- | International Freedom and Trade International Freedom and Trade

- | Policy Briefs Policy Briefs

- |

The Case for and against a Policy of Unilateral Trade Liberalization

Ever since Adam Smith first put quill to parchment on the matter almost 250 years ago, many economists have not only sung the praises of free trade, they have also supported a policy of unilateral free trade. Proponents of unilateralism argue that the economic well-being of a country’s people rises the more they are allowed by their own government to trade freely with foreigners regardless of the economic policies pursued by foreign governments. Here, for example, is Paul Krugman writing in 1997: “The economist’s case for free trade is essentially a unilateral case: a country serves its own interests by pursuing free trade regardless of what other countries may do. Or, as Frederic Bastiat put it, it makes no more sense to be protectionist because other countries have tariffs than it would to block up our harbors because other countries have rocky coasts.”

And yet relatively few people have been persuaded that free trade is a policy that should be followed unilaterally. While many governments over the past 75 years have lowered their trade barriers, much of that liberalization was the result of trade deals in which each government agreed to lower its barriers only on the condition that other governments lowered theirs.

Proponents of unilateralism applaud the trade liberalization that has occurred since World War II as a result of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, its successor, the World Trade Organization, and other regional and bilateral trade deals. Yet liberalizing trade in this way is, from the perspective of unilateralists, a second-best, unnecessarily costly, and time-consuming option when compared with a policy of unilateral free trade. What explains the fundamental difference between proponents and detractors of unilateral trade liberalization?

Game theory can help one understand this difference. My goal here is to offer neither new theory nor new data. Instead, I aim only to identify and describe a logic plausibly held by those who oppose unilateral free trade and to compare this logic with that held by proponents of unilateralism, including a large number of economists. In doing so, I hope also to debunk some myths widely believed by opponents of a policy of unilateral free trade.

The hypothetical example used here is of two countries that trade—or can potentially trade—with each other. In the figures that follow, China is displayed in red, and the United States is displayed in blue. Each government has the choice of following a policy of free trade or protectionism. By “free trade,” I mean the absence of government-erected barriers to citizens’ freedom to import goods and services from the other country and the absence of government-granted subsidies to exporters. By “protectionism,” I mean the implementation of some such significant obstruction of citizens’ freedom to trade, the use of subsidies, or both. There is, however, nothing special about this two-country model; it is used only for expositional ease. The logic of this model applies to the real world of nearly 200 countries.

In the next section, I describe a common understanding of the gains of trade. I will show how this rationale led to trade liberalization in the roughly 75 years following World War II. Following that, I describe the core logic of unilateralists, and the final section deals with some complications.

A (Mis)understanding of Trade

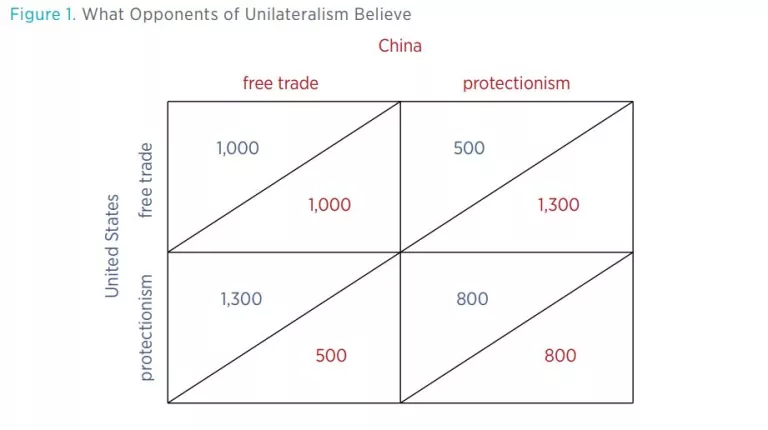

Figure 1 shows a common rationale for international trade. The numbers in each cell show each country’s economic well-being as it is conventionally understood in the context of trade. The reader may for convenience think of these numbers as dollar figures, but note that the absolute values of these numbers are irrelevant; all that matters is the value of each number compared to that of any of the others.

