Getting Started

As 2024 approaches the midyear mark, we find an economy that has adjusted to the massive 2019–2020 COVID interruptions and stimulus spending and is now reacting primarily to ongoing Federal Reserve (Fed) efforts to reduce inflation by keeping interest rates at a higher level while hoping to avoid a recession. Yes, restaurants are again teeming with customers, air travel has recovered, and retail sales, having rebounded from pandemic difficulties, are strong. But higher interest rates are taking a bite out of equipment investment, real estate sales, and related construction activities, and there are, of course, other major forces affecting the economy. These forces include increased federal spending to support electric vehicle (EV) sales, chip production, clean technologies, and the Ukraine and Middle East wars and their effects on energy prices and US production of war-related materials.[1]

Along with these headline activities, the US economy is energized by historically high levels of new business formation, rising productivity (perhaps fueled in part by explosive growth in the use of artificial intelligence software), and a continuing flow of foreign-born workers filling jobs in the tight US labor market. (In 2022, foreign-born workers accounted for an all-time high of 18.1 percent of the labor force.[2]) And how could we not be aware that it is crazy season in America?—that time every four years when presidential candidates are promising the moon or simply more bread and circuses as they seek to line up votes for the November election.

The tightrope economy

We might describe the current situation as involving a tightrope economy. A policy slipup or sudden shock in either direction could lead to recession, on the one hand, or inflation acceleration on the other. At best, we always see through a glass darkly when we try to understand how the economy may be performing.

In recent weeks, the GDP growth estimate for 2024’s first quarter, along with April employment data, has been received. First-quarter data for real GDP growth of 1.6 percent was well below the 2.4 percent Dow Jones survey expectations and much weaker than the 2023 fourth quarter’s 3.3 percent annual growth rate.[3] Similarly, April employment data showed one of the slowest gains in new jobs in recent months—175,000 versus the 242,000 average for the previous 12 months—while a low 3.9 percent unemployment rate continued apace.[4]

Readers of this newsletter should not have been surprised. Our March report showed expected growth for 2024’s first quarter to range between 0.8 percent and 1.4 percent, as reported by the forecasters we rely on.[5]

The March report’s discussion of the economic outlook ended with the following note:

Despite the strength of consumer spending and a lot of good historical data, higher interest rates are affecting housing and other construction activities. We should see slower growth in the first half of 2024. Some states, because of their strength and population growth, will prosper. Others will feel what seem like local recessions. All of this, coupled with diminishing inflation, suggests it’s finally time for the Fed to gingerly nudge the accelerator. [6]

Inflation, the money supply, and GDP growth

The most recent inflation estimates, for both the Consumer Price Index and the Fed’s preferred Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index, reversed their falling growth rates and moved higher before relaxing a bit, giving understandable heartburn to the Fed and more serious real problems to American consumers who find themselves shopping with dollars that just don’t go quite as far as they used to. Following the Federal Open Market Committee’s May meeting, Fed Chair Jerome Powell indicated that while the Fed was leaving short-term interest rates at the current 5.25 percent level, it was taking actions to ease recent efforts to reduce money supply growth.[7] Powell was referring to the management of the more than $7 trillion in government securities owned by the Fed. These investments reflect past efforts in troubled times to provide the nation’s banking system with additional reserves. Decisions to reinvest in maturing bonds maintain money supply growth at current levels, whereas decisions to reduce bond holdings nudge the money supply in a positive direction.

