Dealers wasted no time petitioning Congress to reverse the planned dealer terminations. The 2010 Consolidated Appropriations Act (H.R. 3288) included a provision, Section 747, which provided the opportunity for “covered dealerships” to reacquire franchises terminated on or before April 29, 2009 through an arbitration process. The provision affected all 2,789 dealerships slated for termination; however, the total count of dealers who decided to file paperwork to enter the process was 1,575. Of the cases that went to hearings, arbitrators allowed the manufacturers to close 111 dealerships and ruled in favor of 55 dealers. The other cases were settled or withdrawn.

Virtually all states require auto manufacturers to sell new vehicles through local franchised dealers, protect dealers from competition in Relevant Market Areas (RMAs), and terminate franchises with existing dealers only after proving they have a “good cause” to do so. These state laws harm consumers by insulating dealers from competition and forestalling experimentation with new business models for auto retailing in the twenty-first century. A pro-consumer policy would make franchising, exclusive territories, and termination protections voluntary rather than mandatory. Under voluntary contracting, these business practices could still survive when their benefits to consumers exceed the costs.

The Ubiquity of Dealer Protection Laws

The first automobile franchise was established by William Metzger, who purchased the right to sell steam engine cars by General Motors in 1898.1 What started as a voluntary agreement between a manufacturer and a retailer has turned into a mandatory requirement in all 50 states and in US territories.2 State auto franchise laws extensively regulate the contractual obligations between manufacturers and dealers. They prevent manufacturers from selling new vehicles (and related services) directly to the public, often mandate exclusive territories for dealers, and make it difficult for manufacturers to terminate dealers.

