- | Government Spending Government Spending

- | Data Visualizations Data Visualizations

- |

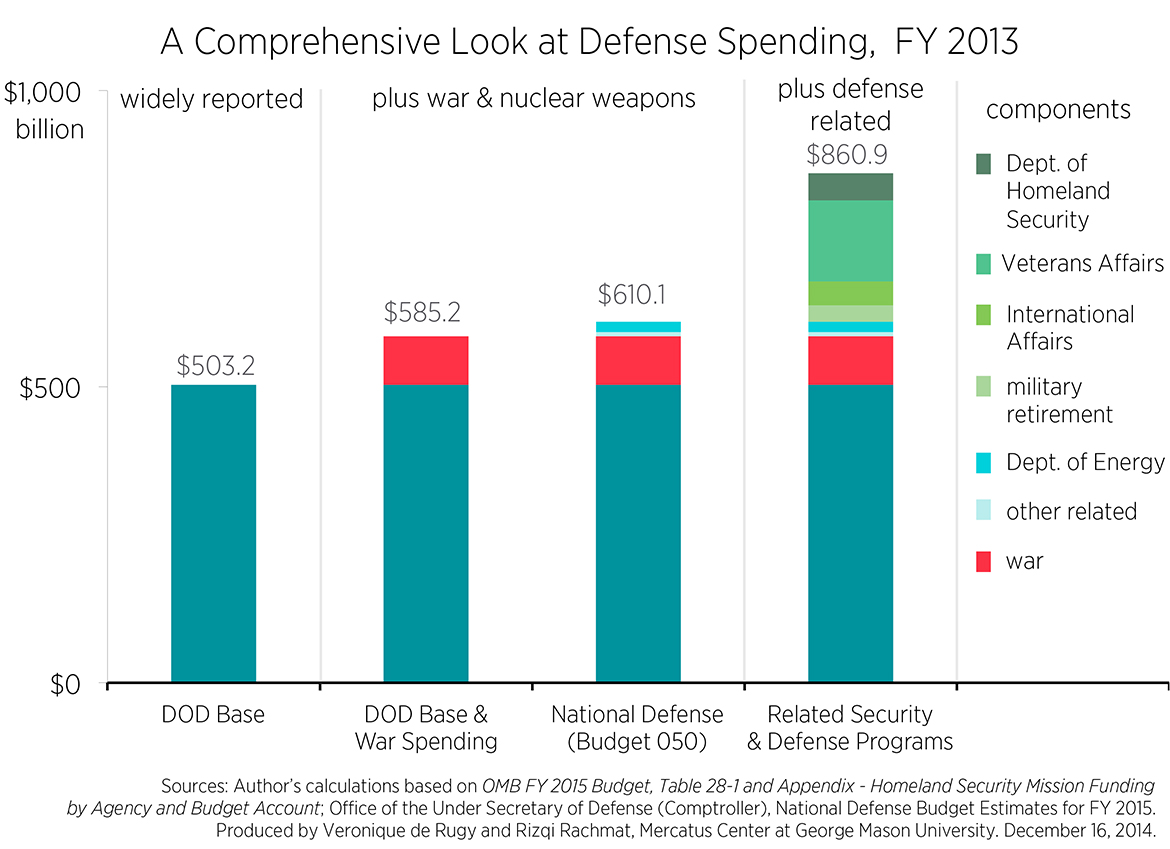

Defense Funding Extends Beyond the Pentagon’s Budget

This week’s chart puts into perspective the amount of funding—and expense—that is not accounted for in the figures widely cited by policymakers and defense officials.

Policymakers and defense officials have recently expressed concern that defense spending is insufficient, citing the recent drop in base defense funding as proof. The use of this lower figure understates the actual taxpayer cost of maintaining the United States’ global military presence and interventionist foreign policies.

This week’s chart puts into perspective the amount of funding—and expense—that is not accounted for in the figures widely cited by policymakers and defense officials.

Using a methodology conceived by Winslow Wheeler of the Project on Government Oversight, line items from other areas of the federal budget relevant to defense and security issues are added to the fiscal year 2013 base. Once these expenses are included, it’s clear that the reported defense spending figures underestimate the overall cost of defense and national security programs by over $350 billion in fiscal year 2013 (the most recent year of finalized data).

The Pentagon’s base budget is the most widely reported defense funding estimate and was $503 billion in fiscal year 2013. This $503 billion figure excludes an additional $82 billion in war funding, which increases the total to about $585 billion. The defense base budget also doesn’t account for the nuclear weapons programs contained in the Department of Energy’s budget or other related defense spending, which would add another $25 billion to defense spending, pushing the total to $610 billion. This is 20 percent higher than the widely cited base figure—that is, at least one dollar in five in defense funding is not part of the Pentagon’s base budget.

While the majority of defense spending takes place in either the Pentagon budget or National Defense budget function, there is other funding related to national security and defense:

- • $137 billion to Department of Veterans Affairs to care for wounded or retired military veterans.

- • $46 billion to Department of Homeland Security for responding to terrorism and natural disasters.

- • $41 billion to International Affairs for additional war funding, weapons training to foreign militaries, and foreign aid. There are nondefense-related items in this amount, such as operating US embassies and consulates and normal diplomatic operations. However, these are all key components of the US government’s national security apparatus.

- • $27 billion for retirement costs for military pension benefits not included in the Pentagon’s budget.

When all these categories of funding are included, the more comprehensive defense funding figure comes out to $861 billion. It’s important to note that this amount does not include the associated interest costs on the debt, which would add to the total amount.

When Republicans take control of both houses of Congress in the new year, defense funding is likely to come to come to the forefront of policy discussions. Many in the party have been arguing that budget caps implemented by the 2011 Budget Control Act have been too restrictive on defense spending, pointing to the Pentagon’s base budget, which has receded from its peak in fiscal year 2010. What often goes unacknowledged is the fact that war funding is not subject to the caps. Moreover, the associated cost categories discussed above are routinely ignored. If the nation is to have an honest discussion and debate on the appropriate amount of funding for national defense, policymakers should acknowledge that the Pentagon’s allocation is just the tip of the iceberg.