Given this set of beliefs, a country—say, China—concludes that it will make itself better off by imposing protectionism if the other country—say, the United States—is a unilateral free trader. By using protectionism, China “protects” itself from (what it believes to be) costly, jobs-destroying imports while the resulting damage to its valuable export trade is relatively modest. China believes that, on net, it gains from its protectionism. In figure 1, China’s welfare is believed by Chinese leaders (and perhaps also by the Chinese people) to rise from 1,000 (in the northwestern cell) to 1,300 (in the northeastern cell) when China adopts a policy of protectionism.

Because government officials tend to believe that trade works as shown in figure 1, each country obviously has an incentive to defect from a policy of free trade if it believes that the other country will continue to follow a policy of free trade (that is, if it believes that the other country is committed to a policy of unilateral free trade).

But if the payouts of trade were as those shown in figure 1, then no country would be a unilateral free trader. If China defects from free trade, US leaders believe that the result is a significant loss for America: America’s ability to export is believed to be severely restricted while it continues to receive, without restriction, (what it believes to be) costly, jobs-destroying imports. A rational US response, in these circumstances and with this belief system, is to retaliate against China’s protectionism with protectionism of its own. By reducing China’s exports, US protectionism diminishes the damage suffered by Americans from imports from China and inflicts on China substantial costs comparable to the costs that China’s move to protectionism inflicts on the United States.

The world winds up in figure 1’s southeastern cell. This outcome is not only the worst of all possible outcomes for the world as a whole, it is also a worse outcome for each individual country compared with the outcome in the northwestern cell, the outcome with mutual free trade. Yet given their beliefs about the way trade works, neither country has an incentive on its own to adopt a policy of free trade unilaterally.

Nevertheless, if both countries wish to improve as much as possible their people’s economic well-being, then, within the framework of figure 1, the best way to do that is to mutually agree to make trade freer. China will abandon protectionism on condition that America does so, while America will abandon protectionism on condition that China does so. The result is a move from the southeastern cell to the northwestern cell.

The outcome of mutual free trade for each country, however, is not the best possible: the benefit enjoyed by a country under mutual free trade is less than the benefit that country would enjoy if it could use protectionism without prompting the other country to retaliate. But because the other country will retaliate and thus move the world to figure 1’s southeastern cell, the best practical, sustainable option for each country is to mutually agree to move toward free trade.

This highly simplified game-theoretic account adequately captures the logic that fueled the great post–WWII trade liberalization. Countries granted to each other the “concession” of allowing their citizens greater access to imports in exchange for the benefit of being better able to export. Trade unilateralists applaud this outcome. However, they believe this outcome to be, compared with a policy of unilateral free trade, “second-best”—the result of an unnecessarily costly and time-consuming process, and one that, as the events of the past three or four years make plain, fails to make free trade as secure as it would be if there were a more widespread acceptance of the unilateralists’ understanding of trade.

Trade Unilateralists’ Understanding of Trade

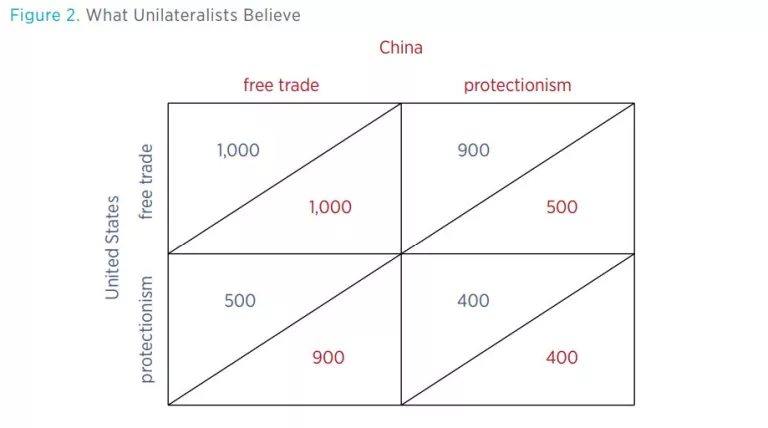

Figure 2 shows the logic of trade as understood by unilateralists. This understanding differs greatly from the foregoing rationale. Specifically, unilateralists believe that the benefits that each country gains from trading are its imports while the costs of obtaining these gains are its exports. This reality is obvious when explicitly stated: exports are things that citizens of the home country give up, whereas imports are things that citizens of the home country receive. Imports, in effect, are purchased with exports. Thus, the greater is the amount (measured in value) of imports received in exchange for some given amount of exports, the greater are the home country’s gains from international trade.