As pointed out in the March report, money supply growth affects GDP growth and crudely predicts future inflation rates with a lag of more than a year. There are obviously other forces that affect economic activity; still, given past money supply growth, we should continue to see falling inflation and slower GDP growth. In the March report, I also noted that growth in the money supply, M2, just turned positive in March after 16 months of negative growth.[8]

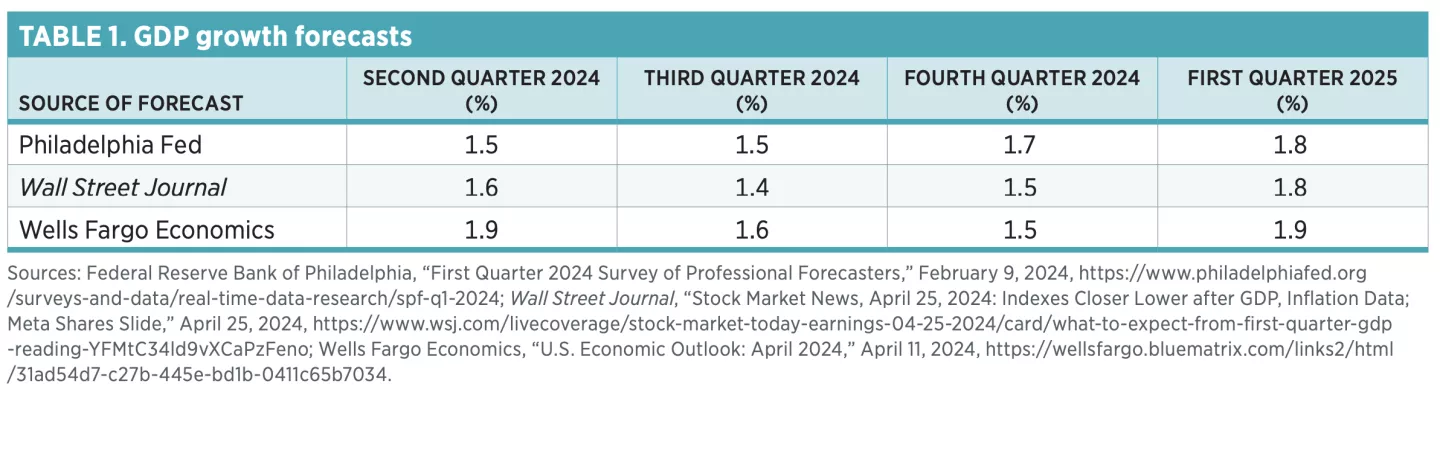

By way of an update, in table 1, I provide GDP growth estimates for the next four quarters from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, the Wall Street Journal, and Wells Fargo Economics. The data in the table suggest that the forecasters are reading the same tea leaves. We should expect below-normal growth for the next four quarters.

I next show two data maps, one for December 2023 and the other for April 2024, provided by the Philadelphia Fed (figure 1). The maps show three-month growth for state coincident indicators. The maps help us visualize regional patterns of economic prosperity. It is noteworthy that the April 2024 map exhibits a much healthier hue overall than the earlier map of December 2023.

How this report is organized

The report has four sections including this introductory section. The next section focuses on the ongoing inflation battle being waged by the Fed and how that battle is reminiscent of the fabled King Canute’s reluctant struggle to control the tides. In the case of inflation, the Fed has practically stopped addressing it, as though inflation is under control, but across town in the White House, President Joe Biden continues to act as though he has the power to turn back the tide. The section suggests that the White House should focus its energies on things that can be accomplished rather than acting as if rising prices will respond to a president’s command.

The third section highlights election year game playing by both political parties and the ongoing effort by politicians to gain ballot box support by doing things for important interest groups. Yes, bread and circuses still seem to be in vogue. The fourth section addresses the question “Are we going to hell in a handbasket?” and happily concludes, on the basis of a multitude of important data, that the outlook may not be as bleak as one might surmise after watching the typical evening news show. No, it may not be morning in America, but the sun is not setting on the good ole USA either—or the world, for that matter.

The report also includes a book review from Yandle’s reading table.

King Canute’s Remedy for Inflation’s High Tides

In recent days,[9] the inflation indicators have stubbornly signaled that a high tide of prices is still soaking us consumers.[10] Growing at a 3.5 percent annual rate in March, the Consumer Price Index has now exceeded expectations for three months hand running.[11] Once again, investors and financial decision makers—and isn’t that everyone with a bank account?—are playing the Federal Reserve guessing game.

