- | Academic & Student Programs Academic & Student Programs

- | Regulation Regulation

- | Policy Briefs Policy Briefs

- |

The Costs and Consequences of Unemployment Benefits on the States

Unemployment insurance programs in the states have been approaching insolvency for more than a decade, putting pressure on states to raise payroll taxes, cut benefits, or seek federal loans. None of

The duration and depth of the current recession reveals the risks associated with the federal-state unemployment insurance programs. Unemployment insurance programs in the states have been approaching insolvency for more than a decade, putting pressure on states to raise payroll taxes, cut benefits, or seek federal loans. None of these options are desirable during a recession, when individuals need the benefits most and states can least afford to increase taxes. The best solution to providing unemployed workers with income security is to give workers autonomy over savings dedicated to covering unemployment.

UNEMPLOYMENT BENEFITS

Unemployment Insurance is a joint federal/state program created by the Social Security Act of 1935. Unemployment insurance programs are operated by the states under federal guidelines. States set eligibility requirements, coverage limits, and financing methods. A federal/state-levied payroll tax1 on employers based on the total taxable wages paid to workers funds the program.2 Though the tax is levied on employers, it is passed on to employees in the form of decreased wages.3

The federal/state program extends benefits for up to 26 weeks to full-time workers who lose their jobs. During periods of low unemployment, payments into the fund are high relative to benefits paid out, and the trust fund grows. During periods of high unemployment, payments into the fund fall, payouts increase, and the trust fund is depleted.

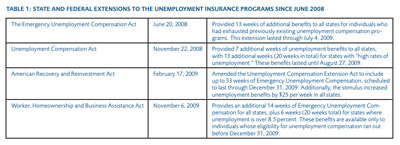

When states exhaust their unemployment trust funds, states may borrow to continue paying benefits. The federal government may also offer aid to workers in states with high unemployment through Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC). The federal government has extended EUC four times since February 2009, amounting to an additional 86 weeks of unemployment insurance for states (see Table 1).

CONSEQUENCES OF UNEMPLOYMENT BENEFITS ON WORKERS

In a troubled economy, unemployment benefits provide individuals with some income security as they look for work. However, unemployment benefits also change the incentives facing the unemployed, lengthening the job search. By easing the pressure of finding employment, the system benefits the unemployed at the expense of overall productivity and long-run economic growth. Social welfare programs may also change workers' mentalities, leading workers to become less driven and unhappier as their dependence on the state increases.4 Optimal design of unemployment insurance must consider how the payoff and duration of benefits relative to the worker's previous income affect the individual's incentive to seek employment.

The perverse incentives of unemployment benefits are well documented.5 Subsidizing unemployment draws out a job search. Generous benefits that subsidize "temporary idleness" may result in "chronic idleness."6 As the state makes chronic idleness more attractive, more and more people will choose that option over productive employment. As people remain unemployed, their decreased spending will slow production throughout the economy, and the system will become less and less sustainable.

In addition to these relatively short-run dangers, unemployment benefits can create a more serious long-run consequence known as hysteresis, or systemic long-run unemployment. As workers remain out of the job market for longer periods, their skills become obsolete and the likelihood of remaining unemployed increases.7 As unemployment becomes acceptable, the natural rate of employment and production falls, resulting in a less-skilled workforce.

Identifying hysteresis is difficult. However, it is possible to measure the effects of changes in unemployment benefits on workers. Economists Lawrence F. Katz and Bruce D. Meyer observe that workers receiving unemployment benefits were likely to find a job right before their benefits expired.8 Analyzing EU data, Katz and Meyer find that extending benefits from six months to a year would likely increase periods of unemployment by approximately one month.9 Their findings suggest that while unemployment benefits are often extended to help workers, they have the effect of damaging economic development and productivity.

