- | Government Spending Government Spending

- | Data Visualizations Data Visualizations

- |

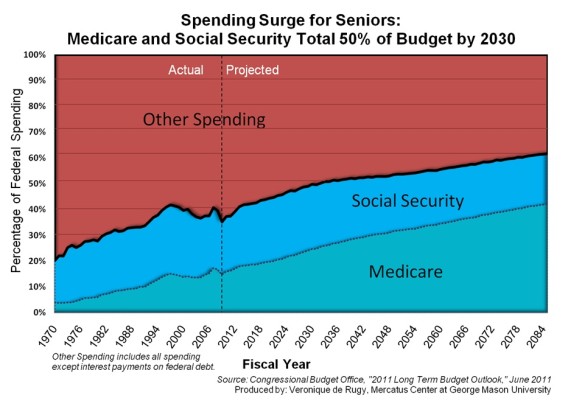

Spending Surge for Seniors: Medicare and Social Security Total 50 Percent of Budget by 2030

This chart examines the annual share of the U.S. budget spent on programs benefiting senior citizens.

This week, Mercatus Center Research Fellow Veronique de Rugy examines the annual share of the U.S. budget spent on programs benefiting senior citizens (i.e., those aged 65 and over). Data on Social Security and Medicare spending from the Congressional Budget Office is used to show the historical trends and projected share of the budget between 1970 and 2084.

This data underestimates the realities of federal spending for the old. According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in 2004, 28% of Medicaid spending went to those older than 65.

The growing number of beneficiaries due to the aging of the baby-boom generation will cause scheduled spending to surge. If current Social Security and Medicare policies continue without change, large deficits will undoubtedly emerge in the next decade and will grow even larger in subsequent decades.

Half of the entire budget will be consumed by payments for senior citizens by 2030.

In 1970, spending on Social Security and Medicare was one-fifth of the budget (blue portion). This portion has since grown to nearly 37 percent of the budget in 2010; this amounts to over twice spending on defense or 8.4 percent of the country’s gross domestic product. Other spending (red portion), which includes a variety of other mandatory programs (such as federal civilian and military retirement, veteran’s programs, and unemployment compensations) as well as discretionary programs, makes up a decreasing share of the budget in the future.

Combining Medicare and Social Security data alone underestimates the realities of federal spending for senior citizens. According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in 2004, 28% of Medicaid spending went to those older than 65. If we consider the portion of Medicaid for seniors, then roughly 40 percent of the 2010 budget was spent on the old; half of the budget will be spent on the old in the next decade.

These trends are not sustainable. For years, the federal government has used the tax money collected for Social Security for other spending. As a result, politicians didn’t have to borrow as much as they would have, if they hadn’t had access to Social Security money. But that’s no reason to claim that Social Security payments going forward are not going to increase the deficit. They will. If payments don’t decrease, it will be because taxpayers get taxed for benefits all over again.

Veronique de Rugy discusses the vulnerabilities of the Social Security Trust Fund in a Mercatus On Policy.