What will the Fed and its 500 economists do now?[12] After all, this is an election year. What about President Biden? Is there something the nearly two million civilian employees in the executive branch can do? To Fed Chair Powell, the frustrating and painful combination of interest rate hikes and orchestrated reductions in the money supply may be feeling like King Canute’s fabled attempt to counter an incoming tide.[13]

According to legend, the 11th-century Viking ruler of England, Denmark, and Norway sought to prove to his fawning royal staff that, as much as they wished otherwise, even their king could not control the tides. Canute had his throne moved to the edge of the sea and then ordered the tides to halt and not wet his feet and robes. Of course, the tide paid no attention, and the king retreated to higher ground.

After admonishing his subjects not to expect unyielding forces to obey his commands, Canute proceeded to take other actions that would make life more pleasant. He reduced tariffs and taxes imposed on his people when they made important pilgrimages to Rome and devoted his energies to other beneficial changes, all of which focused on policies that he could actually control.

Reduced expectations for the Fed’s performance

Maybe Fed Chair Powell should admit that the Fed is not able to bring about calculated and systematic reductions in the price level at this time. Unpopular as it may be, perhaps he should note that after the government spending spree that began during the pandemic and continues unabated to this day, the inflation tide will ebb and flow. It seems clear that as long as Congress and the president continue to spend drastically more money than the nation takes in, they’ll fan inflation’s flames and make Powell’s job extremely difficult, if not impossible.

As noted by The Economist, in the past year the federal government “has spent $2 trillion . . . more than it has raised in taxes after stripping out temporary factors”—despite the lowest sustained unemployment rate in 50 years.[14] Of course, the pace cannot be continued, and anything that cannot continue apace forever will have to stop at some point. However, the prospects for cutting spending, raising taxes, or finding large increases in deficit-offsetting productivity do not seem to be in the offing.

Since the president lacks a king’s authority to deliver other policy benefits, Powell can only hope Biden will also follow Canute’s lead. But Biden seems to be playing the opposing hand. Apparently believing that he can control the tides, Biden has launched a “Strikeforce on Unfair and Illegal Pricing”[15] in addition to his earlier efforts to jawbone the economic powers of the world into bringing down prices.[16]

Mr. Biden and the rising tide

Yet, while pushing his throne closer to the edge of the sea, Biden has also increased consumer prices by imposing higher tariffs on imported steel and automobiles.[17] He’s marched with the United Automobile Workers to gain increased wages for workers, which tend to push prices higher. And he’s happily canceled more than $7 billion in student debt while arguing that the burden was limiting former students’ ability to buy homes and other consumer goods.[18] That purchasing ability, if bolstered, would also tend to push prices higher.[19]

With Chair Powell watching and no doubt hoping for beneficial results, President Biden is sitting on his figurative throne, waiting for inflation’s incoming tide to obey his command. Meanwhile, his almost countless staff members are cheering him on. When will Mr. Biden pull back from the edge and take other inflation-limiting actions? Well, it’s an election year, and the president is doing everything he can to attract voters to his cause.

Bread and Circuses, American Style

Yes, primary season is fully under way, and the election year is heating up.[20] Then again, do campaigns ever really stop nowadays? There was a time when election years stood out as what Washington talking heads referred to as “crazy season”—politicians making wild promises, ordinary people egging them on, and outcomes settled in strange, unpredictable ways.[21] Some of us fretted that election season promises, if they came true, would involve someone else paying the bill. Others didn’t realize or care.

Now, with constant campaigning and candidates trying to outdo each other, we’ve developed a modern version of Ancient Rome’s bread and circuses—what emperors provided to their citizens in an effort to maintain power some 2,000 years ago. Only instead of relying on conquests and taxation to pay for these political gifts, American politicians have figured out how to stay in power by kicking a deficit-filled can down the road.

