- | Housing Housing

- | Policy Briefs Policy Briefs

- |

Getting Corporate Money Out of Single-Family Homes Won’t Help the Housing Affordability Crisis

Since the Great Recession, a new sector has emerged in US housing markets: Wall Street firms are buying large portfolios of single-family homes to manage as rentals. As housing costs across the country continue to soar—for both renters and buyers—these new corporate landlords have become an easy scapegoat. In response, policymakers at the local,[1] state,[2] and federal[3] levels are seeking to limit large firms’ ability to buy existing or new homes to manage as rental properties.[4]

But before they do, policymakers must ask why this new sector has developed. The answer to that question should give them pause: Regulations at all levels of government have limited the production of housing of every other form. Making this new and growing form of housing illegal as well would only continue the trend of legislating homelessness.

Owner-Occupiers Drive Up Prices; Landlords Do Not

Traditionally, there have been three types of owners in American housing:

- Corporations and other institutional landlords. The dense concentration of apartments, mobile homes, or urban multi-unit buildings within a single property makes them easier to manage, and these forms of housing have been favorites among corporate landlords.

- Small-scale investors. The ownership of single-family rental homes has traditionally been very decentralized. Local investors tend to buy older, depreciated properties, which can be purchased cheaply relative to their rental value.

- Homeowners. About six out of seven single-family homes are owner occupied. On the other hand, only about one out of seven multi-family units are owner occupied.

Fee simple ownership of a lot with a home lends itself to owner-occupier tenancy. Communal structures lend themselves to landlord management. There has historically been little overlap. Where there is overlap of landlord management and single-family units, it has always been dominated by small-scale landlords.

Frequently forgotten in the aftermath of the Great Recession is the following implication: Individuals naturally outbid investors for single-family homes. Under the range of mortgage lending norms that were in force from World War II until 2008, there was never a significant corporate presence in single-family homes. That is because, when they can get mortgages, prospective owner-occupiers are willing to pay more for single-family homes than corporate landlords are. Large institutions don’t have inherent market power over families with access to mortgages.

Furthermore, in every metropolitan area, homes in neighborhoods with higher rates of homeownership sell at higher price-to-rent ratios than do homes in neighborhoods with lower rates of homeownership.[5] Owner-occupiers drive up prices; landlords do not. Homeowners who can get mortgage funding have always and will always be willing to pay more for homes than landlords will.

The issue to be addressed: Why are corporations now buying single-family homes? Such behavior is an anomaly, not a natural, inevitable result of corporate power. What then is the explanation?

Lending to Borrowers with Lower Credit Scores Has Decreased

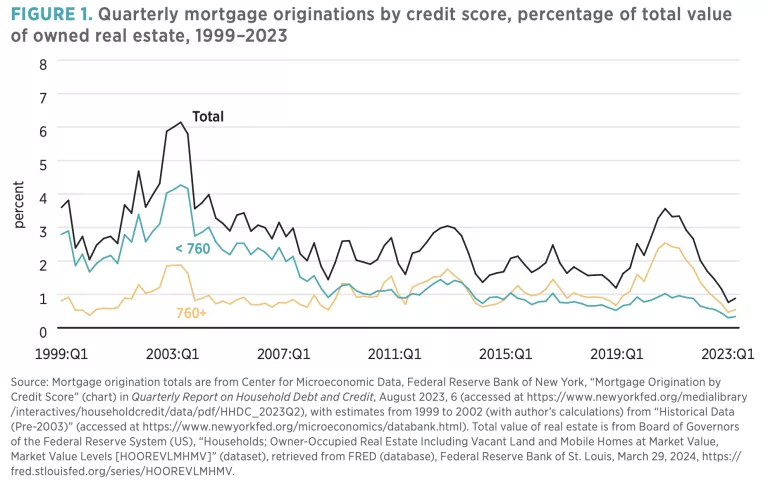

Figure 1 shows the quarterly amount of mortgage originations (new mortgages) as a percentage of the total value of owner-occupied housing.(When interest rates decline, many households refinance their mortgages. That explains the bumps in 2003, 2012, and 2019. Note that the 2003 bump predated the subprime private securitization boom, which dominated new mortgage activity from 2004 to early 2007.) Except during the refinance booms, borrowers with credit scores higher than 760 regularly borrowed capital equal to about 1 percent of owner-occupied US housing stock each quarter, both before and after the Great Recession.

