- | Government Spending Government Spending

- | Expert Commentary Expert Commentary

- |

A Guide to the 2014 Medicare Trustees Report

The Medicare report continues to show that program finances are on an unsustainable long-term trajectory largely due to demographic change, placing rising pressure on the federal budget and requiring legislative corrections, despite favorable adjustments to recent and projected rates of Medicare spending growth.

My last piece summarized the trustees' 2014 Social Security report, which can be found here. This piece presents highlights of this year's Medicare report. A summary of both reports can be found here, and video of our press conference here.

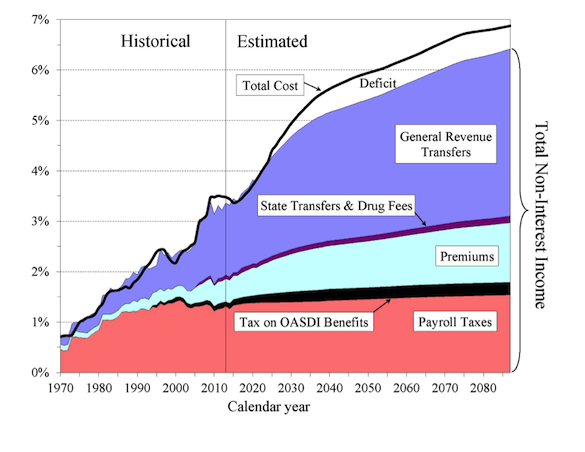

Medicare Has Different Components Financed in Different Ways

Each year there is enormous (I would say excessive) press interest in the projected date of depletion of Medicare's Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund. This fund represents but one part of Medicare, and less than half of program spending at that ($266 billion in 2013). Payments for physician services (Part B) as well as prescription drugs (Part D) are made from Medicare's Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) trust fund ($317 billion spent in 2013). SMI is kept solvent by statutory design; only about one-quarter of its revenues are provided by beneficiary premiums, the other three-quarters provided from the government's general fund in whatever amounts are necessary to finance benefits. Thus for the majority of Medicare, solvency is not a meaningful concept. Medicare's financial strains are not principally manifested in the threat of trust fund depletion but in rising pressure on the federal budget and on premium-paying beneficiaries.

There are other reasons why excessive attention to the projected HI trust fund depletion date (2030 in this report) is inadvisable. One is that the date is extremely sensitive to slight changes in the assumed rate of Medicare spending growth. This year we assumed a slower rate of future cost growth and so the date moved out from 2026 to 2030. In the 2011 report it went five years the other way, from 2029 to 2024. This variability exists in large part because the HI fund is not sitting on an enormous buildup of assets in the manner of the Social Security trust funds; at the start of this year the HI fund's assets were less (76 percent) than one year's costs. This percentage is down from 83 percent at the start of 2013. With such an insignificant trust fund balance it does not take much of a nudge in either direction to move the depletion date by several years. For example, if temporary sequestration under the Budget Control Act were overridden, the date would move closer again from 2030 to 2028.

Medicare is in Better or Worse Shape than Social Security Depending on One's Perspective

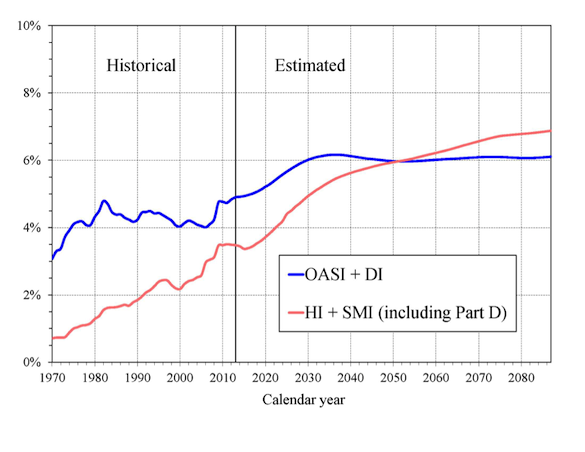

Viewed from a narrow trust fund perspective, Social Security is in worse shape than Medicare; it faces the larger actuarial imbalance as well as the earliest threat of trust fund depletion (its DI fund, in 2016). Looked at from a broader budget perspective, Medicare poses the greater challenge. Its costs are rising faster than Social Security's and will put greater pressure on the overall federal budget in the years ahead. Total Medicare costs are 3.4 percent of GDP today but are projected to rise rapidly to 5.4 percent of GDP by 2035, and 6.9 percent by 2088.

