- | Government Spending Government Spending

- | Policy Briefs Policy Briefs

- |

A Tale of Two Labor Markets: Government Spending's Impact on Virginia

Virginia’s labor market is more troubled than its unemployment rate suggests. If labor force participation were at its 2007 level, the state’s unemployment rate would be as high as 8.6 percent. We estimate that 10 percent of Virginia’s workforce is indirectly employed by the federal government via federal contract expenditures. Excluding these jobs, private job loss in Virginia since 2007 is on par with the national average.

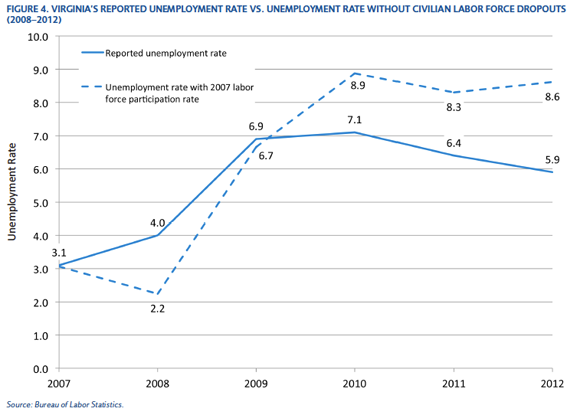

In the aggregate, Virginia weathered the Great Recession and the dismal recovery much better than the nation as a whole. However, the state has two distinct labor markets: a fully private one and a second one that is both directly and indirectly supported by government spending. We estimate that about 30 percent of state employment relies on government spending, and this portion of the labor market flourished during the recession. The remaining 70 percent of Virginia’s labor market has performed about as poorly as the rest of the country since 2007. This poor performance includes a significant amount of worker disengagement that has driven down the official unemployment rate for the state by as much as 2.6 percentage points, giving an impression of a labor market that is healthier than it actually is. Eliminating Virginia’s corporate income tax, reforming the personal income tax, lowering regulatory burdens on low-income entrepreneurs, and eliminating the state’s wasteful sales tax loopholes and enterprise zone program would create opportunities for increased private-sector growth and employment.

THE GREAT RECESSION’S IMPACT ON VIRGINIA

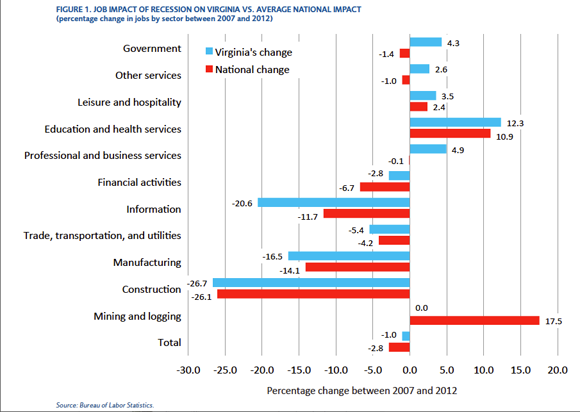

Virginia fared better in the Great Recession than the nation as a whole. In 2012, the state’s unemployment rate was 5.9 percent, compared to a national rate of 8.1 percent.1 At the end of 2012, Virginia had 1.0 percent fewer jobs than before the recession began, while the United States had 2.8 percent fewer (see figure 1). Thirty percent of Virginia’s jobs are in four sectors— construction; manufacturing; trade, transportation, and utilities; and information—which have recovered at a slower rate than the national average.2 However, this underperformance has been offset in large part by Virginia’s government sector and professional and business services sector, which combined make up 37 percent of the state’s labor market but have grown at rates faster than the national average.3 Virginia’s disproportionate reliance on federal government spending helps explain the growth in these sectors and the state’s outperformance of the national labor market during the recovery.

