I’m Ben Klutsey, program manager for the Financial Markets Working Group and the Program on Monetary Policy at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

We recently hosted a conference in Starkville, Mississippi, to mark the 100th anniversary of the Uniform Small Loan Law of 1916. I served as a moderator of one of the panel discussions during our conference.

After discussing the history of consumer credit in the United States, the current state of regulatory affairs surrounding consumer credit, and the future of consumer credit products with all of the participants, I began to wonder how this information might apply to someone in the real world. What if someone needed a loan for an emergency repair? What alternatives would such a person consider?

Please join me in exploring our hypothetical consumer, Violet, and her options to repair her broken sink with the information discussed at the conference.

At a time when the future of the small-dollar loan regulatory landscape is changing around the country (consider, for example, the recently finalized small-dollar rule by the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection), people are sometimes left with fewer borrowing options to cover a large unexpected expense, such as emergency home or car repairs or medical bills.

Now let’s consider the plight of our hypothetical consumer, Violet. She has a problem. Her sink is hopelessly clogged.

Violet calls in AV Plumbers, which gets the sink unclogged and addresses the water damage, but presents her with a $700 bill — the hefty price includes a surcharge for after-hours, emergency service. Violet doesn’t have the money on hand to pay the bill, and most of her next two pay checks are already earmarked to pay for her mortgage, utilities, and food.

Violet doesn’t have a rainy-day fund or a gaggle of rich relatives willing to lend her money. She would be ashamed to borrow money from friends, so she needs to borrow money from a third party.

So where does she go to borrow the money? Regulations play a big role in defining Violet’s options.

Problems like Violet’s aren’t new. And neither is the government’s interest in setting the parameters for how and from whom consumers can borrow.

Professor Lendol Calder of Augustana College, author of Financing the American Dream, explains that debt came to America on the Mayflower and never left.

Now, back to Violet.

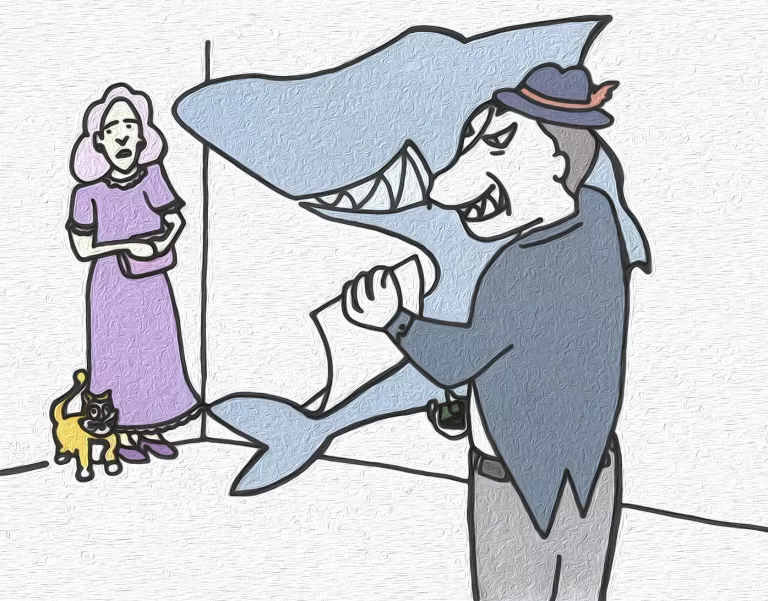

Violet could go to a “loan shark,” a lender who operates outside of any legal framework and thus may charge high interest rates and use creative enforcement methods to cover his legal risk. As former Federal Reserve economist and consumer credit expert Dr. Thomas Durkin explains, if Violet had lived in the early 20th century, visiting an unsavory loan shark might have been her only option. Legal lenders could not afford to lend on the terms permitted by state law, so illegal lenders picked up the slack.

The quandary of consumers led a group of philanthropists and would-be lenders to design a regulatory framework that would foster legal, safe consumer loans. The result, as Thomas Durkin explains, was the model Uniform Small Loan Law of 1916. Professor Tom Miller, holder of the Jack R. Lee Chair in Financial Institutions and Consumer Finance at Mississippi State University, put the USLL initiative into context as part of the broader progressive movement in the early 20th century. The USLL initiative became the model on which many states built their laws governing the provision of small-dollar loans. Within a few years, Professor Calder tells us, the USLL-inspired laws “covered about 75% of American borrowers and probably even more importantly [the USLL] brought into being a new kind of small loan lender who had not existed before.”