Before the Great Recession, borrowers with credit scores below 760 regularly borrowed capital equal to between 2 and 3 percent of the value of owner-occupied US housing stock. That percentage range, as well as the proportion of mortgages originated to borrowers with lower credit scores, didn’t rise appreciably during the subprime boom period from 2004 to 2007.

Then, between 2007 and 2009, the proportion of new mortgages going to borrowers with scores below 760 dropped by more than half and remains that low today. (The average credit score among all borrowers tends to be a bit above 700 points.)

The Crackdown on Mortgage Lending Reached Prime Borrowers with a History of Mortgage Access

This change wasn’t a reversal of the boom era subprime lending excesses. The same pattern showed up at Fannie Mae (Federal National Mortgage Association).

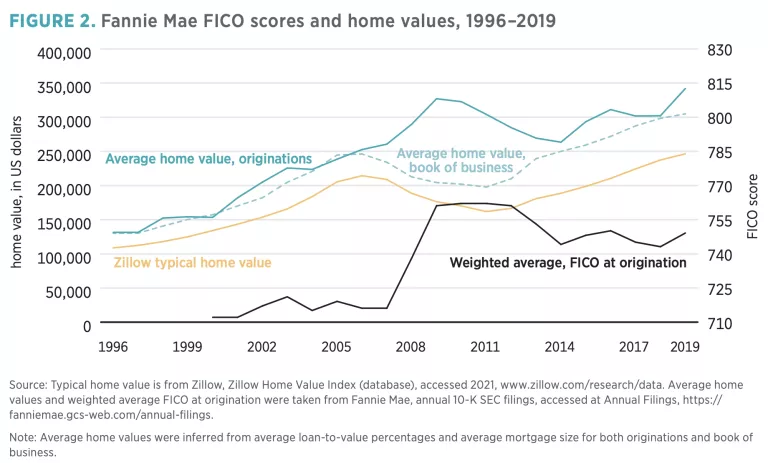

As figure 2 shows, from 2000 through 2007, the average credit score on Fannie Mae mortgages barely changed. Figure 2 also compares Fannie Mae’s estimate of the value of homes being funded by new mortgages and the value of homes in Fannie Mae’s book of business (homes with mortgages that had been originated in earlier years). Home prices had risen, but the homes associated with old mortgages had similar values to the homes associated with new mortgages. In other words, even though home prices were rising, the mortgages were going to the same types of borrowers in the same types of homes in 2007 that they had been going to for years.

By 2009, the value of homes across the country, including those with Fannie Mae mortgages, had fallen significantly. But in 2009, the average credit score on new Fannie Mae mortgages was about 40 points higher than it had been previously. And, strikingly, the average value of those new homes skyrocketed to well over $300,000—about 60 percent higher than the homes with mortgages from earlier years.

The profile of borrowers served by conventional lenders changed greatly after 2008. Those with credit scores under 760 were much less likely to qualify for mortgages, so the homes those borrowers were likely to live in had fewer potential buyers.

Small-scale landlords own only about 15 percent of single-family homes. There was no existing market of buyers capable of filling the gap that was left when those buyers with lower incomes and credit scores disappeared.

