- | Government Spending Government Spending

- | Data Visualizations Data Visualizations

- |

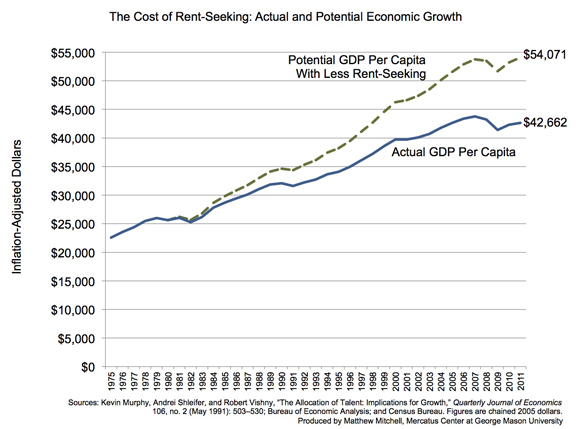

The Cost of Rent-Seeking: Actual and Potential Economic Growth

One of the things holding productivity back and, along with it, compensation, is rent-seeking. When governments dispense privileges to particular firms, entrepreneurs spend their time asking politicians for those privileges instead of devising new ways to create value for customers. Economists call this activity rent-seeking, and research suggests that it depresses productivity growth.

Economists observe that people are generally compensated based on the value they produce. In other words, when people are more productive, they tend to earn more. These trends can be seen in the historical record. Over time, people have gotten more productive, and that has translated into income gains for the average worker.

In recent years, however, the gains have been meager for all too many. One of the things holding productivity back and, along with it, compensation, is rent-seeking. When governments dispense privileges to particular firms, entrepreneurs spend their time asking politicians for those privileges instead of devising new ways to create value for customers. Economists call this activity rent-seeking, and research suggests that it depresses productivity growth.

Economists Kevin Murphy, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert Vishny studied this phenomenon using data from dozens of countries. They found that a 10 percentage point increase in the share of students concentrating in law was associated with 0.78 percentage point slower annual growth in per capita GDP. In other words, economic growth was slower in countries where there seemed to be more rent-seeking.

In this week’s chart, Mercatus senior research fellow Matthew Mitchell shows how this difference compounds over time. If, since 1980, per capita GDP had grown 0.78 percentage points faster than it actually did, then 2011 per capita production would have been $54,000 rather than $43,000. “When governments dispense privileges,” Mitchell says, “economic growth is diminished. This isn’t just an abstract idea. It means that real people earn less money than they otherwise could.”

In Mitchell’s new paper, The Pathology of Privilege, he writes:

“Up to a certain point, lawyers are theoretically good for growth; they help delineate and define property rights and they help maintain the rule of law. But beyond some minimum point, more lawyers may lead to more rent-seeking. Even if lawyers themselves are not the cause of rent seeking, they may be an indication of it. In the same way that a large number of police per capita may be an indication of a city’s inherent violence, a large number of lawyers per capita may be an indication of a nation’s tendency to rent-seek.”

Matthew Mitchell is a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. He blogs about economics and economic policy at NeighborhoodEffects.com.