The midnight regulation phenomenon is not new or limited to one political party. New research suggests that midnight regulations proposed during the second half of a presidential election year are more likely to have lower-quality regulatory analysis and less likely to use the results of analysis to inform decisions. Thus, these regulations may be particularly costly or ineffective.

The federal government usually experiences a surge of regulatory activity during the last quarter of a presidential election year. The surge is especially large when control of the presidency switches parties.[1] Scholars call this phenomenon “midnight regulation.”[2]

New research from Mercatus Center scholars reveals that rushed midnight regulations proposed during the second half of a presidential election year have lower-quality regulatory analysis, and agencies are less likely to use the analysis to make decisions about the regulation.[3] These regulations are more likely to be ineffective or excessively costly.

WHAT IS REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS?

For more than three decades, presidential executive orders have required federal agencies to conduct regulatory impact analyses (RIAs) to identify the problem a new regulation tries to address, assess its significance, examine a wide range of solutions, and assess the costs and benefits of alternative solutions. Agencies should regulate only when the benefits justify the costs.[4]

The Mercatus Center’s Regulatory Report Card assesses the quality and use of RIAs for “economically significant” proposed regulations. Economically significant regulations have costs or benefits exceeding $100 million annually or various other important adverse effects.[5] They have the largest impacts as well as the most extensive analytical requirements.

RUSHED MIDNIGHT REGULATIONS HAVE LOWER-QUALITY ANALYSIS

The Bush administration attempted to curtail midnight regulations; a May 2008 memo from the chief of staff instructed agencies to propose regulations before June 1 and finalize them by November 1.[6] Nevertheless, agencies proposed 17 economically significant regulations after June 1, and eight of these were finalized between election day and inauguration day.

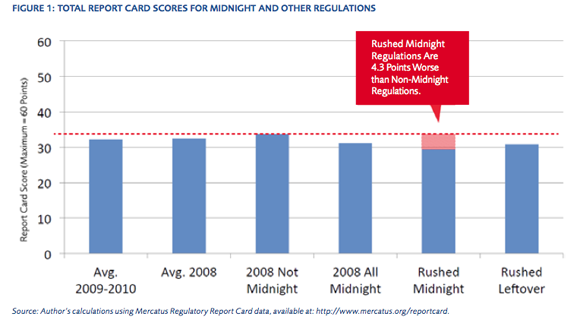

The Report Card evaluated the quality and use of analysis for the Bush administration’s midnight regulations adopted in 2008. The midnight regulations proposed after June 1 have lower quality and use of analysis than other regulations proposed in 2008, 2009, and 2010 (the three years for which the Report Card has evaluated all prescriptive regulations).[7] “Prescriptive” regulations impose mandates or prohibitions; excluded are budget regulations that implement federal spending or revenue collection programs. Figure 1 compares total Report Card scores for midnight regulations and other groups of regulations. Key results include the following:

- Prescriptive regulations scored an average of about 32 out of a possible 60 points in 2008–2010, equivalent to a grade of “F.”

- Rushed midnight regulations—that is, midnight regulations proposed after the Bush administration’s self-imposed June 1 deadline and finalized between election day and inauguration day—have much lower scores. The average difference is “statistically significant”— that is, the difference in scores likely reflects a real difference between the two types of regulations rather than just random variation.

- Some regulations proposed after June 1 were not finalized by the Bush administration but instead left for the Obama administration to finalize. These “leftover” regulations also had lower scores, and the average difference is statistically significant. Either these regulations were supposed to be midnight regulations but the clock ran out before they could be finalized, or less effort went into their analysis because they would be left for the next administration to finish.

- Midnight regulations have lower average scores than the Bush administration’s non-midnight regulations or regulations proposed by the Obama administration in 2009 and 2010. However, the regulations proposed before June 1 and finalized during the midnight period score about the same as other regulations proposed in 2008. Thus, the rushed nature of midnight regulations that were not proposed until the second half of the year appears to explain their lower scores.