A Tale of Two Labor Markets

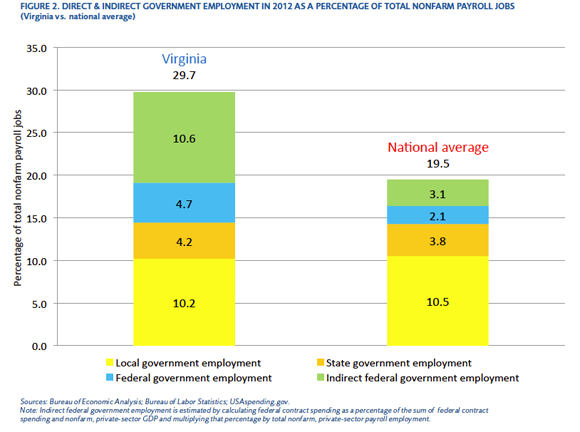

High federal government expenditures in Virginia—which are over double the national average as a percentage of GDP4—boost direct federal government employment in the state. Federal government employees make up over twice as much of Virginia’s labor market as they do of the national labor market (see figure 2). Indirect federal government employment—private nonfarm employment funded by federal contracts—plays an even larger role in Virginia’s labor market. More federal contracts are awarded to firms in Virginia than to firms in any other state, and federal contracts account for over 12 percent of Virginia’s economy, compared to less than 4 percent for the nation as a whole.5 Since 2007 the total value of these contracts has risen by 18 percent—from $46.4 billion to $54.8 billion—compared to a 9.3 percent increase in the rest of the country.6 As a result, indirect federal government employment likely makes up about 10.6 percent of Virginia’s labor market, over three times more than the national average (see figure 2).7 Both direct government and indirect federal government employment in Virginia were higher in 2012 than before the recession.8 Combined, direct government employment and indirect federal government employment account for almost 30 percent of jobs in Virginia (see figure 2).

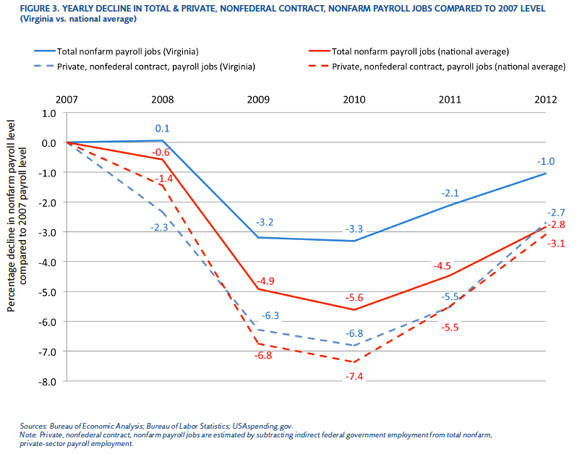

The other 70 percent of Virginia’s labor market—Virginia’s “real” private sector—suffered almost as much damage as the national labor market from the Great Recession (see figure 3). Between 2007 and 2012, private nonfarm payroll jobs excluding indirect federal government employment decreased by 2.7 percent in Virginia, compared to 3.1 percent nationwide. Like the rest of the country, Virginia has also experienced substantial labor force disengagement. If Virginia’s labor force participation rate had remained at its 2007 level, the state’s 2012 unemployment rate would be as high as 8.6 percent instead of 5.9 percent (see figure 4).

The malaise of Virginia’s “real” private-sector labor market has not been experienced equally across Virginia. More than 75 percent of federal contracts awarded in Virginia go to firms in Northern Virginia,9 and this geographically skewed distribution helps explain the disparity in unemployment rates between Northern Virginia and the rest of the state. At the end of 2012, Northern Virginia’s unemployment rate was 4.4 percent, while the rest of Virginia’s was 6.6 percent.10 The difference is even more pronounced when comparing Northern Virginia to some of the state’s most economically distressed regions. In 2012, 9 of the 15 counties and cities in Northern Virginia received over $10,300 in contract awards per worker, while 26 of the 29 counties and cities in Southwestern Virginia and Southside Virginia received less than $2,100 per worker.11 Southwestern Virginia’s 2012 unemployment rate was 8.3 percent and Southside Virginia’s was 8.9 percent.12

Sequestration and Virginia

The effect of sequestration—an estimated decrease in the 10-year growth rate of total federal spending from 72 to 68 percent that began in March 201313—on Virginia’s labor market appears negligible so far. Since January, about 26,100 new private-sector jobs have been created in Virginia and only about 2,700 federal government jobs have been lost.14 Virginia’s overall pace of job growth in 2013 has been about the same as in each of the last three years and its unemployment rate in July was 5.7 percent, about the same as at the end of 2012.15 Total federal spending is estimated to increase by 1.8 percent between 2013 and 2014 and grow every year for the next decade.16 Defense spending—which makes up 68 percent of federal contracts in Virginia17—is estimated to rise every year from 2014 to 2023.18 However, the nation’s record federal debt—combined with sequestration’s lack of real spending cuts—will likely necessitate more serious decreases in federal spending in coming years. To diversify its labor market away from an unsustainable reliance on federal government expenditures, Virginia needs stronger private-sector economic growth.

