With the first few months of 2023 under our belts, now is a good time to look back on early 2022 and revisit expectations that have since been dashed by economic events—and see if there are lessons to be learned for 2023 and beyond. But before doing that, let’s take a quick look at some expectations for this year. A quick review of the mood at the recent World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, helps to set the stage.

In January, a lot of smart people gathered for the annual World Economic Forum. They brought with them a bevy of reports on the economic outlook. According to surveys released at Davos, the outlook was “less than cheery.” The global consultancy PwC released a state-of-the-world survey of more than 4,000 CEOs from 105 countries at Davos. Almost three-quarters (73 percent) of those business leaders expected global GDP growth to fall in the year ahead. Perhaps more challenging than the economic outlook, some 40 percent of the CEOs surveyed doubted that their firms would be viable in 10 years if they did not transform their way of doing business.

As Elvis put it, “There’s a whole lotta shakin’ goin’ on.”

Inflation, macroeconomic volatility, and geopolitical conflict were the top three concerns highlighted in the PwC survey. Indeed, the invasion of Ukraine has induced a realignment of trade between the West and Russia, China, and India unlike anything seen perhaps since the Cold War from 1945 to 1990. The realignment is accompanied by continuing national efforts to cushion the combined effects of the COVID19 pandemic and war-induced rising food and energy prices and to steer new capital investment in ways that reduce dependencies on countries now deemed to be less friendly to the West. Along with these efforts come losses in gains from trade that previously encouraged growth of global markets.

What Forecasters Are Saying about the US Outlook

With the books not yet closed for 2022 real GDP growth, there is agreement among US forecasters that 2023 will bring slower growth. In late February, the US Department of Commerce reported the second estimate for 2022’s fourth quarter real GDP annual growth rate as 2.7 percent, somewhat weaker than the third quarter’s 3.2 percent. Solid consumer spending on services was a main driver, along with heavy industrial inventory increases in coal and petroleum products. Hit hard by high interest rates, housing activity continues to weaken.

The report offered some comfort for those understandably worried about inflation. The fourth quarter GDP price index increased at an annual rate of 3.2 percent versus the third quarter’s 4.8 percent and the second quarter’s 7.3 percent. But the economy weakened considerably in December. In response to the Federal Reserve’s effort to slow the economy, retail sales and industrial production fell in December, but January retail sales, driven by spending at restaurants and other services, rose sharply. While these key measures of economic activity were sending mixed signals January employment data pointed strongly toward the North Star. Surprisingly, given the Fed’s interest rate run-up, 517,000 workers were added to US payrolls in January; the average for 2022 was 401,000. Needless to say, the world economy—as well as that of the United States—is being rewired and therefore is difficult to understand using the learning of the past.

I should point out that the happier inflation news does not surprise those who keep an eye on money supply growth, which, after all, is the definition of inflation. The rate of growth of the broad measure of money in the economy, M2 (which includes cash, deposits, and CDs, which also soared in 2021 when stimulus dollars flooded the economy), is now showing negative growth. As the money supply inflates and deflates, so too do indicators of inflation.

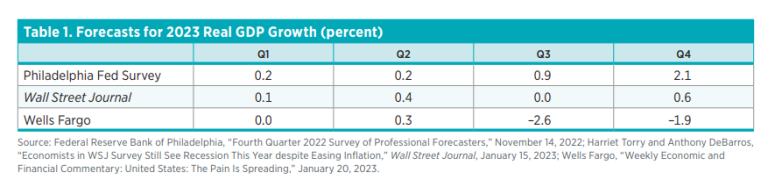

Expectations for the current year’s GDP growth are considerably diminished. As indicated in table 1, the panel of economists of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia sees hardly any growth in this year’s first nine months, but does see acceleration in the final quarter. The Wall Street Journal panel agrees with the Philadelphia Fed panel, but with no final quarter acceleration, and Wells Fargo looks for practically zero growth in the first half and seriously negative growth in the last six months of 2023. Of the three, I am more inclined to agree with Wells Fargo, but with a milder slowdown in the last half of the year. My inclination is based on what is happening to the growth of the money supply and its effects 12 months out. (More on this later.)