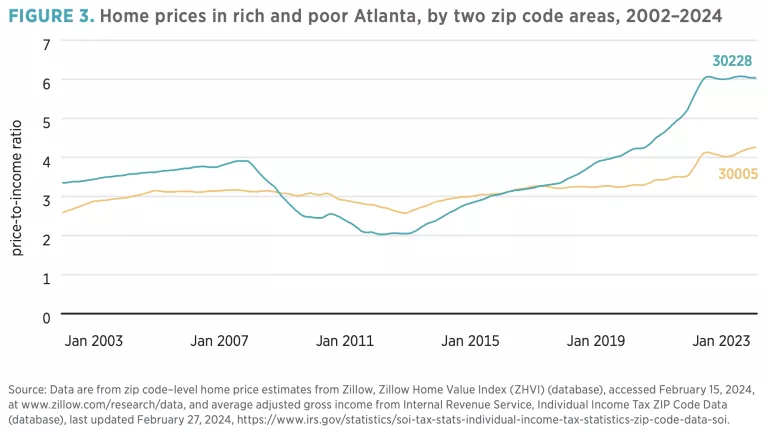

In Neighborhoods Where Mortgage Access Dried Up, Home Prices Collapsed

Figure 3 compares the prices of homes in two zip codes in the Atlanta, Georgia, area. This pattern is common to many cities across the country. Before the Great Recession, prices and construction activity had been moderate in most places, and price spikes were limited to certain cities. In most cities, as they were in Atlanta, prices and construction were moderate.[6] Before the Great Recession, the prices of homes across Atlanta generally scaled with incomes. In the 30228 zip code, which today reports average incomes of about $50,000, homes sold for just under four times the average income. In the 30005 zip code, which today reports average incomes of about $160,000, homes sold for about three times the average income.

Those levels were historically pretty normal for a city with adequate housing. At those prices, builders started a moderate number of new homes each year that accommodated Atlanta’s growth. Families with a wide range of incomes could find affordable homes somewhere in the metro area.

Where incomes were lower and homebuyers depended more on access to credit, home prices declined. So, in zip code 30228, where home prices had never been especially high, they fell by half.

Investors Bought Homes Because They Were Cheap

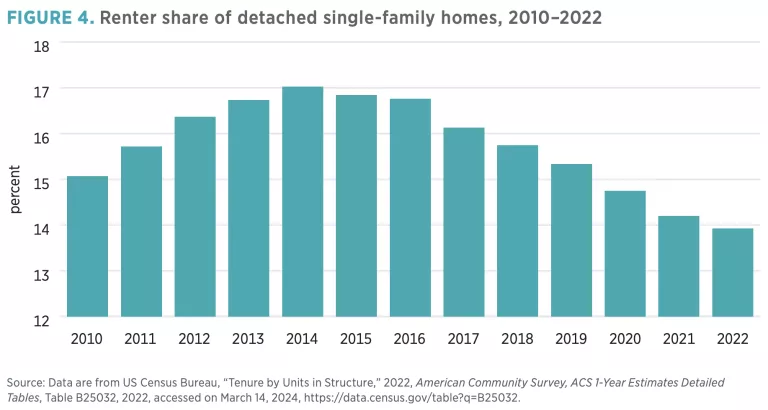

In the years after the Great Recession, the share of single-family homes that were rented increased. Figure 4 shows that the renter share of single-family homes was 15 percent in 2010 and rose to 17 percent in 2014. Institutional owners were the only sector with the scale to purchase the number of homes that households could no longer buy under the new lending standards. Prices bottomed out when institutional buyers entered the market. Eventually, prices started to rise back to normal levels, but for most of that time, the portion of single-family homes that were owner occupied was increasing, and the portion that were rentals was decreasing, as shown in figure 4.[7]

Prices did recover from those lows after investors entered the market, but institutional buyers weren’t pricing out homeowners. Homeowners were unable to buy homes that were priced at historic lows.

Builders Can’t Sell New Homes When Existing Homes Are Too Cheap

When mortgage access dried up for families seeking to find affordable homes, the prices of those homes collapsed. Builders couldn’t profitably sell new homes because existing homes were cheaper than new homes.