Projected Social Security (OASI + DI) and Medicare (HI + SMI) Costs as a Percentage of GDP Together, $272 billion will flow from the federal government's general fund to Medicare's HI and SMI trust funds in 2014. Medicare's rising costs will create still greater budgetary pressure in the upcoming decades.

Together, $272 billion will flow from the federal government's general fund to Medicare's HI and SMI trust funds in 2014. Medicare's rising costs will create still greater budgetary pressure in the upcoming decades.

Medicare Cost and Non-Interest Income by Source as a Percentage of GDP As with Social Security, Demographics are the Greatest Challenge Facing Medicare

As with Social Security, Demographics are the Greatest Challenge Facing Medicare

Medicare's costs will rise most rapidly through the mid-2030s as the baby boomers join the beneficiary rolls. From the report: "While every beneficiary in 2013 had about 3.2 workers to pay for his or her HI benefit, in 2030 under the intermediate demographic assumptions there would be only about 2.3 workers for each beneficiary." After the boomers finish swelling the rolls, total spending growth tails off a bit, though still growing faster than GDP from the 2030s onward because of rising benefit costs per capita.

Leading up to the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and afterward, our public discussion suffered from inadequate acknowledgment that for several decades to come Medicare's cost growth is driven more by demographics than by healthcare cost inflation. It was too tempting for advocates to suggest that our fiscal course could be corrected by painlessly making healthcare delivery more efficient through healthcare reform, rather than to confront the harder--yet more important--decisions as to how many people should receive subsidized health benefits, and for how much of their lives. Today there continues to be disproportionate emphasis on healthcare cost inflation when demographics have long been known to be the bigger factor well into the future.

This Year the Trustees Began to Emphasize a New Projected Baseline

The trustees' reports have long emphasized a scenario that differs in one critical respect from actual law. Under law, benefit payments would be curtailed at the point that Medicare's HI trust fund is depleted. Nevertheless the preponderance of the report has always shown the cost of paying full scheduled benefits. This is done because otherwise the report would assume that "imbalances between payments and revenues would be automatically eliminated, and the report would not serve its essential purpose, which is to inform policy makers and the public about the size of any trust fund deficits that would need to be resolved to avert program insolvency."

This year for the first time our report emphasizes a scenario that differs from current law in another important respect, namely that a 21 percent reduction in Medicare physician payments now scheduled for April 2015 (under the SGR formula) will be overridden in legislation. This projection does not represent a policy recommendation by the trustees, nor a political prediction, still less a recommendation that such a cost-increasing override need not be offset with other savings. Two reasons for this change stand out.

One is that for years the trustees have warned that due to the historical pattern of overriding SGR payment reductions, actual costs are likely to be higher than under current schedules. This year, instead of emphasizing a projection likely to understate future costs, the trustees decided to emphasize a scenario that did not have this problem. The other reason for the change was to achieve greater consistency throughout the report. If we really expected the 21 percent physician payment reduction to occur, then we would also expect to see sudden access problems, corresponding reductions in the volume of healthcare services, lower Part B premiums, and a lower contingency reserve required for the SMI trust fund. Previous trustees' reports had projected none of these things. Implicitly, most of the report had always assumed continued SGR overrides; now our main cost projections are more consistent with that assumption.

Slower Health Expenditure Growth Is Not Eliminating the Problem

This year the trustees somewhat lowered our healthcare cost growth projections in response to updated data, lowering our estimate of the 75-year imbalance in HI from 1.11 percent of taxable payroll to 0.87 percent. Per the message I co-authored with my fellow public trustee Robert Reischauer, "questions arose as to whether a recent slowdown in national health expenditure growth may indicate less urgency in legislating Medicare financing corrections. Unfortunately, this is not the case. The Trustees' projections have long assumed that over the long term NHE growth will slow relative to historical trends... even with the assumption of decelerating spending growth Medicare's financing shortfall, like Social Security's, remains a reality warranting legislative corrections."

No Funding Warning This Year

By law the trustees are required to determine whether projected general revenue funding will exceed 45 percent of total Medicare outlays within the next 7 fiscal years. "Two consecutive such determinations trigger a Medicare funding warning." This test was established to "call attention to Medicare's impact on the Federal budget." In large part because of the recent Medicare spending slowdown, there is no funding warning in this year's report.

In summary, the Medicare report continues to show that program finances are on an unsustainable long-term trajectory largely due to demographic change, placing rising pressure on the federal budget and requiring legislative corrections, despite favorable adjustments to recent and projected rates of Medicare spending growth.