How This Report Is Organized

The remaining parts of the report are organized as follows. The next section takes the reader back to early 2022 and considers what was expected versus what happened. The section reviews some 2022 forecasts and then focuses on the later economic train wreck that, in effect, changed everything. The following section looks closely at the effects of massive interventions in the economy that accompanied the pandemic and how those actions distorted the signals that economic agents rely on when deciding whether to expand or cut back on businesses and investment.

In addition, that section describes how a ”normal” economy may be thought of as an information system, but it also discusses how a system that is heavily affected by government intervention can bring miscalculations, unsustainable expansions, and large layoffs. The section also discusses large layoffs in the tech sector and examines interventions in the US economy that include payments to banks for reserves held by the Fed. The report then brings a discussion on regulation by the director of the Mercatus Center’s Policy Analytics project, Patrick McLaughlin, who gives a report card on the large growth of US regulatory activities that includes a comparison with other countries. The report ends with book reviews from Yandle’s reading table.

THE VIEW FROM A YEAR AGO

Last January, no one could have predicted the economic train wreck that was to come. Some of us recognized that a train loaded with stimulusinduced consumer purchasing waiting to fuel inflation was rolling full steam ahead. But the second train—Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which destroyed lives, homes, and cities and forced a dramatic rewiring of global energy and grain markets—had not left the station.

A year ago, Americans, finally unleashed and unmasked from COVID restrictions, had reasons for optimism. Real GDP growth for 2021 was pacing at a rip-roaring 5.7 percent, the January unemployment rate was just 4.0 percent, and more than 11 million job openings were beckoning the 6.5 million unemployed to come to work. Consumers had stimulus money jingling in their pockets.

This Time Last Year

This time last year, it was hard to find a new car ( just as it is now), housing was in short supply, and it wasn’t easy to locate builders to help with home improvements. The result? Our money did not get spent quickly. There was a lot of what would later be called “excess savings.”

A few economists of note who were focused on the astounding growth in the money supply— all those stimulus checks—and on the historic relationship between that growth and inflation sounded the alarm. For example, Johns Hopkins University economist Steve Hanke and Florida State University economist James Gwartney believed high inflation was inevitable. But the “it’s only transitory” contingent, progressives, and new monetary theory thinkers denied the link, and the more politically appealing position held sway.

Used car prices had already headed skyward along with the prices of practically everything else. In November 2021, the Consumer Price Index had risen 6.8 percent year-over-year, the largest increase in three decades; by June 2022, it would hit 9.0 percent.

But the Fed had said not to worry, pointing to lingering supply chain problems. Instead of decisively pulling the brake lever ahead of the curve, the Fed’s January 2022 interest rate decision called for the controlled overnight interest rate to range from zero to 0.25 percent. But in March 2022, the Fed reversed its stance and hit the brakes. The targeted overnight rate was raised to 0.25 to 0.50 percent. Thus began a series of increases that has continued to this day.

Oh, how things changed. The train loaded with purchasing power and the train filled with war supply reductions converged. The target for the Fed-controlled rate is now 4.5 to 4.75 percent.

As late as March 2022, respected analysts at the International Monetary Fund, Wells Fargo, and the Wall Street Journal were optimistically calling for 2022’s real GDP growth to exceed 3.0 percent and for 2023 to peg 2.4 percent or better. As indicated earlier, some of those same forecasters today expect less than 1.0 percent growth in 2023. But we should be advised: there’s still a lotta of shakin’ goin’ on.

Two Lessons Learned

This story has many moving parts, and a few lessons we might learn. Let’s consider two of them.

First, the economic ramifications of the war, while never ignored, were underestimated. The disruption to energy and grain markets sent chaotic tidal waves across the global economy and caused huge populations of people to face starvation and major US trading partners to face recessions. Meanwhile, US stimulus and record-setting domestic spending programs continued apace.

Second, the relationship between money and the economy still matters. Far too little attention was given to the inflating power that trillions of government-created dollars would have when inflation became embedded in a government-stimulated economy.

These are tough lessons, and they lead me to hope that we’ll do better in the years ahead. The Chinese zodiac calendar marks 2023 as the year of the rabbit, a time to celebrate longevity, peace, prosperity, and hope for the future. Surely these happy prospects could not come at a better time. But what about job growth? Will unemployment surge? And will we see Goldilocks, that evasive but hoped for soft landing, again?