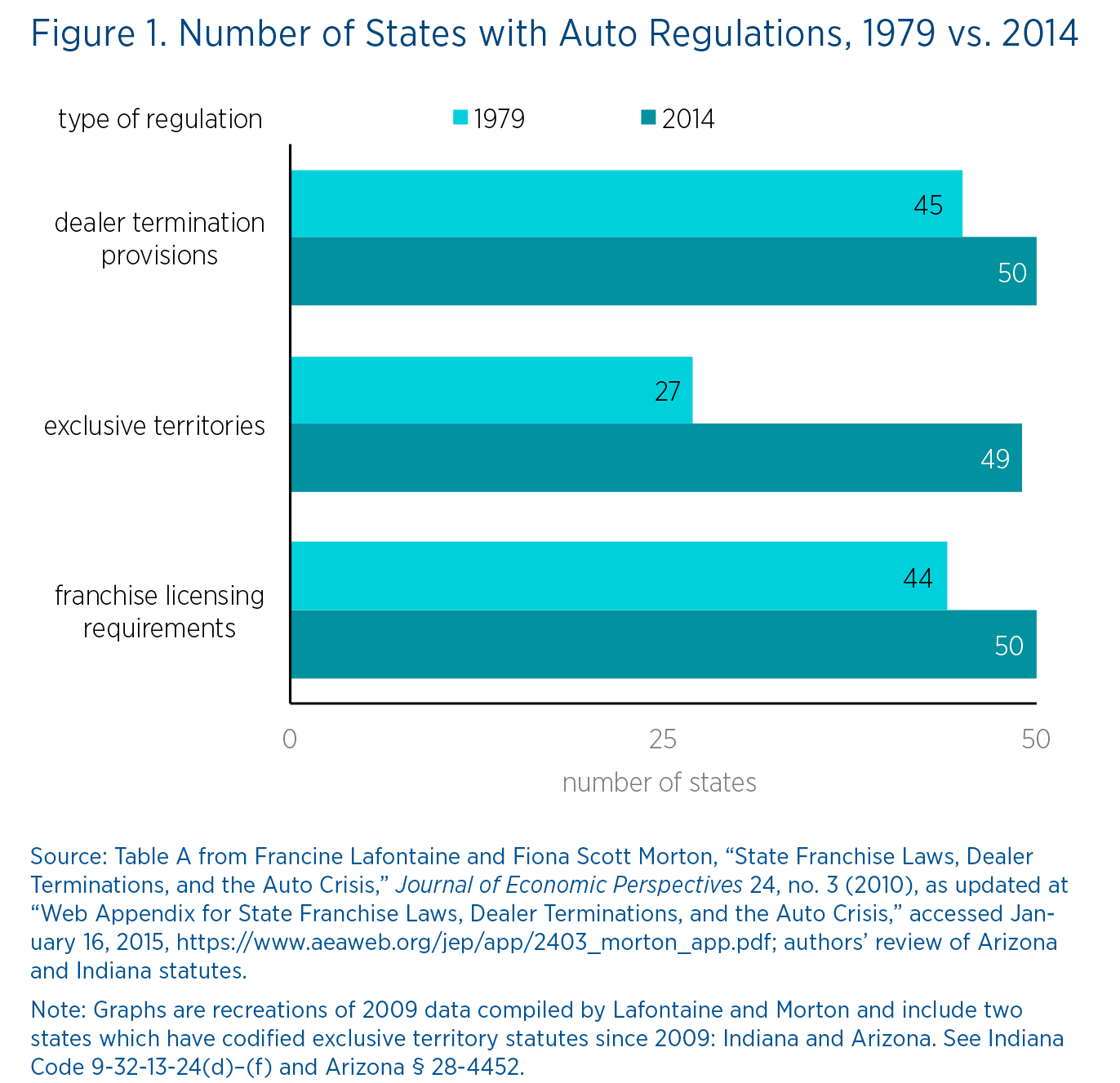

State auto franchising regulations have become ubiquitous during the past three decades. As figure 1 shows, all three types of laws—franchise licensing requirements, exclusive territories, and dealer termination provisions—became more common between 1979 and 2014. During those 30 years, states enacted 31 new laws on those topics. In 1979, fewer than half of all states regulated all three aspects mentioned above. By 2014, all but one state regulated every single one of these aspects.

Recent Controversies over Dealer Protection Laws

Although states have ramped up dealer protection, two recent policy controversies have called these laws into question. Electric automaker Tesla has sought to sell automobiles directly to the public, and federal supervisors of the Chrysler and General Motors bailout pressured the automakers to terminate numerous dealerships.

Tesla: Uprooting the Traditional Franchise System

Tesla’s direct sales model runs completely counter to the traditional franchise model: Tesla (in states where it has been granted statutory exceptions to operate)3 manufactures, prices, and services its own cars. CEO Elon Musk is betting that Tesla employees can learn about the car’s new technology and sell more effectively than traditional independent dealers paid on commission.4 Regardless of whether he’s right, so far state laws prevent him from finding out. Tesla’s reluctance to operate franchises has led to legislative battles with states across the nation, including Michigan, New Jersey, Arizona, and West Virginia.5

Dealer Terminations after the 2008 Financial Crisis

The recession following the 2008 financial crisis highlighted the troubled relationship between US auto manufacturers and franchise dealers. New vehicle sales plummeted from 16,460,315 in 2007 to just 13,493,192 in 2008.6 Following the imminent financial insolvency of Chrysler and GM, President Bush authorized emergency funding under the Troubled Asset Relief Program to aid the auto industry. The Obama administration further stipulated that these funds would only be released if Chrysler and GM restructured their operations to achieve “long-term viability.”7

The administration woefully underappreciated the complexity of the manufacturer-dealer relationship. Chrysler’s final restructuring plans submitted to the president’s Auto Task Force called for shedding 789 dealers, while General Motors planned to cut more than 1,100 dealerships.8 Chrysler and GM claimed that these dealers were unproductive and unprofitable.9