THE IMPACT OF UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE ON EMPLOYERS AND STATE FISCAL POLICY

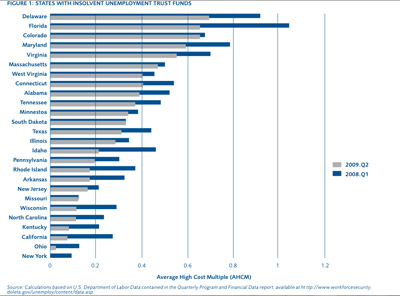

Federal guidelines suggests states maintain, at minimum, unemployment trust fund reserves for one year's projected payment needs, based on the highest level of benefit payments experienced in the state over the last 20 years. To determine the solvency of unemployment trust funds, states use the Average High Cost Multiple (AHCM). The AHCM is the ratio of the unobligated balance in the unemployment trust fund to the average of the three highest years of unemployment benefits paid out. States that enter a recession below an AHCM ratio of 1.0 are at risk of insolvency. As of October 2009, unemployment insurance funds of 33 states were at a solvency ratio of less than 1.0 and 21 of those had solvency ratios below 0.5 (see Figure 1).

In the next two years, 40 state unemployment insurance funds may be completely depleted. The states will need $90 billion in federal loans to keep paying benefits.10 To date, 25 states have depleted their funds and are relying on $24 billion in federal loans to function.11 To replenish unemployment trust funds, states with low solvency rates will need either to reduce or eliminate benefits or increase payroll taxes in 2011. The tax increase will likely exacerbate unemployment by making it more expensive for firms to hire new employees. These states hold those loans interest-free through December 2010,12 but will be required to begin paying interest in 2011, creating future obligations.

POLICY RECOMMENDATION: UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE SAVINGS ACCOUNTS

Unemployment insurance is meant to support workers who lose their jobs during downturns. However, public unemployment insurance produces unintended consequences,leading to lower prosperity. A more effective approach to providing support for workers is to establish Unemployment Insurance Savings Accounts (UISA).13 These individual savings accounts are funded by a percentage of wages contributed by the employee and employer in lieu of the compulsory contributions currently made by employers to public trust funds. When an individual becomes unemployed, she may access the account. If the individual is never unemployed, she can roll those savings into a retirement account.

UISA eliminates the perverse incentives of publicly provided benefits. Workers must finance their own unemployment, providing an incentive to avoid job loss and increase the job search effort during unemployment. Reducing the payroll tax on employers would increase wages, leading to higher contributions to UISA accounts. While the current program is a tax on all of the employed (some of whom will never use the benefit), a UISA belongs to an individual worker. Essentially, UISA is a form of forced savings: A worker's contribution to the unemployment account is paid directly back to her.14 Chile adopted this approach in 2003, and empirical data suggests that most Chilean workers are better off as a result.15 Employees contribute 0.6 percent of monthly earnings, and employers contribute a further 2.4 percent to an individual savings account. An unemployed worker may draw between 30 to 50 percent of the previous wage for up to five months.16 Upon retirement, unused unemployment savings roll into the worker's personal savings account.17

CONCLUSION

The current recession reveals the inadequacy of the Unemployment Insurance program. In addition to the negative incentives public unemployment benefits create for productivity, job search, and individual saving, unemployment benefits create an economic hazard for states that must replenish trust funds during economic downturns via increased payroll taxes on businesses—which in turn discourages hiring. A better way to provide income security for workers is to establish private Unemployment Insurance Savings Accounts, whereby workers and their employers contribute to the workers' savings accounts, which they can draw upon during periods of unemployment. By financing their own unemployment funds, workers have an increased incentive to avoid job loss and increase job search efforts. Reducing the payroll tax on employers would increase wages and encourage hiring. The individual employee contribution not only promotes individual saving, but also provides greater certainty and fairness, ensuring that all workers receive their portion of the tax currently levied to provide public unemployment benefits.