Jobs, the Economy, and Goldilocks

The Department of Labor’s December 2022 jobs report brought good news on the 223,000 nationally added jobs, a slightly lower unemployment rate, and best of all for inflation fighters (although maybe not for workers who hope to get ahead of inflation), a 4.6 percent gain in wages, the smallest since mid-2021. In reaction to the report, the S&P 500 index headed skyward. Indeed, the response was so positive that some suggested Goldilocks had risen from the dead, that things might turn out just right, and that the US economy might avoid a 2023 recession after all. As mentioned earlier, on the one hand, the unusually strong January employment numbers can be thought of as confirming this possibility; but, on the other hand, they may force the Fed to hit the brakes harder.

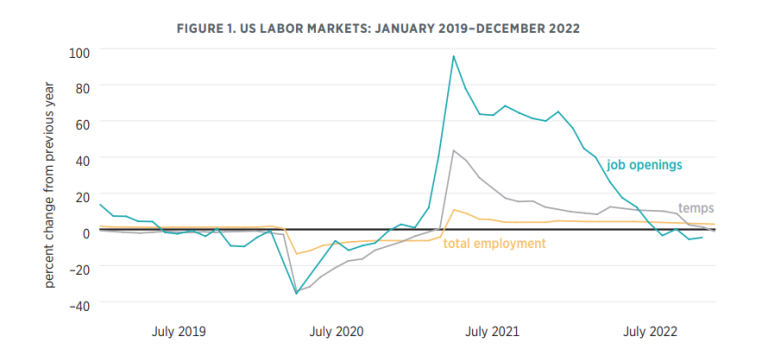

When the Fed figuratively hits the brakes, credit tightens, lending heads south, and growth in bank deposits slows accordingly. Consumers cut back on spending, and employers stop hiring as many workers. Less money is chasing the same goods, and inflation declines. How this relates to employment is shown in figure 1, in the line showing growth in job openings, an indicator that US businesses are looking for help. The line accelerates in 2021, when large amounts of stimulus money were flowing to consumers and the Fed was easing interest rates. Later growth is slower in 2022 when the Fed starts hitting the brakes.

But real action comes when firms actually hire people and employment responds. This is seen in the total employment line of figure 1. Employment growth jumps in June 2021, then falls and grows at an almost constant rate from that point forward, giving a flat growth curve that looks very much like growth in 2019 and 2020. The two lines together—job openings and total employment—tell us that US employers are now taking down their job opening signs, but they are holding on to their employees. As the signs come down, we may hear the three recessionary bears growling a warning in the distance. But as employment holds steady, Goldilocks may still be feeling just right.

Firms can take another action when dealing with a stop-and-go economy. Employers can add and discharge temporary workers. This is illustrated in the “temps” line in figure 1. Note the explosive growth that occurred around June 2021 and the sharp decline in growth that has occurred since June 2022. Also note that in the current period, growth in the number of temporary hires is falling.

So far, employment growth is holding steady, employers are hedging their bets by laying off temporary employees, and help wanted signs are coming down. The economy is surely slowing, but it is possible that employment growth will not turn negative, unless the Fed persists with heavy halfa-point increases in interest rates over the next few months.

Yes, Goldilocks may still have a chance, but it is a slim one. Indeed, the recent news on large high-tech and other layoffs leaves many analysts wondering about the severity of the labor market adjustments.

LAYOFFS, MISCALCULATIONS, AND MONEY TO BANKS

News in January that more than 40,000 employees in the tech industry were receiving pink slips and that additional large layoffs were occurring in financial services and retailing is a sad reminder that reducing inflation comes at a high cost. Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Salesforce, Goldman Sachs, BlackRock, and McDonald’s find themselves figuratively, if not literally, removing “help wanted” signs from their premises and reversing their recent high-paced hiring.

Indeed, following the surge in overall demand that was generated by federal stimulus spending starting in 2019, tech sector employment surged, with 260,000 new jobs added in 2022 alone. This gives a bit of perspective to the 40,000 job cuts, but every job loss is still a painful experience for those affected. In addition to large cutbacks in the better-known tech firms, we find that Twitter, Lyft, Redfin, Snap, Stripe, and Robinhood are significantly cutting their payrolls. Are Fed-induced higher interest rates the cause? COVID subsidies and government checks in bank accounts? Inflation? Or maybe just management miscalculation? Yes! It is all the above. The roller-coaster economy that results from these actions can generate disasters for countless families and individual workers.