Dealers wasted no time petitioning Congress to reverse the planned dealer terminations. The 2010 Consolidated Appropriations Act (H.R. 3288) included a provision, Section 747, which provided the opportunity for “covered dealerships” to reacquire franchises terminated on or before April 29, 2009 through an arbitration process.10 The provision affected all 2,789 dealerships slated for termination; however, the total count of dealers who decided to file paperwork to enter the process was 1,575. Of the cases that went to hearings, arbitrators allowed the manufacturers to close 111 dealerships and ruled in favor of 55 dealers. The other cases were settled or withdrawn.11

Dealer Protection: Voluntary vs. Mandatory

The state-mandated restrictions in new car markets are part of a larger class of business arrangements between producers and retailers known as “vertical restraints.” Economic research finds that voluntarily adopted vertical restraints often benefit consumers, but state-mandated vertical restraints virtually always harm consumers.12

Benefits of Voluntary Vertical Restraints

Franchising, exclusive territories, and dealer protection from termination can benefit consumers when they are adopted voluntarily by manufacturers and dealers. Auto dealers provide valuable services to consumers that some manufacturers are unwilling or unable to provide. These services include holding inventory, offering test drives, accepting trade-ins, and auto servicing and maintenance.

By contracting with franchised dealers instead of opening dealerships with their own employees, automakers create a powerful profit incentive for dealerships to undertake these efforts. Exclusive territories can further encourage dealers to invest in sales and service efforts by making it harder for consumers to visit a high-service dealer to learn about the vehicle but then buy it from a low-service dealer who can offer a lower price because he has not made a similar investment in sales and service efforts. Restrictions on termination can also spur dealer investment in both physical location and customer service by removing the risk that the manufacturer will demand further concessions from the dealer after the dealer has made the investments. Dealer sales and service efforts do not just benefit manufacturers; they also benefit consumers.13

Costs of Mandatory Vertical Restraints

When franchising, exclusive territories, and restrictions on termination become mandatory, however, manufacturers can no longer adopt other business models if circumstances change. Consumers suffer higher prices and less convenience as a result. Since most states now have these laws, it is difficult to estimate their effects by comparing prices in states with and without the laws. A study using data from 1972, when fewer states imposed these restrictions, found that the combined effect of all state auto franchise restrictions was to raise new car prices by about 9 percent.14

Preventing Direct Sales: Mandatory Franchising

Since state laws require manufacturers to sell new vehicles through franchised dealers, manufacturers cannot sell directly to the public.15 This requirement prevents new manufacturers, such as Tesla, from establishing factory-owned dealerships.

Tesla’s direct sales model could improve the dealership experience for consumers interested in purchasing an electric vehicle. A McKinsey analysis of the auto industry estimates the percentage of consumers who purchased a new vehicle and left the dealer dissatisfied with their experience at a relatively low 25 percent.16 Researchers at the UC Davis Institute of Transportation Studies, however, found that 83 percent of customers in California who purchased an electric vehicle were dissatisfied with their dealer experience.17 While it may work fine for many customers buying traditional vehicles, the franchise system may not provide a satisfactory experience for a significant number of consumers hoping to purchase an electric vehicle.

Mandatory franchising also prevents established manufacturers from selling directly to the segment of consumers who might prefer to avoid the dealership and simply order a car from the manufacturer, the same way many consumers buy built-to-order computers from manufacturers. Gary Lapidus, formerly a US auto industry analyst for Goldman Sachs, estimated that a build-to-order system could save consumers $2,225 on the price of a new car, based on an average price of $26,000 per car.18 A position paper prepared for the National Automobile Dealers Association (NADA) disputes this figure, labeling it “a math exercise that assumed that such expenses would vanish in a direct distribution model.”19 Since manufacturer direct sales are illegal in all 50 states, neither manufacturers nor consumers have the opportunity to find out.