ENDNOTES

1. The Federal Unemployment Tax is 6.2 percent of taxable wages. Employers who pay the tax on time receive a credit of 5.4 percent, regardless of the tax rate they pay to the state. This means that, in general, the effective federal payroll tax rate is 0.8 percent. See U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration Web site, http://www.ows.doleta.gov/unemploy/uitaxtopic.asp. State payroll tax rates vary. Minimum tax rates range from 0 percent to 1.69 percent, and maximum rates range from 5.4 percent to 10.96 percent. See Kathleen Romig and Julie M. Whittaker, "The Unemployment Trust Fund (UTF): State Insolvency and Federal Loans to States," Congressional Research Service, January 21, 2009.

2. Not all of an earner's wages are taxable. There is a ceiling amount beyond which there is no additional tax liability. The current federal ceiling is $7,000 and states may set a ceiling beyond this amount.

3. Overview of Present Law and Economic Analysis Relating to Marginal Tax Rates and the President's Individual Income Tax Rate Proposals, The Joint Committee on Taxation, March 6, 2009, http://www.jct.gov/x-6-01.pdf.

4. For more on the negative psychological and economic impacts of the welfare state, see James Bartholomew, The Welfare State We're In (London: Metheun, 2004).

5. See, for example, Tax Foundation Incorporated, "Unemployment Insurance: Trends and Issues" Research Publication no. 35, http://www.taxfoundation.org/news/show/2022.html; Francesca Valentini, "Unemployment Insurance Savings Accounts: An Overview," ETLA Discussion Paper no. 1136, http://www.etla.fi/files/1994_Dp1136.pdf; and William B. Conerly, "Unemployment Insurance in a Free Society," NCPA Policy Report no. 274, March 2005, http://www.ncpa.org/pdfs/st274.pdf.

6. Economist W.H. Hutt has explored the negative impact that "generous" unemployment benefits have on economic growth. Steve Horwitz explains Hutt's view: "Unlike preferred idleness, where a worker chooses to forgo a contractual wage in order to consume leisure, chronic idleness occurs when idleness is subsidized by various income transfers. Hutt argues that such subsidies prevent the temporary idleness created by wage barriers from being eliminated through sub-optimal employment and turn it into chronic idleness." See Steve Horwitz, Microfoundations and Macroeconomics: An Austrian Perspective (London: Routledge, 2000), 193.

7. For more on this problem, see Olivier J. Blanchard and Lawrence H. Summers, "Hysteresis and the European Unemployment Problem," NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1986, Volume 1 (1986), Stanley Fischer, ed.

8. Lawrence F. Katz and Bruce D. Meyer, "The Impact of the Potential Duration of Unemployment Benefits on the Duration of Unemployment," NBER Working Paper no. 2741, October 1988.

9. Ibid.

10. Peter Whoriskey, "State's jobless funds are being drained in recession," The Washington Post, December 22, 2009, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/12/21/AR20091….

11. Ibid.

12. U.S. Department of Labor, "UI Budget," http://www.ows.doleta.gov/unemploy/budget.asp.

13. Cascade Policy Institute, "The Individual Asset Account (IAA): Turning Unemployment Insurance (UI) into an Asset," http://www.cascadepolicy.org/unemployment-insurance/.

14. Francesca Valentini, "Unemployment Insurance Savings Accounts: An Overview," The Research Institute of the Finnish Economy Discussion Paper no. 1136, May 9, 2008, 11, http://ideas.repec.org/p/rif/dpaper/1136.html.

15. Ibid.

16. International Social Security Association, "Unemployment Insurance in Chile: Reform and Innovation," July 14, 2009, http://www.issa.int/aiss/News-Events/News2/Unemployment-insurance-in-Ch…. For individuals who do not have enough funds accrued in their account, the Chilean system also establishes a common pool fund from which unemployed individuals may draw payments for up to five months. See Francesa Valentini, "Unemployment Insurance Savings Accounts: An Overview."

17. In January 2009, Chile reformed the program to address aspects of unemployment in labor markets. The reforms extend participation to workers in higher turnover markets and expand the period during which workers can draw upon funds.

To speak with a scholar or learn more on this topic, visit our contact page.