that the program will be sustainable in the future continues to decrease, the need for reform becomes pressing.

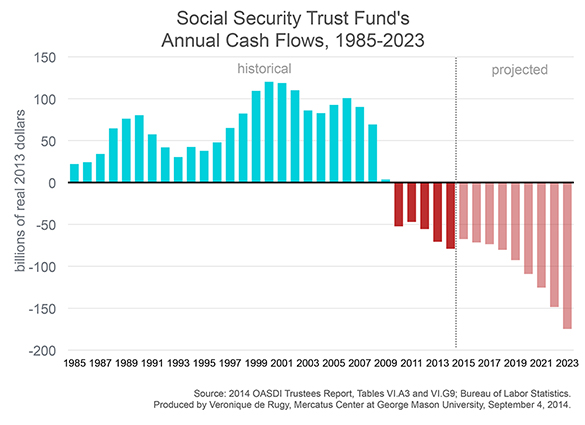

The first chart compares the trust fund’s historical balances since 1985 with annual balances projected under the trustees’ most realistic scenario, called “intermediate assumption” in the report, through 2023. The second chart displays the long-term trust fund balances projected under this realistic scenario, as well as high-cost and low-cost alternative assumptions through 2090. The final chart compares the historical worker-to-beneficiary Social Security ratios to the anticipated number of workers needed to support one Social Security retiree through 2090.

Since 2010, the Social Security program has been running a permanent cash-flow deficit, as the first chart shows. This means that the taxes collected during the year for the program fall short of what is needed to cover the benefits paid out to retirees. The program draws from the Social Security trust fund to fill the gap (first using the interest, then the principal) to maintain promised level of benefits to retirees. When this option is also insufficient, the US Treasury will have to start borrowing to pay out benefits.

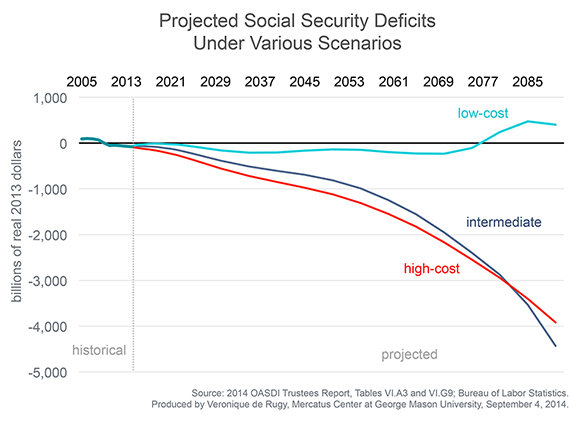

The OASDI trustees report contains three projections of Social Security deficits based on different methodological assumptions. The more realistic, or “intermediate,” scenario serves as a baseline that “reflect[s] the Trustees’ best estimates of future experience[s]” with key demographic, economic, and programmatic factors. The high-cost and low-cost scenarios provide brackets for a range of alternative experiences.

The second chart displays the intermediate projections along with the low-cost and high-cost projections through 2090. The intermediate scenario, which reflects the trustees’ most realistic expectations for the future, tracks closely with the high-cost scenario, eventually exceeding the high-cost deficits by 2090. The optimistic low-cost scenario projects moderate deficits of less than $250 billion until eventually returning to solvency by 2080. Unfortunately, the low-cost scenario is highly unlikely. The true path of Social Security deficits will most likely resemble the intermediate and high-cost scenarios.

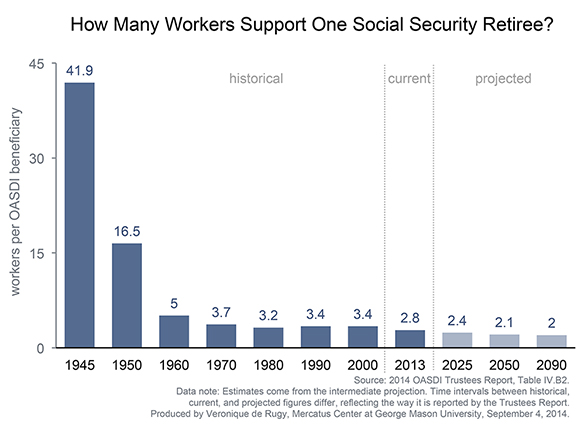

The third chart displays the number of workers it took to support one Social Security retiree for selected years since 1945, along with the intermediate projections for future dates. The burden of funding Social Security benefits has rested on fewer and fewer shoulders as the program has matured. In the early stages of the program, many paid in and few received benefits, and the revenue collected greatly exceeded the benefits being paid out. The program’s apparent advantage was misleading. Between 1945 and 1970, the decline in worker-to-beneficiary ratios went from 41 to four workers per beneficiary.

The Social Security program matured in the 1960s, when Americans were consistently having fewer children and living longer than previous generations. As these trends have continued, today there are just 2.8 workers per retiree—and this amount is expected to drop to 2.1 workers per retiree by 2050.

The program was stable when there were more than three workers per beneficiary. However, future projections indicate that the ratio could continue to fall to less than one worker per beneficiary, at which point the program in its current structure becomes financially unsustainable.

The OASDI trustees predict that the Social Security trust fund asset reserves will become depleted in 2033 and that the OASI Trust Fund will become insolvent in 2034. The longer that we wait to enact needed reforms to these entitlement programs, the more painful the adjustment needed in the future.