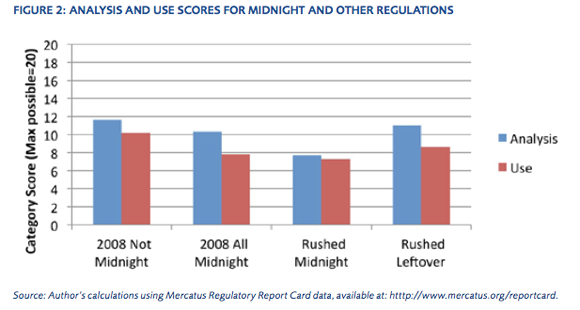

The Report Card divides score criteria into three categories: openness, analysis, and use. On openness, midnight and rushed midnight regulations had about the same scores as other regulations. Figure 2 shows, though, that midnight regulations have lower-quality analysis and less use of analysis than other regulations. As with the total scores in figure 1, the lower analysis score for all midnight regulations occurs primarily because the rushed midnight regulations have lower analysis scores.

However, the non-rushed midnight regulations also score lower than ordinary regulations on use. Thus, average use scores are lower for both types of midnight regulations. This means for midnight regulations, decision makers were less likely to explain how the analysis influenced their decisions or how they would evaluate the regulation’s performance in the future. Rushed leftover regulations have about the same analysis scores but lower use scores.

WHY POOR ANALYSIS?

Midnight regulations are a problem in part because they might not be thought through as carefully as other regulations. There are several reasons for this. The administration may have made a political decision to adopt these regulations regardless of what the analysis might show. Hence, agencies do not bother to perform high-quality analysis.

The surge of midnight regulations might overwhelm the ability of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) to conduct careful oversight, so more low-quality analysis survives the OIRA review process.[8] For rushed midnight regulations or rushed leftovers, the compressed time frame may make it impossible for agencies to conduct high-quality analysis even if they want to.

POLITICS VERSUS ANALYSIS

The results described above emerged after a statistical analysis that controlled for other factors that might have affected the quality or use of analysis. These factors include the type of regulation, the administration proposing the regulation, and whether the OIRA administrator was a presidential appointee or an acting administrator serving until Cass Sunstein was confirmed in September 2009.

Except for midnight regulations and midnight leftovers, there is little statistical difference between the average quality and use of analysis in the Obama administration and the Bush administration. In addition, the transition period before Sun- stein’s confirmation as OIRA administrator had neither better nor worse analysis than other periods.

However, regulations are susceptible to political influence, regardless of administration. Agencies identified by an expert survey as more “conservative” by virtue of their missions or cultures (e.g., Defense or Homeland Security) have higher- quality analysis than other agencies in the Obama adminis- tration. Agencies with more “liberal” missions or cultures (e.g., Labor or Health and Human Services) had higher-quality analysis than other agencies in the Bush administration.[9] Administrations of both parties seem to require less thorough analysis from agencies whose missions or cultures are more consistent with the administration’s ideology or priorities.

RESTRAINING RULEMAKING IN THE DARK

If history repeats itself, regulations proposed in the second half of 2012 are the ones most likely to be rushed and therefore to have lower-quality analysis and less use of analysis. Several types of reforms could mitigate an administration’s tendency to push through regulations at the last minute based on shoddy analysis:

- Self-imposed restraints: The Bush administration attempted to restrain midnight regulations by imposing deadlines. The evidence suggests that the deadlines reduced regulation during the midnight period and shifted some regulatory activity to earlier in 2008. This shift may have improved the quality of analysis by pre- venting agencies from rushing as many regulations, but it did not prevent all rushed regulations with lower-quality analysis from getting proposed or finalized.[10] Thus, self-imposed restraints may help but are not a complete solution.

- Limited regulatory volume: Limit the volume of rulemaking permitted during the midnight period.[11] A limit would allow agencies and OIRA to focus on conducting high-quality analysis and reviewing a limited number of regulations.

- Judicial review of RIAs: This reform addresses broader issues than midnight regulation, but it would have a salutary effect on the quality of midnight regulations because each agency would know that its analysis, or at least its explanation of how the analysis informed its decisions, would be subject to review by another branch of government.

CONCLUSION

The midnight regulation phenomenon is not new or limited to one political party. New research suggests that midnight regulations proposed during the second half of a presidential election year are more likely to have lower-quality regulatory analysis and less likely to use the results of analysis to inform decisions. Thus, these regulations may be particularly costly or ineffective. An administration might mitigate midnight regulations somewhat through self-imposed restraints. More effective solutions, however, would involve broader regulatory process reforms that either limit the volume of midnight regulations or impose external checks that prompt agencies to conduct high-quality regulatory analysis and use it to inform their decisions.

Learn more about Midnight Regulations