Having the dollar—the world’s reserve currency—at their disposal means our politicians can do something the Romans may have only dreamed about: they can put their bread and circuses on the country’s credit card.

Writing in 100 A.D., the Roman satirical poet Juvenal observed how emperors kept the people happy while maintaining their support. He referred to free monthly distribution of wheat for cooking and free entertainment provided across the republic. At the Colosseum, 50,000 spectators could enjoy access to sporting, combat, parades, and wild animal events, sometimes with food and drink provided.[22] It was the Roman version of a Super Bowl that occurred every week.

Juvenal worried that Romans had lost their concern for the greater good and had become unduly focused on what politicians could do for them individually. It was as if the politicians were constantly running for office.

American politicians and deficit-financed bread and circuses

Could it be that in its own way America has stumbled onto circuses and bread? During crazy season, we might hear statements from office seekers about building a 2,000-mile wall, forgiving student debt, deporting 10 million foreign-born people, bringing back manufacturing jobs, providing free college education, privatizing Social Security, eliminating the IRS, making prescription medicine free, providing free internet, ending our reliance on fossil fuels, and never raising taxes.

And, of course, like those sturdy Romans, we American voters want to believe them. Out of the promises come printing press money, increased spending, higher deficits, and growing debt. We kick the can down the road.

Public deficits have been the norm since 1957.[23] Since then, almost every year we have spent more federal dollars than were taken in. The surplus years 1998 through 2001 are an exception. Federal deficits mean more federal borrowing, of course, and that means spending a growing amount of what we have on the interest cost of the debt. In the fourth quarter of 2023, that figure—just for interest payments—rose above one trillion dollars. Only three years earlier, the cost was roughly half that much.[24]

It’s worth emphasizing what should be obvious here: paying a larger interest bill means something else cannot be purchased, unless we borrow even more money to cover the difference.

Despite these growing federal deficits, we as a nation still managed to look relatively thrifty until around 2007.[25] Before that year, the amount American citizens saved from their incomes exceeded the annual federal deficit. Combined, the people and our government enjoyed net savings, which made it possible to pay our way when consuming and supporting new investment with domestically generated funds.

Since 2007, when public and private consumption are considered together, we have consumed more than we have produced. That means people somewhere else have to consume less than they produce and ship the excess to us. Keep this in mind because protectionism—policies that limit foreign trade, which we now need more than we once did—also holds sway today. It’s simply not possible to block imports from the rest of the world without reducing the net well-being of the American people.

Secretary Yellen’s visit to China to encourage cooperation

Very much aware that US well-being depends on trade with China, Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen recently visited Beijing—a trip that was apparently successful on several fronts.[26] She engaged top Chinese officials on sensitive economic policy issues, including trade, EVs, and chips—thereby strengthening important communications links—and also impressed her hosts with her keen ability to use chopsticks while dining.[27] Perhaps the most globally experienced Biden administration cabinet member, who also possesses a winsome personality, Yellen knows how to operate in high places; she held her own with high-ranking Chinese officials.

The Yellen visit was crucial because the United States and China need each other. There are opportunities for meaningful gains from cooperation. Each year the Chinese people produce far more than they consume, which means, as mentioned earlier, that they need to sell the excess production to people elsewhere. In contrast, since the first quarter of 2023, with yawning federal deficits and a low private savings rate, we Americans have consumed more than we produce.

Our shores look like the logical destination for Chinese goods. If it were not for goods from China, our consumption habits would require the flow to come from some other foreign source. Also, with foreign ownership of US government debt now at an all-time high, China, the second-largest buyer of US bonds, held $816 billion in US bonds in December 2023.[28] Japan is the top lender; the United Kingdom is the third.

In a real sense, we borrow from China to buy their goods. If they were to stop lending, we would have to stop some of our consuming. Finally, both the United States and China have adopted the same industrial policy directives. Both countries are investing the people’s money in subsidizing the production of EVs, chips, and high-tech machinery.