Back to Violet, who is sitting down to think through her options. Although we often assume that consumers make irrational money decisions, especially in emergencies, Dr. Gregory Elliehausen, a Federal Reserve expert on the economics of consumer finance, explains that consumers “using limited information, not considering all choices, or doing an extensive analysis can nevertheless make utility-increasing decisions.” Likewise, Todd Zywicki, a professor of law at the Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University, notes that the efforts to show “that consumers systematically make mistakes and therefore are systematically exploited by financial institutions” have not been successful.

Regulations require lenders to provide Violet information about rates and terms so she can compare her loan options. Mark Calabria, formerly of the Cato Institute and now chief economist for Vice President Pence, notes that disclosure regulations could be a response to asymmetric information — one of a number of market failures that economists look for before recommending regulation.

Violet could take her great-grandmother’s diamond wedding band to B&B pawn shop, but the sentimental value of the ring is high. Violet feels less emotional attachment to her car, so she could use its title as collateral to get a loan. But Violet needs her car in order to get to work, so doesn’t want to risk losing it. What about a payday loan? A recent change in the laws of her state caused all the local payday lending stores to close. Hilary Miller, president of the Consumer Credit Research Foundation, explains that regulations that drive competitors out can actually harm consumers.

Since Violet can’t get a payday loan, she thinks of other options.

Why doesn’t Violet just go down to her bank and get a small loan? Consumer credit expert Alex Horowitz of the Pew Charitable Trusts explains that banks and credit unions want to make small-dollar consumer loans, but they can’t do so until they get some clarity from their regulators. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency recently took a step in that direction by rescinding its Deposit Advance Products Guidance.

Making regulatory changes that would facilitate small-dollar lending by banks and credit unions would help consumers like Violet. Dr. Janis Pappalardo, assistant director of the Consumer Protection Division of the Federal Trade Commission, explains that there is a place for regulation of small credit, but “it’s really important, if you want to improve consumer welfare and social welfare, to promote competitive markets, and that strong competition really helps consumers.”

Dr. Pappalardo goes on to explain that sometimes it may even make sense to ban a particular consumer credit product, but regulators need to be careful in doing so because consumers are not all the same. A loan product that might not work well for Violet’s friend Scarlett could be suitable for Violet.

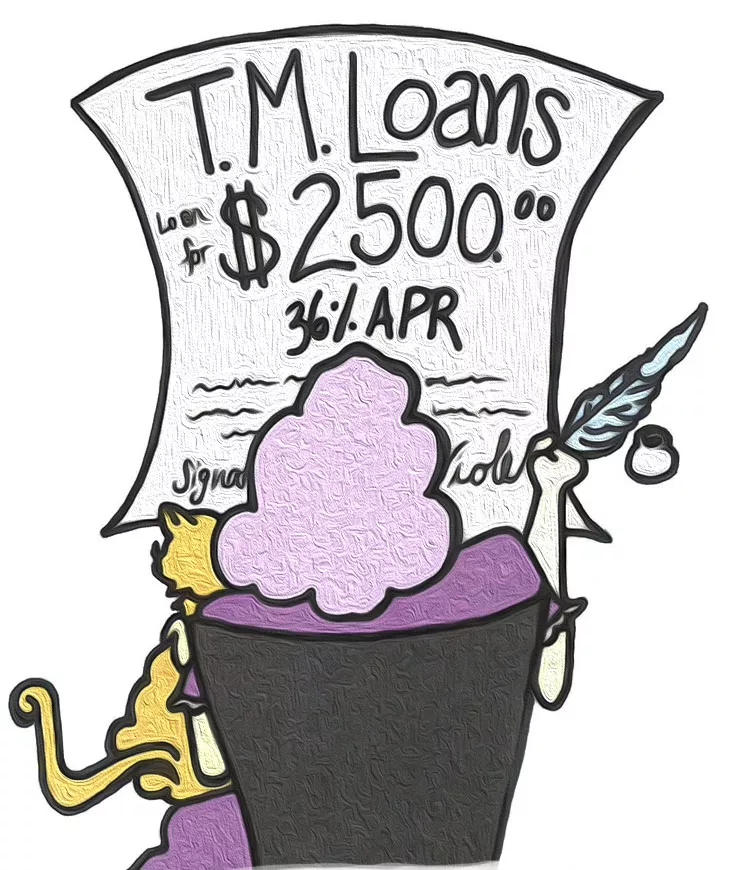

Violet finally decides to go down the street to talk to the local installment lender, TM Loans. As Bill Himpler from the American Financial Services Association explains, she can repay such a loan in equal installments over a fixed term. Traditional installment loans grew directly out of state laws based on the USLL. Well before that, people were paying for consumer durable goods in installments. Martha Olney, teaching professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, has traced Americans’ use of manufacturer-provided installment credit to buying sewing machines, pianos, furniture, and automobiles.