At its core, the case for international trade rests on the well-established fact that each country gains by trading with the other. As in figure 1, if both countries follow a policy of free trade (as shown in the northwestern cell), each country is better off than if both countries are protectionist (as shown in the southeastern cell). Also, as in figure 1, for both countries taken together, mutual free trade is the best policy compared with any of the other combinations of policies.

In addition, and also as in figure 1, precisely because each country gains by trading with the other, if one of the countries abandons free trade in favor of protectionism, some of the resulting economic loss falls on its trading partner. Unilateralists are not blind to this reality. But unlike their critics, they believe that the bulk of the harm suffered by a government’s protectionist policies falls on that government’s own citizens. Figure 2, unlike figure 1, reflects this conclusion, one supported by more than two centuries of economic research. Figure 2 reveals the rationale for supporting a policy of unilateral free trade.

Looking at figure 2, suppose China were to defect from free trade by adopting protectionism (that is, by moving from the northwestern cell to the northeastern cell). The first fact to note is that, contrary to nonunilateralists’ understanding of trade, unilateralists are convinced that China would lose, not gain, even if America continues to trade freely. A second and more relevant fact is that, also contrary to conventional understanding of trade, America would lose if it retaliates against China’s protectionism with its own protectionism (that is, by moving from the northeastern cell to the southeastern cell).

Some Complications

But the analysis so far has not yet firmly settled the matter in favor of a policy of unilateral free trade. Protectionists will respond by correctly noting that figure 2 shows only the outcome for a single period. According to protectionists, the logic of figure 2 is too static; it fails to account for how each country might respond in subsequent periods to a change in the current period of the other-country’s trade policy.

Protectionists point out that the loss suffered today by America as a result of its retaliatory tariffs can be more than compensated tomorrow if these tariffs persuade the Chinese to return to free trade. By enduring a self-inflicted loss today of 500, as shown in figure 2 by a move from the northeastern cell to the southeastern cell, Americans can, through retaliatory tariffs, inflict losses also on the Chinese (of 100). If the Chinese react to these losses by returning to free trade, America can then remove its retaliatory tariffs and each country would enjoy, period after period, economic welfare of 1,000. Americans’ stream of future gains that result from using tariffs to pressure China to return to free trade might well be greater than the losses America suffers today in consequence of those retaliatory tariffs.

That it is possible for retaliatory tariffs to work in this happy fashion (that is, to promote what Adam Smith described as the “recovery of a great foreign market” in a way that proves over the long-run to be beneficial to the home country) cannot be denied. But careful consideration of figure 2 reveals that this outcome, although possible, is improbable.

By originally moving from free trade to protectionism, the Chinese government reveals either a willingness to have its country suffer economic losses or an obliviousness to these losses. Either way, it’s doubtful that the additional losses inflicted on China as a result of US imposition of retaliatory tariffs—losses that are smaller than the losses that China suffers as a result of its own protectionism—would prompt Beijing to return to a policy of free trade. If Beijing doesn’t notice or doesn’t mind the costs that its own protectionism imposes on the Chinese people, there’s good reason to doubt that Beijing will notice or mind the additional, smaller costs that US protectionism imposes on the Chinese people.

Again, it cannot be denied, as a matter of logic, that the additional losses that China suffers as a result of US retaliation might be the straw that breaks the camel’s back and, thus, persuades Beijing to adopt free trade. Yet the fact that the losses that a foreign country’s retaliation imposes on the domestic economy are less than are the losses that that economy suffers as a result of its own protectionism is a sound reason in practice for skepticism about the efficacy of using retaliatory tariffs as a tool to pressure foreign governments to move toward free trade.

Skepticism about the efficacy of retaliatory tariffs increases if one inquires more deeply into the reason why a government resorts to protectionism in the first place. If that reason is simple obliviousness to the steep costs of its own protectionism, then, as just noted, it’s unlikely that that government will take notice of the additional but smaller costs that its country suffers as result of another country’s protectionism.

But government obliviousness is not a satisfying explanation for protectionist policies. More realistically, each government imposes such policies not because it is oblivious to protectionism’s costs but, instead, because it is highly attentive to the concentrated benefits that its protectionism generates for particular home-country producers. Whereas the total costs to an economy of government protectionism are greater than any benefits, governments are also aware that these costs are widely dispersed while the benefits are concentrated.