While there are growing concerns about China’s next move with respect to Taiwan and China’s treatment of foreign investors’ intellectual and other property rights, the Chinese are struggling with a sputtering, high-unemployment economy. At the same time, because of a continuing low birth rate, China faces a sharply falling population and expects to lose 20 percent of its workforce by 2050.[29] Along with these problems, thanks to past errors in choosing economic goals, the nation is dealing with serious real estate bankruptcies.

By comparison, with all its challenges, the US economy looks like the fabled Yellow Brick Road. That said, our sitting and aspiring national leaders constantly speak of imposing higher tariffs on Chinese and other foreign goods. And because of the US decision to build a future on subsidized EVs and chips, our leaders seemingly tremble at the prospect of seeing hordes of Chinese-made EVs and other products arrive here to satisfy the buying habits of US citizens.

But Are We Going to Hell in a Handbasket?

If your impression of the state of the world comes mostly from the 6:00 news, you can’t be blamed for wondering if we’re all going to hell in a handbasket.[30] But if you approach the question analytically—noting what the great economist Adam Smith called the “duties of the sovereign”[31]— you’ll better understand the bad news and notice more of the good.

Writing in 1776—a significant year—Smith argued that a government’s first duty is to protect the nation from invasion; the second is to maintain civil order, keep people from harming each other, and provide justice; and the third is to engage in public works, including education. Failure in these duties tends to mean bad things happen.

For years now, we’ve seen those failures in news images of death and destruction in Ukraine, Gaza, Syria, and the Congo. Then the camera moves to our southern border and an endless stream of families from a score of countries struggling to make it to America. We hear the latest on hate crimes, mass killings, or both.

If this isn’t enough, it’s political crazy season, when presidential candidates exchange verbal slings and arrows about everything from bribery and corruption, to insurrection, to mumbling, stumbling, and stealing state secrets. There’s less discussion about the duties of the sovereign or of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Unable to get the matter off my mind, I asked a man I met at a Waffle House restaurant whether we’re going to hell in a handbasket. “No,” he replied. “We’re already there!”

Contacting hell used to require a long-distance telephone call. You don’t even have to dial an area code anymore. Apparently, the news had gotten to him.

Taking a look at data

So I turned to data on human well-being. They don’t sugarcoat the bad news, but they do offer something else.

One dataset spoke directly to the failed-state problem: the worldwide count of refugees granted asylum between 1990 and 2022.[32] Abandoning one’s home to pursue asylum abroad must reflect a failed-state problem—one such as war or domestic persecution. The count ran between 15 million and 20 million refugees per year until 2015; then it accelerated and reached a 2022 peak of 35 million. (Illegal, unprocessed migrants are not counted.) Some 52 percent of recent seekers are from Ukraine, Syria, and Afghanistan.[33] While these refugees are not heading to hell in a handbasket, I expect they are escaping one they’ve already experienced.

Since much of evening news horror involves invasions by one group against another, I next decided to look at the annual count of deaths in state-based conflicts worldwide from 1946 to 2022.[34]

There are mountains of data for the World War II years, when annual numbers of deaths for combatants hit 500,000. Then there are smaller tragic mountains for the Vietnam and Iran-versusIraq years, when the annual counts rose to around 300,000 combatant deaths. Things calmed for a few decades until 2022 and the Russia-Ukraine and Sudan wars, when the combatant death count rose back above 200,000. These counts are not just sad evidence of governments providing a national defense—they can reflect the failures that drove or invited conflicts.

What about the rest of the world?

Yet abroad is also where we find perhaps the most fundamental good news of all: the falling percentage of people in most regions and worldwide who are living in poverty, as estimated by the World Bank.[35] While the war-torn Middle East and North Africa have experienced more poverty in the past eight years, this is not the case in huge swaths of the developing world.