A Better Path Forward for Virginia

Virginia’s business environment has become less competitive in recent years. According to the Tax Foundation, Virginia had the 19th most friendly tax climate for businesses in 2006, but today it has fallen to the 27th—worse than neighboring Kentucky and Tennessee.19 Between 2007 and 2013, Virginia’s regulatory burden—as calculated by the Mercatus Center’s Freedom in the 50 States index—fell from 3rd best in the country to 9th place.20 Improving Virginia’s tax and regulatory competitiveness will encourage the private-sector economic growth necessary to diversify and expand Virginia’s labor market.

Reducing or eliminating Virginia’s 6 percent corporate income tax would improve the state’s competitiveness. Corporate income taxes have a highly negative effect on economic growth.21 Reducing the rate by just 1 percent can increase annual GDP growth by 0.1 to 0.2 percent.22 Economic research shows that reducing corporate tax rates is revenue-neutral.23 The tax accounts for just 2 percent of total state revenues, so eliminating it is fiscally feasible.24

Virginia’s personal income tax is the 38th most burdensome in the country—worse than neighboring Kentucky and Tennessee.25 The top two marginal rates of 5.00 and 5.75 percent for annual adjusted gross income, which apply to over 85 percent of Virginia households filing tax returns, could be lowered to improve competitiveness.26 Research indicates that doing so would lead to increased economic growth.27 Economists Karel Mertens and Morten O. Ravn find that a one percentage point decrease in personal income tax rates leads to as much as a 0.8 percent increase in employment within one and a half years.28

Eliminating or reducing some of Virginia’s roughly 100 sales tax exemptions29 would help offset the cost of lowering the personal income tax rate. A recent study finds that the value of these exemptions—excluding exemptions that pertain to business-to-business transactions or prevent double taxation—equals almost $5.3 billion.30 Many of these exemptions provide targeted industries with substantial tax advantages and are thus “subsidies in disguise” that harm economic growth.31

Similarly, eliminating the Virginia Enterprise Zone Program (VEZP) could also boost economic growth. VEZP provides grants to firms that create jobs or make real estate investments above arbitrary wage and investment thresholds in high-unemployment “enterprise zones” (EZs).32 These arbitrary zones and award standards benefit larger firms with the resources to apply for and meet the application standards of EZ grants.33 For example, recent grant recipients include Amazon, BAE Systems, Rolls-Royce, and Bank of America.34 Although firms that access VEZP’s grants do create jobs,35 economic research shows that EZs themselves have no impact on employment levels and may even harm employment growth.36 The economic gains of privileged firms that receive grants are offset by economic waste, as well as losses to firms outside EZs. EZs stunt economic growth by incentivizing firms to spend resources chasing grants (a form of government-granted privilege), resulting in economic waste at the expense of consumers and taxpayers.37

Instead of VEZP, scaling back occupational licensing regulations would more effectively encourage job creation in Virginia’s high-unemployment areas. The Mercatus Center’s Freedom in the 50 States index finds that Virginia’s occupational licensing regulations harm the state’s regulatory competitiveness.38 According to the Institute for Justice, these regulations are the 8th most burdensome in the country, with 46 out of 102 low-income jobs requiring a license in Virginia.39 The average licensed profession in Virginia requires over 15 months of education and experience and $153 in fees.40 Occupational licensing regulations harm employment growth and disproportionately burden low-income individuals.41 To encourage entrepreneurship and reduce unemployment, the number and severity of licensing regulations should be reduced and brought in line with requirements in states like Colorado and Pennsylvania.42 Doing this would increase employment opportunities in occupations “ideal for new small business creation.”43

Conclusion

Virginia’s labor market is more troubled than its unemployment rate suggests. If labor force participation were at its 2007 level, the state’s unemployment rate would be as high as 8.6 percent. We estimate that 10 percent of Virginia’s workforce is indirectly employed by the federal government via federal contract expenditures. Excluding these jobs, private job loss in Virginia since 2007 is on par with the national average. While federal spending has softened the economic downturn in Virginia, it poses a long-term threat because the state’s labor market relies heavily on unsustainable federal spending. Virginia should diversify its labor market away from relying on federal support, especially in light of looming federal spending cuts. In order to achieve this diversification, Virginia’s tax and regulatory competitiveness must improve and wasteful special-interest grants and loopholes should be eliminated. These reforms would facilitate the economic growth necessary to increase Virginia’s private-sector employment.