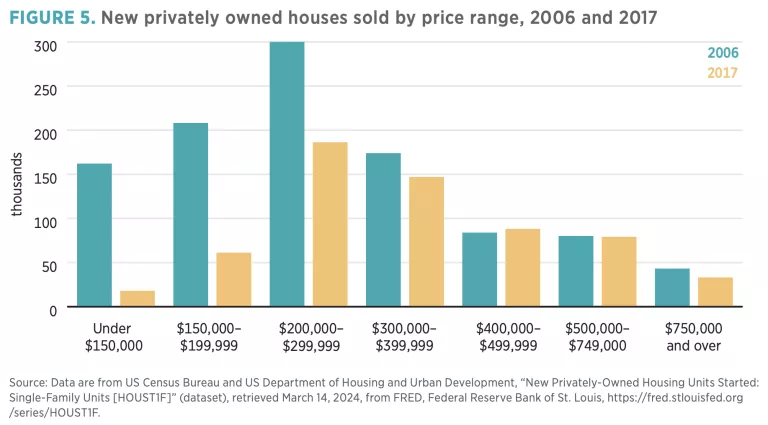

According to Zillow, the typical US home price peaked in 2006 at around $208,000.[8] The median home price didn’t rise back above that level until 2017. Figure 5 compares the sales of new homes in 2006 and 2017. Before the Great Recession, builders commonly sold half a million or more new homes priced below $200,000 each year. That number was down to 79,000 units by 2017.

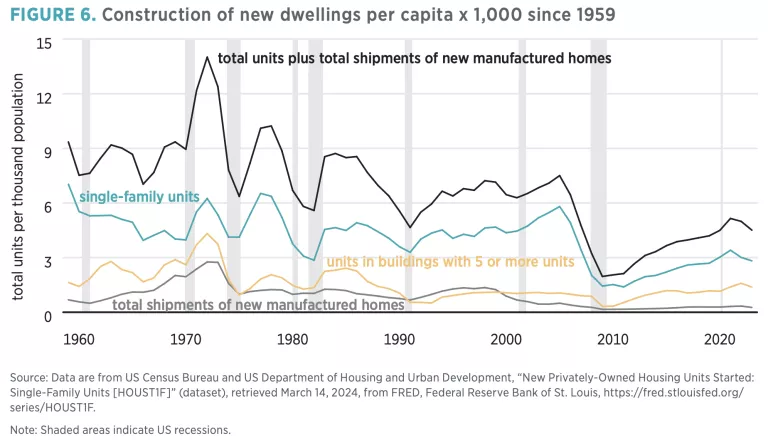

For decades before the Great Recession the US economy generally produced at least six new homes each year per 1,000 residents. (Today, that would amount to about 2 million units annually.) Figure 6 shows the number of manufactured homes, apartments, and single-family homes produced each year since 1959. The half million affordable units whose potential owners no longer were able to borrow has permanently been removed from our housing production capacity.

Before the Great Recession, about five single-family homes and one apartment were produced for every 1,000 Americans each year. But construction of apartments has been limited by onerous restrictions, and construction of new single-family, owner-occupied homes has been limited by demand (sales to families that can get mortgages are maxed out). Since it is limited to families that can get a mortgage, new single-family home sales now top out at two to three units per 1,000 Americans.

By 2019, the year before COVID, those two categories—apartments for rent and single-family homes for sale—were finally amounting to more than four units per 1,000 Americans, but that quantity still fell two units short of the long-term sustainable range.

When Builders Can’t Sell New Homes, Rents Rise

Builders haven’t been producing affordable homes below $200,000 because the prices of existing homes have been too low. The drop in prices was due to suppressed mortgage activity, not because of a decline in the demand for housing. For this reason, rents in affordable neighborhoods didn’t fall after 2008—only home prices did.