Moving to civil order at home, we also tend to see the bad news first. The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s hate crime data show a mostly downward trend, from more than 8,000 incidents in 2000 to 5,590 in 2014.[36] The trend then reversed, reaching an all-time high of 10,299 incidents in 2020. Crimes involving race and ethnicity are the main drivers. The US homicide rate has also generally fallen since 1990 but has ticked up lately.[37] The number of US mass killings bounced from one to five events for decades.[38] It hit 7 events in 2012, and 12 in both 2022 and 2023.

Yet there are brighter data here too. It’s hard to argue that everything is getting worse in our towns and neighborhoods. For example, the number of prisoners in federal and state prisons fell to 1,230,000 in 2022 after being as high as 1,613,000 in 2010.[39] US alcohol-related arrests have generally fallen since 1980 for large and small cities as well as suburban and rural areas.[40]

I’ve only scratched the surface. What’s clear is that failed states merit some of the evening news misery. Large regions of the world are in chaos. People are fleeing. There are also vast regions and countries where order is maintained, domestic peace prevails, and major elements of life continue to improve. Americans grappling with our own country’s failures should remain grateful that we are as yet not a failing state.

Yandle’s Reading Table

If you are looking for a book to read that you will not want to put down, you could not do better than Douglas Brunt’s 2023 The Mysterious Case of Rudolf Diesel: Genius, Power, and Deception on the Eve of World War I. [41] Far more than just a biography, indeed almost a thriller, the book provides an account of the life and times of the brilliant inventor of the diesel engine. As the title suggests, the story is also about the mystery of Diesel’s disappearance. I will provide more on this later.

Diesel was born in Paris to German-speaking Bavarian parents in 1858, and when he was quite young, his family was forced by French authorities, who were suspicious of all things German, to move on short notice to England. There the family struggled to make a living. Taken in by family and friends in Munich, young Rudolf proved to be an extraordinary scholar and went on to earn high academic records as a university engineering student.

As a young man, Diesel quickly gained employment with some of Europe’s leading machinery builders, where he was encouraged to engage in pathbreaking research. As a revolutionary inventor, he moved the world from the use of low-pressure external combustion engines, as with steam, which primarily came from burning coal, to much more efficient high-pressure internal combustion engines that could be fueled by the oil from nuts, berries, tar sands, or petroleum, thereby making it possible for any country to become energy independent.

Importantly, the switch from coal-fired steam to diesel power made it possible for oceangoing vessels to circumnavigate the globe without refueling. In a 1911 survey of ships at sea, Diesel reported that the range for diesel ships was four times greater than for those driven by steam, the crew required for operations was reduced by 75 percent, and the weight of the fuel carried on board was down by 80 percent. Incidentally, a diesel-equipped Indy 500 vehicle was able to earn a place in the contest, not because of speed but because the car did not have to stop to refuel.

Obviously a genius in the application of mathematics, physics, and thermodynamics to machinery design, Diesel also proved to be equally capable in organizing world markets and firms for the production and sale of engines that relied on his patents. As a result, Diesel became associated with beer magnate Adolphus Busch, the Krupp family, the Nobel brothers in Russia, and the Swiss Sulzer family, and he formed close acquaintances with Thomas Edison and Henry Ford. In 1898, at age 40, Diesel established a major research and development center in Augsburg, Germany, which would be his center of operations. Not too far away, Diesel, his wife Martha, and their children settled into a Munich mansion that became a familiar site for spectacular dinner parties and other gatherings. All along, Diesel was learning more about global markets as well as the ruffled feathers that occur when competing moguls, such as John D. Rockefeller, are disturbed by the threat to their aspired empires brought by technologies that could rely on nonpetroleum energy sources.

Diesel’s invention brought dramatic cost reductions and revolutionized all forms of transportation, including ships at sea, locomotives, automobiles, and, most significantly to the author’s story, submarines. As the story unfolds, the ability of a country to produce large, efficient diesel engines determined its success in the pursuit of new territories and colonies and its command of the seas. In short, Rudolf Diesel revolutionized the movement of people and goods, upset empires, and potentially empowered aspiring tyrants.