Finally, in some states mandatory franchising bars manufacturers from direct sales of used vehicles, direct financing of car purchases, or even direct sales of simple accessories.20 For example, a shopper who wants to buy a Ford-branded locking gas tank cap or trunk cargo organizer at the ford.com web site is furnished with a “suggested retail price” and must input a zip code to find a local dealership from which to purchase the item.21

Restricting New Dealerships: Relevant Market Areas

Relevant Market Areas (RMAs) grant a dealer or group of dealers exclusive territorial rights by preventing the manufacturer from establishing additional dealerships within a given geographical area. In some cases, manufacturers and dealers may both find RMAs in their interest because they encourage dealers to invest in promotion of the brand. RMAs are mandated by law in every state except for Maryland, where dealerships only have the opportunity to file lawsuits against manufacturers to determine whether a “performance standard or program” based on “demographic” or “geographic” characteristics is unfair or unreasonable.22 These statutes provide dealerships with exclusive territories and require manufacturers to prove a “need” for establishing a new dealership within such an area.23

RMA statutes help insulate dealers from competition. Without the threat that the manufacturer might open other competing franchises, existing dealers have the opportunity to charge consumers higher prices.24 Since almost all states now have RMA laws, it is difficult to estimate how RMAs affect prices today. In the mid-1980s, when RMAs were less prevalent, Federal Trade Commission economists estimated that they increased the price of new cars by approximately 6 percent.25 The percentage is arguably lower now, because the Internet has increased competition between dealers. A 2001 study found that Internet referral services save consumers about 2 percent on new car purchases26—a figure consistent with the hypothesis that the Internet has reduced, but not eliminated, the price-increasing effects of RMA laws.

Inflating the Cost of Dealership Networks: Termination Laws

Another legal protection provided to dealerships is restrictions on dealer terminations. Currently, every state has laws preventing dealership terminations except for “good cause.”27 The definition of “good cause” varies by state, but it usually focuses on factors like a dealer’s conviction for a felony, fraud, insolvency, or failure to comply with a material term of the franchise agreement. States do not typically regard a manufacturer’s desire to improve the efficiency of its dealer network as “good cause” to terminate dealers. Moreover, once a manufacturer has explained its “good cause,” many termination laws also give the dealership a period of time (often 180 days) to correct the error.28

The arbitration process does not appear to have neatly resolved the issue of dealership terminations following the auto bailouts. Chrysler continues to deal with lawsuits from dealerships that closed following bankruptcy.29 It is also worth noting that the bulk of cases were settled, which often entailed either reinstatement or monetary compensation.30

In the latter part of the twentieth century, state laws inhibited the Big Three US automakers from restructuring their dealership networks as Americans moved from the cities to the suburbs, migrated from the Northeast to the South and Southwest, and started buying vehicles from foreign manufacturers. Foreign manufacturers were less hampered by dealer termination laws because they did not enter the US market and establish their dealer networks until the 1970s.31 While we don’t know what the optimal dealership network is, research suggests that auto manufacturers with fewer dealerships require significantly fewer days of inventory, which can reduce costs substantially.32

Changing Times: Can the industry get back “on the road again?”

Dealer protection laws effectively freeze the retail network. Mandatory restrictions make it difficult for manufacturers to experiment with new methods of auto sales or to close unprofitable and inefficient dealerships, which ultimately prevents any potential cost savings to consumers. And auto dealers vigorously defend these privileges. In a report that noted dealers earned record profits during the past year, a consulting firm that assists in the purchase and sale of dealerships sounded the call to arms:

Since we are supporters of the franchise system that is working so well for all of us, we encourage our dealer friends, particularly those who own luxury stores, to lobby heavily to enforce the state laws that protect local dealers from factory owned dealerships. Customers will want to own Teslas, so maybe the best course of action would be to try to compel Tesla to award franchises to entrepreneurs just as all the other [original equipment manufacturers] have done.33

In short, state auto franchise regulations institutionalize anticompetitive pathologies.34 We do not claim to know the optimal way of organizing auto distribution and retailing for the industry as a whole or any individual automaker. NADA’s previously mentioned position paper argues strenuously that the current system of franchised dealers will always out-compete a system of manufacturer-owned dealerships.35 If this is true, the current franchise system should not need the legal protection it enjoys in every state.