We as a nation have no choice but to adjust to global events that seriously disturb what might be called normal life. But some policymakers have a tendency to quickly blame free markets run amok for high prices and related struggles that have led to the Fed’s anti-inflation actions. Forgotten, it seems, is that markets at their very foundation are sophisticated information systems. By way of countless regulatory interventions, we’ve chosen to distort that information rather than use it.

Prices or interest rates grounded in the dayto-day buying, selling, lending, and borrowing decisions of people across the world are signals that guide business owners and operators when they are deciding how many people to hire or lay off, how much to produce, and where goods and services are most needed. As pointed out in 1945 by Nobel laureate F. A. Hayek in “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” bad market signals, which can result from government intervention in markets, can lead to social calamities.

Much Has Been Said of Miscalculations In explaining what’s going on, Stripe CEO Patrick Collison said, “We were much too optimistic about the internet economy’s near-term growth,” and that the company had “underestimated both the likelihood and impact of a broader slowdown.” Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg apologized to his laid-off workers and said, “The macroeconomic downturn, increased competition, and ads signal loss have caused our revenue to be much lower than expected. I got this wrong.”

But there’s more. Chiming in from the more secure setting of the US Senate and expressing concern over the hardships, 11 Senate Democrats called on Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell to provide estimates of the number to be laid off and to explain how the layoffs might be avoided: “We are deeply concerned that your interest rate hikes risk slowing the economy to a crawl while failing to slow rising prices that continue to harm families.”

The letter, given its purpose, did not ask about the years of Fed-induced low interest rates that may have encouraged a hot-house economy. Nor did the senators mention the trillions of printing press dollars that had been sent to citizens nationwide to soften the blow of COVID shutdowns. Is it any wonder that business and government decision makers are now having trouble making the right decisions?

We know that low-cost money encourages investment in new homes, factories, and advanced research and education. And we know that income subsidies lead to higher levels of consumption. We also know that all of this can lead to higher inflation. What we have difficulty knowing is how much of the resulting economy is real, in some sense of the word, and how much of it is artificial.

It’s when the hothouse door is opened and the heat is turned down that we begin to discover the answer. And only then do we begin to learn how much it will hurt and how long it will take to recover a reality-based economic footing—one that leads to fewer “sorry, but you are fired” messages.

Should the Fed Be Sending Billions to Banks?

In all the hue and cry about the Fed’s efforts to raise interest rates to quench inflationary flames, not much has been said about how these higher rates are raising the level of payments to banks for reserves held by the Fed—to the tune of more than $100 billion this year—and at a time when the Fed itself is running a monthly deficit, the first since 1915, and is unable to send one thin dime to US taxpayers.

But where does the Fed get all that money? What happens when the money spigot closes? And does it all make sense?

Fed revenues come from interest and capital gains earned on vast holdings of government bonds as well as for services rendered to Fed member banks. Each year, the Fed normally makes enough money to send a large payment to the US Treasury, and this provides a welcome benefit to US taxpayers. In 2022, the Fed sent a net $107 billion to the US Treasury and in 2021 it sent $86 billion. This year, the Fed expects to operate with a loss.

As part of tightening the monetary screw, the Fed is also selling off interest-bearing securities and not replacing them. Simply put, Fed revenue is down and Fed costs are up, in part because of accelerating interest payments to banks. We taxpayers are in for leaner times.

A quick look at some numbers will shed light on the bank part of the story. At the end of October, bank reserves held at the Federal Reserve totaled a bit more than $3.05 trillion.36 In late January, the interest rate paid on reserves was 4.4 percent. This rate was set on December 15 when the Fed raised rates for everyone else. (When the Fed raises rates at its regular meetings, the bank rate rises automatically.)

At 4.4 percent (and likely rising), and with $3 trillion in reserve, this yields $132 billion annually headed to banks’ bottom lines. Just a year ago, the Fed was paying 0.15 percent on bank reserves, which for $3.8 trillion in 2021 reserves caused banks to get a pale $5.7 billion.

Why are big checks going to banks in the first place? An important Texas A&M Free Enterprise Center policy study authored by Tom Saving provides important background on this and more. It all began in 2008 when the US financial economy was going through the ringer. At the time, the normally independent Fed was deeply engaged with the US Treasury, and together they were working with Congress to shore up beleaguered banks—and strong banks, too. In the midst of the Great Recession, Congress legislated, and the Fed followed the orders.