As the story unfolds, Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II realized that he might build a world-class navy capable of overwhelming Britain’s famous fleet by using powerful diesel engines. Indeed, if the diesel engine could be perfected for submarines, of which Germany was becoming a leading producer, German U-boats would make large steam-powered battleships obsolete. Diesel engine technology became part of a fundamental arms race, and Rudolf Diesel found his loyalties torn between Germany and Britain.

As Kaiser Wilhelm pushed U-boat development, threatening Britain’s command of the seas, Diesel showed allegiance to British naval interests and their aspiring sea lord, Winston Churchill. Wilhelm was not happy with the outcome. As to his mysterious disappearance, in late September 1913, Rudolf Diesel, one of the world’s most famous industrialists, was reported to have boarded a ship to make the short trip from Belgium to a final London destination. Diesel never arrived. While there were friends with him on the evening of his disappearance and possible evidence of suicide was observed, competing explanations of what may have happened continue to exist, and his death remains unresolved to this day. I will leave it for the reader to learn what the author believes happened to the amazing Rudolf Diesel. Suffice it to say, it is a fascinating story.

Notes

- Wells Fargo Economics, “U.S. Economic Outlook: April 2024,” April 11, 2024, https://wellsfargo.bluematrix.com/links2/html/31ad54d7-c27b-445e-bd1b-0411c65b7034.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Foreign-Born Workers Were a Record High 18.1 Percent of the U.S. Civilian Labor Force in 2022,” TED: The Economics Daily, June 16, 2023.

- Jeff Cox, “GDP Growth Slowed to a 1.6% Rate in the First Quarter, Well below Expectations,” CNBC, April 25, 2024.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment Situation Summary,” last updated May 3, 2024, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm.

- Bruce Yandle and Patrick McLaughlin, “The Economic Situation, March 2024” (Mercatus Policy Brief, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, March 5, 2024).

- Yandle and McLaughlin, “The Economic Situation, March 2024.”

- Jeff Sommer, “The Perils of the Fed’s Vast Bond Holdings,” New York Times, May 3, 2024.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Money Stock Measures—H.6 Release,” last updated April 23, 2024, https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h6/.

- This section is based on Bruce Yandle, “Commentary: A Remedy for Inflation’s High Tides?,” Union-Bulletin, May 3, 2024.

- The Economist, “America’s Interest Rates Are Unlikely to Fall This Year,” April 17, 2024; Seana Smith and Brad Smith, “Fed Faces a ‘Very Political Loosening Cycle’: Economist,” Yahoo!Finance, April 22, 2024.

- Jennifer Schonberger, “Powell Says Taking ‘Longer Than Expected’ for Inflation to Reach Fed’s 2% Target,” Yahoo!Finance, April 16, 2024.

- Craig Torres, “The Fed’s Forecasting Method Looks Increasingly Outdated as Bernanke Pitches an Alternative,” Bloomberg, April 21, 2024.

- Wikipedia, “King Canute and the Tide,” last edited on February 6, 2024.

- The Economist, “America’s Reckless Borrowing Is a Danger to Its Economy—and the World’s,” May 2, 2024.

- White House, “Fact Sheet: President Biden Announces New Actions to Lower Costs for Americans by Fighting Corporate Rip-Offs,” March 5, 2024.

- Rebecca Picciotto, “‘Stop the Price Gouging’: Biden Hits Corporations over High Consumer Costs,” CNBC, November 28, 2023.

- Shuting Pomerleau, “Raising Tariffs on Chinese EVs Will Contradict President Biden’s Climate Strategy,” Niskanen Center, January 18, 2024.

- Council of Economic Advisers, “The Economics of Administration Action on Student Debt” (Issue Brief, White House, April 8, 2024).

- Collin Binkley, “What to Know about Biden’s Latest Attempt at Student Loan Cancellation,” Associated Press, April 8, 2024.

