- | Government Spending Government Spending

- | Data Visualizations Data Visualizations

- |

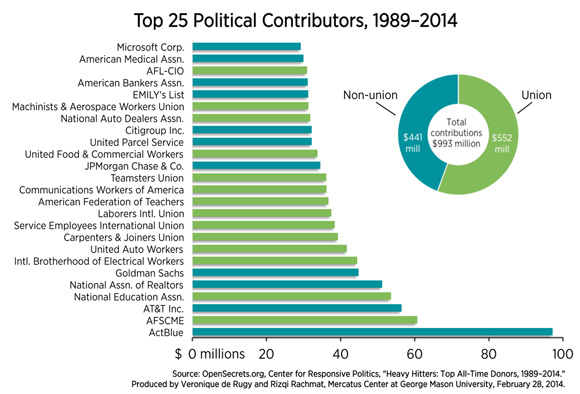

Top 25 Political Donations from 1989 to 2014

The incentives to use political connections for personal gain grow as the power of government grows. Donating to political campaigns is one way that private interests try to win alliances of government authorities. Over the past 25 years, several of the top political contributors have sought political privilege largely under the radar, with some surprising names appearing among the top 25.

The incentives to use political connections for personal gain grow as the power of government grows. Donating to political campaigns is one way that private interests try to win alliances of government authorities. Over the past 25 years, several of the top political contributors have sought political privilege largely under the radar, with some surprising names appearing among the top 25.

This week’s chart uses data from the Center for Responsive Politics’ OpenSecrets.org database to display the top political donors from 1989 to 2014, along with their total donations. Here are some highlights for the period:

- About $1 billion flowed into campaign contributions between 1989 and 2014.

- The top donor is ActBlue, an online political action committee dedicated to raising funds for Democrats.

- Fourteen labor unions were among the top 25 political campaign contributors.

- Three public sector unions were among the fourteen: the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees; the National Education Association; and the American Federation of Teachers. Their combined contributions amount to $150 million dollars, or 15 percent of total donations, since 1989.

- Public and private sector unions contributed 55.6 percent, or $552 million, of all campaign contributions.

- Large private companies contributed $441 million in campaign contributions. Among them were an assortment of banks and insurance firms such as JPMorgan Chase, trade associations such as the National Association of Realtors and American Medical Association, and technology and telecommunications companies such as AT&T and Microsoft.

To have a complete picture of the landscape of political influence, we must be aware of the disparate special interests that compete for government granted privileges such as bailouts, protections, subsidies, regulations, and tax breaks.

Large campaign contributions from any group are fair grounds for scrutiny, regardless of whether those funds were initiated by AT&T or the Service Employees International Union. It should give us pause when we consider the sizeable political contributions coming from the financial industry in the wake of, and perhaps future prospects for, bank bailouts.

The same goes for privileges sought by public-sector unions. In 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a champion of worker’s rights and collective bargaining, noted that “meticulous attention should be paid to the special relationships and obligations of public servants to the public itself and to the Government.”

Public-sector employees are accountable to the public—to “We, the People”—but their unions manage the government on our behalf. It is for this very reason that public-sector unions present a real problem in representing both sides of the negotiating table—for their own benefit. In this sense, they harbor a special conflict of interest that sets them apart from private companies, private unions, and trade organizations.

As my colleague Matthew Mitchell has observed, “When governments dispense privileges, smart, hardworking, and creative people are encouraged to spend their time devising new ways to obtain favors instead of new ways to create value for customers. Privileges depress long-run economic growth and threaten short-run macroeconomic stability. They even undermine cultural mores, fostering cronyism, blurring the distinction between productive and unproductive entrepreneurship, and eroding people’s trust in both business and government.”

If we want to restore real economic growth and eliminate the cronyism associated with political privilege, we must first address the issue of privilege granting and seeking.