Interest paid on reserves started in late 2008. At the time, total bank reserves with the Fed stood at a lowly $184 billion. Since then, the level of reserves has become swollen as the Fed bought bonds from the public, which put a lot of money in bank accounts and in Fed bank reserves. Meanwhile, US banks are doing okay, and with this year’s interest payment, they will be doing a lot better. Of course, financial markets have adjusted to all this. Most likely, bank stocks are less risky than they once were, but clearly times have changed.

Writing about the Fed’s payment of interest to banks in 2016, former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke and Brookings Institution economist Donald Kohn offered an explanation and a justification for the interest payment system. At the time of their writing, the interest rate paid on reserves was still quite small—0.25 percent—as were the total payments. Bernanke and Kohn made the point that when interest rates rose significantly, the Fed would have to deal with a public perception problem. The Fed would have to confront the following question: Why are taxpayers losing revenues from the Fed so that big banks, some of which are foreign owned, receive billions in Fed payments?

It has been 14 years since it all started. Perhaps it is time to end a program designed in part to buttress a recession-stressed banking system. Yes, it may be time for Congress to reexamine the entire matter and consider paring down the payment rate and eventually closing the spigot that now feeds billions of dollars from taxpayers to banks that hold reserves with the Fed.

PERSPECTIVES ON REGULATION

Patrick McLaughlin | Director, Policy Analytics Project, Mercatus Center at George Mason University

How can we better understand the volume of federal regulations that exists in the United States and what it means to you, to me, to businesses large and small, and to nonprofits? The first step is to determine the metric to use for volume. The next step is to determine what this metric means for our economy when compared to the rest of the world.

One approach is to use the number of pages in the US Code of Federal Regulations as a measure of volume. Another approach, the one we use, is to count regulatory restrictions on the books—words and phrases such as “shall,” “must,” and “may not” that prohibit actions or prohibit obligations to take some action.

What does it mean to have more than 1 million regulatory restrictions in the Code of Federal Regulations?

One path to better understanding this number is to see how that quantified volume of regulations affects different aspects of the economy. This approach has been used in hundreds of empirical studies of the effects of regulations on growth, employment, poverty rates, and many, many other economic outcomes of interest.

Another approach is to compare the volume of federal regulations in the United States with the volume in other jurisdictions. For example, we can compare the number of pages in the US Code of Federal Regulations with the number of pages in the equivalent regulatory codes of other countries. Although we don’t necessarily know what the “correct” volume of regulation should be for a given country, it might be illuminating to see which countries have the greatest or the least number of regulatory restrictions on the books. By comparing the breadth and depth of regulations in different countries, for example, we might gain some perspective on the regulatory environment here in the United States.

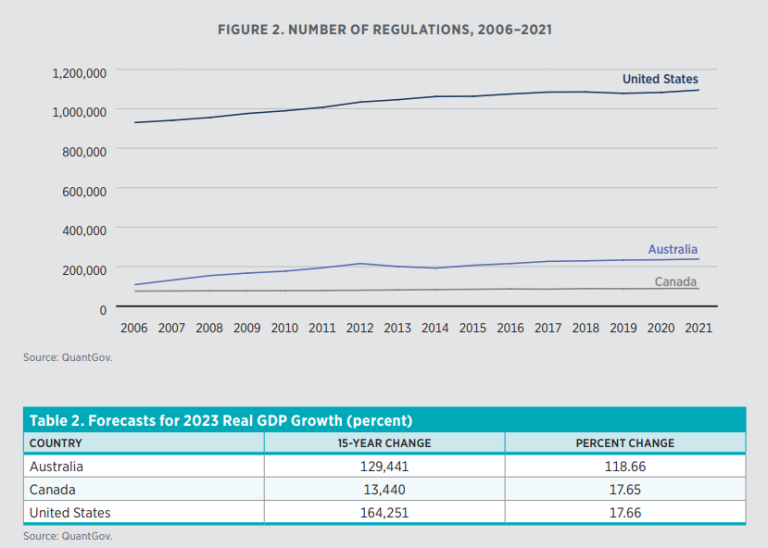

As of the end of 2021 (our last year of data so far), the United States had 1,094,447 regulatory restrictions on the books. In contrast, in 2021, Australia had 238,528 regulatory restrictions on the books at the federal level, and Canada had 89,569 restrictions at the federal level (see figure 2).