- This section is based on Bruce Yandle, “Bruce Yandle: Bread and Circuses, American Style—Distraction and Debt,” Pioneer Press, February 15, 2024.

- Ezra Klein, “Contrary to Popular Belief, Politicians Often Keep Campaign Promises,” Washington Post, January 19, 2012; Ray Smock, “A Crazy Election Season,” Byrd Center Blog, April 12, 2016; Eliott C. McLaughlin, “11 of the Most Bizarre Elections in American History,” CNN, November 16, 2020.

- National Geographic Kids, “10 Facts about the Colosseum!,” accessed May 16, 2024, https://www.natgeokids.com/uk /discover/history/romans/colosseum/#!/register; Ellen Hunter, “What Events Took Place at the Colosseum in Ancient Rome?,” Ancient Rome, April 9, 2023.

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, FRED (database), “Net Federal Government Saving,” last updated March 28, 2024, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FGDEF.

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, FRED (database), “Federal Government Current Expenditures: Interest Payments,” last updated April 25, 2024, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series /A091RC1Q027SBEA.

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, FRED (database), “FRED Graph” (graph), accessed May 16, 2024, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?graph_id=1293654&rn=619.

- David Lawder, “US, China Need ‘Tough’ Conversations, Yellen Tells Chinese Premier,” Reuters, April 7, 2024.

- Lawder, “US, China Need ‘Tough’ Conversations”; Andrew Duehren, “Yellen’s Tough Message to China on Exports Tests Fragile Détente,” Wall Street Journal, April 8, 2024.

- Gertrude Chavez-Dreyfuss, “Foreign Holdings of US Treasuries Surge to All-Time High in December—Data,” Reuters, February 15, 2024.

- The Economist, “China’s Risky Reboot,” April 6, 2024.

- This section is based on Bruce Yandle, “The World’s Descent to Hell in a Handbasket Exists Mostly on the News,” The Hill, March 1, 2024.

- Adam Hayes, “Adam Smith and ‘The Wealth of Nations,’” Investopedia, April 9, 2024; Paul Mueller, “Exceptions to Liberty in Adam Smith’s Works,” Libertarianism.org, April 15, 2015.

- Macrotrends, “World Refugee Statistics 1960–2024” (dataset), accessed May 16, 2024, https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/WLD/world/refugee-statistics.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Refugee Statistics,” accessed May 16, 2024, https://www.unrefugees.org/refugee-facts/statistics/.

- Bastian Herre et al., “War and Peace,” Our World in Data, 2024, https://ourworldindata.org/war-and-peace.

- R. Andres Castaneda Aguilar et al., “April 2022 Global Poverty Update from the World Bank,” World Bank Blogs, April 8, 2022.

- Victor Dépré, “Visualizing Two Decades of Reported Hate Crimes in the U.S.,” Visual Capitalist, August 6, 2022.

- Macrotrends, “U.S. Murder/Homicide Rate 1960–2024” (dataset), accessed May 16, 2024, https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/USA/united-states/murder-homicide-rate.

- Statista Research Department, “Number of Mass Shootings in the United States between 1982 and December 2023” (dataset), Statista, April 26, 2024, https://www.statista.com/statistics/811487/number-of-mass-shootings-in-the-us/.

- Veera Korhonen, “Number of Prisoners under Jurisdiction of Federal or State Correctional Authorities from 1990 to 2022” (dataset), Statista, December 12, 2023, https://www.statista.com/statistics/203718/number-of-prisoners-in-the-us/.

- Connor Harris and Charles Fain Lehman, “Fixing Drinking Problems: Evidence and Strategies for Alcohol Control as Crime Control” (Report, Manhattan Institute, New York, May 25, 2022).

- Douglas Brunt, The Mysterious Case of Rudolf Diesel: Genius, Power, and Deception on the Eve of World War I (New York: Atria Books, 2023).