States have long been the frontline regulators of consumer credit because — as Commissioner Charlotte Corley from the Mississippi Department of Banking and Consumer Finance illustrates — they are familiar with consumers like Violet.

However, federal regulators have shown an increasing interest in the area, which has raised concerns by state officials like Mississippi Lieutenant Governor Tate Reeves, who points out that federal regulators like the CFPB may not have the appreciation that state policymakers have for the needs of the consumers in their states. A well-paid regulator in Washington might not understand how important a wide variety of credit options is to a consumer of limited means like Violet.

State regulators don’t always understand the value of options, either. If Violet lived in the middle of Arkansas, she would not be able to get a traditional installment loan. Arkansas, unlike the other states, did not model its laws after the USLL. State interest rate caps are so low that it is unprofitable for lenders to make these types of loans. Professor Tom Miller explains that these laws have made the interior of Arkansas a loan desert. Residents of outer counties can cross the border to borrow, but interior residents cannot afford the time and expense of driving to another state.

Violet, however, is not a resident of Arkansas, so she enters TM Loans and sits down with an employee, who asks her lots of questions about her income, assets, and how she plans to use the loan. Traditional installment lenders underwrite their loans and turn down borrowers they do not believe will repay them. So, Violet decides to borrow $2,500 at a 36 percent annual percentage rate (APR).

Thirty-six percent may sound alarming to people who are more familiar with loan products like mortgages and car loans. State regulators have historically imposed rate caps as a way of protecting consumers. Violet’s state has a 36 percent cap, which is a common cap in many states, but such a cap may actually harm Violet. The 36 percent cap precludes Violet from borrowing just the $700 she needs, rather than the installment lender’s $2,500 minimum. Tom Durkin explains that a 36 percent APR is not enough for lenders to make a profit on small loans, so many lenders simply don’t make loans below a certain dollar amount because they won’t break even.

However, as Mark Calabria notes, profits cannot be regulated away without affecting access to products and services. A properly functioning market generates a price that is low enough for Violet to take out the loan and high enough for the lender to make the loan.

In any case, a competitive consumer credit market ensures that Violet can pay the plumber. She, like other consumer credit borrowers, has decided that getting money when she needs it justifies taking out a loan she will have to pay back over time. Professor Calder believes that even the repayment responsibility can be a positive in a consumer’s life.

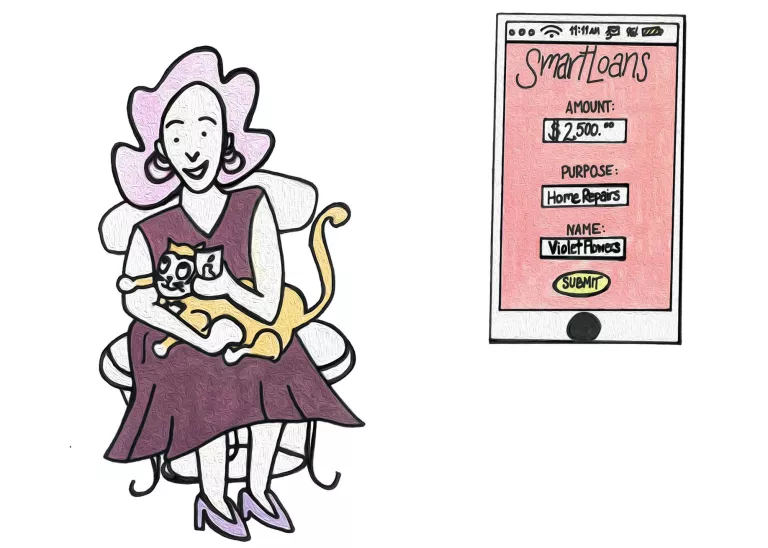

A future Violet might have even more options, which will make it easier and cheaper for her to borrow.

J. Alton Hosch Associate Professor at the University of Georgia School of Law Mehrsa Baradaran, author of How the Other Half Banks, argues that post offices could be the wave of the future to meet the saving and borrowing needs of consumers like Violet. Others, like Mercatus Center Senior Research Fellow Brian Knight, are looking at the potential for technology to increase access to consumer credit. For that potential to materialize, certain regulatory barriers might need to be addressed. So, Brian has some suggestions about how regulators should think about these issues.

One thing is certain: regulation will be just as important in defining the range of credit options available to future Violets as it has been for the Violets of the past. Present Violet weighed her loan options, which are defined by today’s regulatory framework, and found the best option to pay for the repair of her clogged sink.