In addition to making comparisons between jurisdictions, we can also compare the volume of regulations over time. We can ask questions: How has the number of regulations changed over the years? Are there certain periods in which the number of regulations increased or decreased significantly? Is the current volume of regulations higher or lower than in the past?

Australia, Canada, and the United States have seen regulations grow for the years that we have data, but Canada stands out for having the least growth—both in absolute terms and in percentage terms. Table 2 gives the number of restrictions added during the 15-year period for each of the countries, and the percent change during the 15-year period.

Another thing that stands out about these data is simply how much more regulation the United States has compared with Australia and Canada. There are many possible explanations as to why. For one, both Australia and Canada use a Westminster-style parliamentary system of government, whereas the United States has a presidential system with a strong executive branch.

Another explanation for the differences could be “regulatory hygiene.” Canada, in particular, has been relatively proactive in cleaning up old regulations that it deems no longer necessary or even counterproductive. It’s a different approach to regulation compared with what the United States does, and it shows in the data. The approach amounts to simply not assuming that all regulations that are created should remain on the books in perpetuity and instead creating a process for reviewing the old ones on a regular basis and trimming those that are unnecessary. Which, of course, makes sense. Besides some governments, are there any organizations that don’t periodically review their own rules and processes?

Sadly, the United States remains on a different course altogether. Even though the United States’ percent change is almost identical to Canada’s during the 15-year period, the number of restrictions added to its books is more than an order of magnitude greater than the number added to Canada’s.

The United States has 12.2 times more restrictions than Canada.

Are US residents, with 12.2 times more restrictions than Canada, also 12.2 times safer? Is the environment 12.2 times cleaner and better protected? In short, are the benefits of leaving so many regulations on the books worth the costs, which I wrote about in this same space in last quarter’s report?

Canada might be showing us the answer. No one believes that Canada’s safety, environment, or other valuable goods that regulations protect are any worse off than the United States’. But plenty of people believe that the United States has too much red tape. It is up to policymakers in Washington to begin to adopt better regulatory hygiene and to clean up the old regulations that do nothing more than create friction in the engine of our great economy

YANDLE’S READING TABLE

Erskine College historian John Harris’s The Last Slave Ships (Yale University Press) is a fascinating examination of the final decades of US-based slave trading. Based on his Johns Hopkins University dissertation, the book, as expected, is highly documented and reflective of many hours spent reading documents, histories, and trading records. As Harris reports, despite the 1808 US ban on the slave trade, England’s strong and expanding efforts to police and end slave trade traffic at sea, and the fact that by 1836 every nation that had previously been involved had outlawed the trade, the illegal slave trade business flourished under US-flagged ships and was centered in Manhattan, New York, from the 1850s until the Civil War.

This “illegal” industry could flourish because US-flagged ships were used, obtaining flag approval was easy, and England, the chief antislavery trade enforcer at the time, deferred to vessels flying the Stars and Stripes. But let’s be clear. No slaves were being transported to or traded in New York. New York was the location of the offices of sophisticated traders who were involved in ship construction, outfitting, and seafaring operations. They dealt with African slave providers, primarily in the Belgian colony of Angola; transported shiploads of slaves, mostly to Cuba; and saw that the cargo was safely unloaded and delivered to Cuban sugar producers.

The traders, who generally were not US citizens, were respected members of New York’s society, and their businesses were highly profitable. The operators of the last slave trade flourished right up to the time of the Civil War, when all forms of US-based commercial slaving activity were finally halted.

Harris’s book is replete with the details of how the slave trade business was organized. Generally speaking, two groups of investors were involved. The first group invested in ships and bore the risk associated with confiscation that might result from encounters with British slave trade opposition. The second group invested in the slave cargo. These investors bore the risk of deaths at sea—on average, about 20 percent of the slave cargo died at sea—and the risk of fluctuations in market prices. We learn from Harris that the business of slave ship construction flourished in Baltimore, and that after 1852, 91 percent of 474 slaving shipments took place in 59 Baltimore-built ships, but that the typical vessel’s distinguishing decks that housed the slave cargo were completed at sea, long after leaving US waters. Often, slave ships on the way to Africa carried common commodities like flour from the United States, to be unloaded in Spain or elsewhere on the way to Angola.

