- | Government Spending Government Spending

- | Expert Commentary Expert Commentary

- |

The One Budget Reform that Matters

Unless and until we address the mandatory spending framework that undercuts lawmakers’ ability to manage the federal budget, no other process reforms are likely to matter.

Proposals to reform the federal budget process are much in the air these days. While there is widespread belief that the process is broken, definitions of that breakage vary widely. Complaints include that the process is overly complex, cumbersome and outdated, that it promotes short-term thinking over long-range planning, lacks transparency and accountability, fails to uphold Congress’s constitutional powers, fails to advance national priorities, and promotes bad fiscal outcomes. Because budget reform proposals reflect such a wide range of motivations, they take a wide variety of forms. Yet if a central goal is to meaningfully improve federal financial management, only one reform is likely to matter: in the words of Gene Steuerle and Rudy Penner, restoring “more discretion to the federal budget.” More on that later.

Though many budget process reforms might be desirable for various reasons, this does not mean they will necessarily result in better budgeting. For example, it may be good government practice to publicly disclose the texts of budget resolutions and amendments before they are considered; there is no guarantee that doing so will result in more public pressure for fiscal responsibility, rather than more interest group pressure to relax fiscal constraints. Similarly, biennial budgeting may free lawmakers’ time to consider legislation more thoroughly. Whether this would result in more or less deficit spending remains to be seen.

Even well-considered legislation to improve Congress’s appropriations process may have minimal impact on federal finances. This is because appropriations – basically the spending Congress determines anew each year -- already represent a deteriorating percentage of total federal spending. Even if the appropriating process were perfected, we could still end up with uncontrolled federal spending and deficits due to the automatic growth of entitlements under existing law.

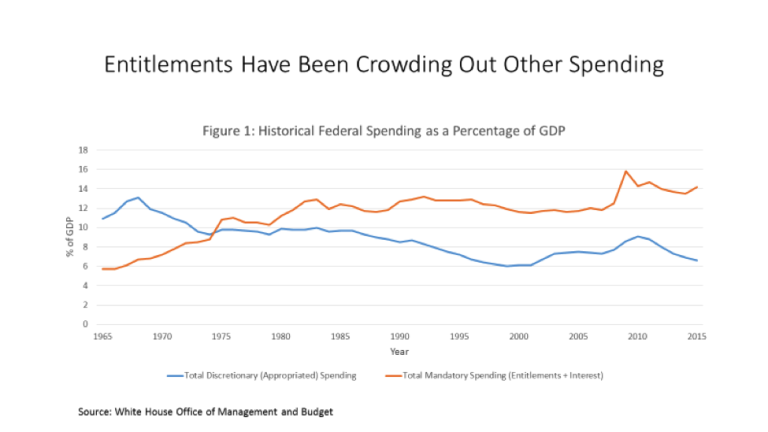

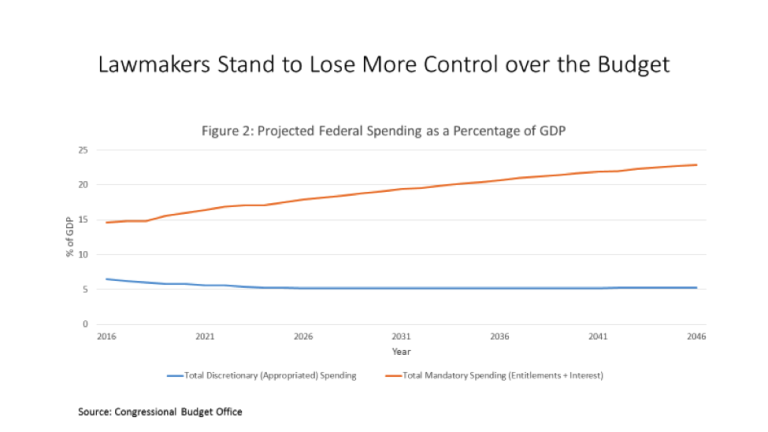

Entitlement programs are those automatically authorized to continue to spend funds, often in increasing amounts, without further legislative action. Some of the biggest examples include Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. Figure 1 shows how over time, automatic growth in such programs has precipitated a corresponding relative decline in discretionary/appropriated spending. (Interest costs are grouped with entitlements here because they are also mandatory spending; their inclusion does not affect the qualitative trend). Figure 2 shows that under current projections mandatory spending will continue to absorb an ever greater share of budget resources. In sum, unless and until the laws governing mandatory entitlement programs are changed, lawmakers will only exert annual control over a shrinking fraction of the budget.