This difference in the distribution of costs and benefits gives rise to the familiar special-interest-group effect. When this effect is present in the political arena, those who benefit from a government program have strong incentives to lobby in support of that program while those who pay the program’s costs have weak incentives to lobby against it—meaning that those who capture concentrated benefits have a disproportionate influence over political outcomes. The result can easily be the creation and maintenance of policies that impose net harm on the people of the country.

In reality, each government imposes protectionist policies chiefly because it’s under the influence of special interest groups—the influence, specifically, of the particular producers (firms and workers) who are shielded by protectionist policies from the competition of foreign rivals. Unless retaliatory protectionism somehow reduces the influence of these special interest groups, retaliatory protectionism is unlikely to put sufficient pressure on foreign governments to abandon their protectionist policies.

Yet any general imposition of tariffs in retaliation for foreign-government tariffs has no practical prospect of reducing the power of interest groups abroad. The reason is that the negative consequences suffered abroad from a home country’s retaliatory general hike in tariffs will be spread over many producers. These negative consequences are unlikely to be concentrated on the particular special interest producer groups whose political potency is responsible for the foreign government’s protectionism. Hence, the special interest producer groups who successfully pushed in the first place for tariffs abroad will retain their disproportionate political influence and prevent their government from eliminating the offending tariffs.

For retaliatory tariffs to have any prospect of working, they must be targeted in ways to diminish the power of special interest producer groups abroad. Such targeting would be, in many cases, theoretically possible but impractical.

The difficulty with targeted retaliation is not so much that the home government cannot determine which particular imports from the offending foreign country to target with retaliatory tariffs (although in some cases such difficulty will surely loom large). Instead, for the home government to carry out such surgically precise retaliation would require either that the home government be apolitical or that the retaliatory tariffs that are likely to be effective happen to promote the interests of special interest groups in the home country.

One can dismiss immediately any possibility that the home government is apolitical. One is then left only with the hope that the appropriate targeted retaliatory tariffs happen not to threaten the welfare of special interest groups in the home country—one might hope specifically, for example, that the tariffs are not imposed on inputs that domestic producers import in large quantities. Although such a hope might, from time to time, be realized, it is imprudent to reject a policy of unilateral free trade simply because the home government might occasionally succeed in targeting retaliatory tariffs to possibly make global trade freer.

Skepticism of the effectiveness of retaliatory protectionism grows even more when one recognizes the possibility—which is indeed likely—that the government of a targeted foreign country will respond to the retaliation not with trade liberalization but with its own retaliatory tariffs, ones in addition to its first round of tariffs and now targeted, when possible, to inflict disproportionate harm on influential interest groups in the home country. The result is a trade war, and such wars have been quite common historically.

One final reason for wariness of retaliatory protectionism warrants mention: if government retains the discretion to impose retaliatory tariffs, the temptation is great for special interest groups in the home country to portray almost any economic policy pursued by a foreign government as detrimental to the home economy and, thus, as an ostensible justification for home-country retaliatory tariffs. By credibly committing to follow a policy of unilateral free trade, such rent-seeking efforts will be kept to a minimum.

Conclusion

The long-standing and still-prevalent consensus among economists is that (a) protectionist policies in all but the rarest of theoretical cases impose net damage on the home economy and (b) the bulk of the economic damage of any government’s protectionism falls on its own citizens. The logic that leads to these conclusions is depicted in figure 2. These conclusions differ substantially from conventional beliefs about trade, which are depicted in figure 1. Whereas figure 1 shows the conventional misunderstanding of the gains of trade and the consequent reasons for opposing unilateral free trade, figure 2 reveals trade unilateralists’ reasons for supporting it.

As I recognize, economists and others who support a policy of unilateral free trade do not (as is often asserted by protectionists) deny that a foreign government’s protectionism inflicts some damage in the home country. Informed trade unilateralists make no such denial. Nor do they deny the theoretical possibility that retaliatory tariffs could, in theory, cause foreign governments to reduce or even eliminate their tariffs, thus yielding net gains in the home country over the long term. But an economically informed comparison of the magnitude of the damage that foreign-government protectionism has at home with the damage done at home by home-government protectionism casts doubt on the wisdom of retaliation. This doubt is only intensified when one recognizes the interest-group pressures that realistically are almost always at the root of governments’ resort to protectionism—pressures explained well by public choice theory and repeatedly confirmed by history.