The author’s description of the horrible conditions experienced by more than 100 slaves packed spoon-like on a ship deck obviously cannot match what it must have been like to be in that number. The trips from Africa to Cuba took 50 to 60 days. Large quantities of food had to be prepared along the way, and drinking water had to be supplied. After all, the investors who owned the slaves during transit wanted to get a return on their money. Often, slaves were from different tribes and, as we know, could not communicate with their fellow victims or their captors. In any case, Harris’s treatment of these and other details helps one to understand the relative magnitude of the slave trade business both for the trader and the shippers and for the on-the-ground Africa-based enterprises that formed one of the larger industries in slave-gathering countries.

Harris’s book is data rich and provides details on the business side of slavery that help explain the enterprise side of the story. In a way, just as Prohibition paved the way for an illegal but profitable business that came much later in US history, the weak enforcement of US slave trade laws, bribery of officials, and high demand provided money-making opportunities for those who ventured into the industry. Sadly, as we all know, this story is about trade in, and violence imposed on, human beings, and the death and destruction that accompanied that trade.

Harris’s book is a worthwhile read.

“Better late than never!” The old saw came immediately to mind as I began reading Pete Leeson’s marvelously entertaining and informative 2009 book, The Invisible Hook (Princeton University Press). My Clemson book club had selected the book, and I knew we were on to something different when on the dedication page, the author had posed a question to his girlfriend: “Ania, I love you; will you marry me?” And, I knew about Pete’s breakthrough work on piracy economics. But let me pause right here and urge you to get a copy of Pete’s book and read it! You will be glad you did, especially if you are interested in seeing economics in motion.

I am so enthusiastic about The Invisible Hook because it applies Adam Smith’s invisible hand concepts to 18th-century piracy with a vengeance. The book is about the industrial organization of the pirate industry, the economic organization of individual pirate vessels, and the remarkable extremes to which pirate captains went to avoid unnecessary costs, to increase profits, and to encourage crew productivity. Indeed, I think it would be interesting and worth the effort to use the book as a backbone for an undergraduate industrial organization (IO) course.

But the book is about more than IO. It also contains lessons in public choice economics and how unrestrained efforts to maximize profits can lead members of an industry to do some surprising things, such as to write ship constitutions that give crew members the right to vote on who will captain the ship; to own slaves while employing Black crew members, as well as people from other nationality groups, to work side by side with equal pay and political voice; and to invest in piracy brand-name capital so there is no doubt in potential victims’ minds that when they encounter pirates they should surrender as quickly as possible and cooperate with the apparently wild and evil marauders at the first opportunity.

Leeson masterfully weaves market-based economics into his data-rich tales of piracy, which reflects a dedicated effort on his part to find and read histories, trial records, and newspaper accounts of pirates and their activities. The book’s eight chapters portray a highly profitable and extremely risky industry, one in which individuals with high discount rates and a preference for extreme risk taking brought home lots of loot, perhaps along with peg legs and other mutilations. I found the chapter on the Jolly Roger, the flag raised when a pirate vessel was signaling its presence to a victim, to be one of my favorites. As Leeson tells the story, most pirate ships were larger and faster, were better equipped with guns, and carried a much larger crew than the merchant ships that were their victims.

As it came into view of a potential victim, with guns disguised and the crew hidden below decks, the pirate ship would lower its false national flag and raise the large, black-and-white Jolly Roger, which conveyed certain and quick death for all who might resist the pending attack. The vessels that resisted were sacked and often burned, and every crew member was murdered mercilessly by cruel and torturous means. In contrast, the vessels whose captains and crews cooperated were salvaged, and sometimes these vessels were given back to the captain to sail again and many of the cooperating crew were offered high-paying pirate ship employment. There was no torture or wholesale murder for cooperators. The Jolly Roger strategy minimized the cost of attacking and the loss of valuable crew members, and it established a winning brand (perhaps a brand hated universally by pirate victims—but equally understood).

Although piracy on the high seas flourished for only a few decades, the industry, with its hundreds of pirate vessels, countless attacks, and many encounters with “law enforcement,” left a rich historical record that Leeson researched to build his book about the invisible hook. I wish I had read it sooner.

Citations and endnotes are not included in the web version of this product. For complete citations and endnotes, please refer to the downloadable PDF at the top of the webpage.