Reasonable people can and do differ over what constitutes responsible fiscal policy. Because of these differences, budget reforms designed to advantage one side’s fiscal views will be resisted by the other. The current process, however, is an equal-opportunity offender: it does not readily allow any legislative coalition’s fiscal policy views to be implemented. This is because the vast majority of the budget does not reflect the decisions or even consent of current lawmakers; rather, it reflects decisions made many years ago by legislators holding information since rendered obsolete. Unless a new legislative coalition can be formed to change those laws, that problem automatically worsens.

Members of Congress on both sides of the aisle share a stake in fixing this. Believers in a more activist government, for example, would like to see consistently more spending on transportation infrastructure. But because of the automatic growth of entitlement spending this has not happened, and won’t without a process change. Believers in a more restrained government would like to reduce the drag of taxes on economic growth. Again because of automatic entitlement spending increases, this has not happened and will not without precipitating larger deficits. Under current practices neither side gets what it wants, nor do they get a compromise between what they respectively want.

Because of this dynamic, lawmakers would do well to shed a zero-sum view of fiscal policy, in which one side’s gain is perceived as the other’s loss. It might well have once been true that the mandatory spending system advantaged the perspectives of those on the political left. Now that such spending has grown to where it paralyzes progressives’ attempts to spend on their chosen priorities, that is no longer the case. Both sides lose under the current system, and both sides would gain by reforming it.

Previous lawmakers attempted to impose fiscal discipline on mandatory spending by establishing trust funds for such items as Social Security, Medicare and highway spending. The idea was that these programs would be forbidden to spend in excess of the revenues raised for their respective trust funds. Unfortunately, this attempt at fiscal discipline has largely failed. Many trust funds, such as those for Medicare Parts B and D, impose no constraints at all because the federal government’s general fund automatically gives them whatever money they lack to meet expenses. Lawmakers have also supplemented Social Security’s trust funds with hundreds of billions of general fund dollars. At this point, whether a program has a trust fund provides no meaningful information about whether it strains the general federal budget.

The recent Steuerle-Penner paper, “Options to Restore More Discretion to the Federal Budget,” offers several proposed reforms to address these challenges. These include, among others, automatic triggers to slow the growth of federal mandatory spending and tax-code entitlements, as well as requiring periodic congressional votes on whether to allow full scheduled increases in program spending. Of particular interest are their presentational recommendations. Steuerle-Penner would have Congress supplement the current confusing “budget baseline” methodology with other presentations disclosing the budget’s areas of real growth. Having the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) routinely release such reports could potentially further essential public and media awareness of the drivers of fiscal pressures.

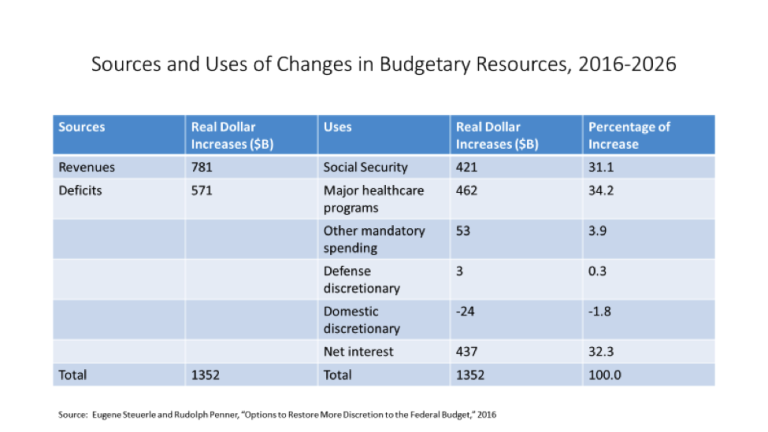

Steuerle-Penner show such a table containing the following data:

Steuerle-Penner summarize the table aptly as showing that over the next ten years, “almost one-third of the increase in budgetary resources will be devoted to Social Security, one-third to major healthcare programs, and one-third to interest on the debt. Close to nothing is left for everything else, including most programs for education, infrastructure, the environment, and energy. Social Security and healthcare entitlements may be good and popular programs, but should the federal government really be spending almost all new resources on them and on interest?”

Different people will have different answers to those questions. But at the very least, they should be discussed and deliberately decided. Our failure to address such questions has resulted in a budget process that has spiraled ever more wildly out of control. Unless and until we address the mandatory spending framework that undercuts lawmakers’ ability to manage the federal budget, no other process reforms are likely to matter.