And since home prices in affordable neighborhoods were too low, buyers purchased existing homes instead of new homes. Rents on existing homes had to increase until prices of existing homes were once again higher than the cost of building new homes. Until that happened, new home builders had few buyers.[9]

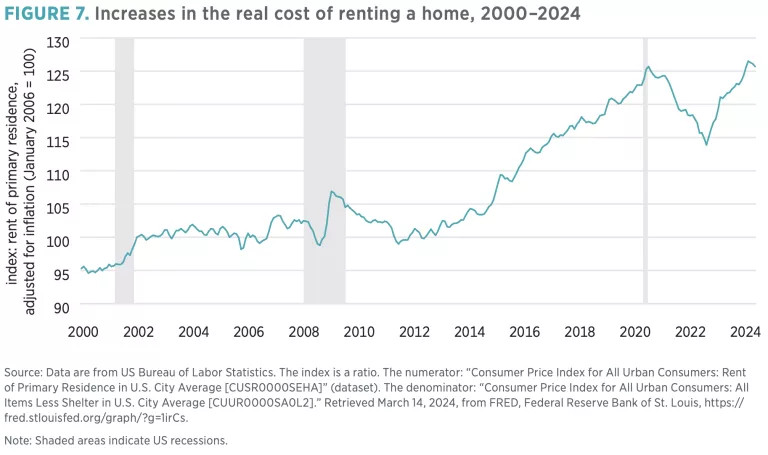

From 2012 to 2020, rents increased by an average of 25 percent after inflation, as shown in figure 7, and the rent increases were highest in neighborhoods with low incomes.[10] The historically low level of housing production has, predictably, been paired with unprecedentedly high rent inflation.

Institutional Investors Are Not to Blame for Rising Rents

As with rising prices, it is tempting to blame rising rents on institutional investors. But they are an implausible source of any significant rise in aggregate rents for the following reasons:

- By 2015, homeownership rates had finally bottomed out, and the number of owned homes was rising again. The marginal new demand for homes was coming from owners. Between 2014 and 2020, institutional buying slowed down considerably. [11]

- Large, institutional owners of single-family homes have never accounted for more than 2.5 percent of home purchases in any given quarter.[12]

- Large institutions are still an exceedingly small part of the entire market. They don’t account for even 1 percent of the single-family rental market.[13]

- For years, the market for new homes at prices that institutions were paying for existing homes has been practically nonexistent. If institutions were outbidding families for existing homes, those families could have bought new homes from builders who, during that time, were desperate for revenue. Tight mortgage standards led to discounted prices while keeping families from buying homes at those lowered prices.

The large institutions cannot plausibly be responsible for excessively high prices or rents. They simply don’t represent a large enough portion of the market. But there is no need to look for novel reasons for excessive rent appreciation. Annual housing production that is persistently half a million to a million units below a sustainable minimum is an obvious reason for rising rents.

When Builders Can Sell New Homes, Rents Stabilize

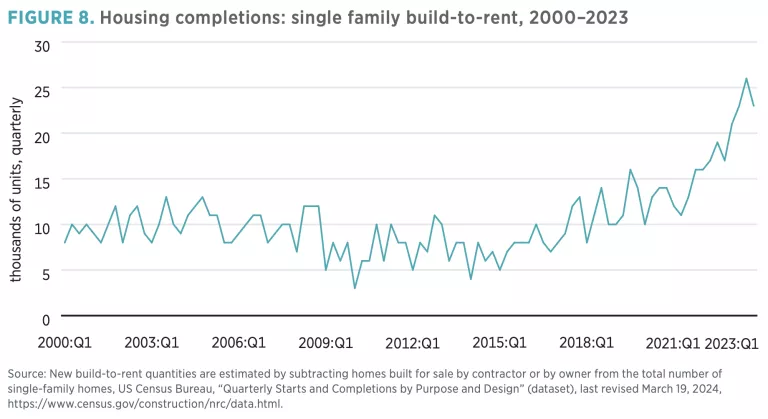

Rising rents are pushing existing home prices higher than the cost of new homes. Since the COVID-19 era, the buying activity of large institutional investors has increased again, but they have invested more in new homes. The number of new single-family homes built to rent has always been a very small market, but recently it has doubled. Completions are nearing 100,000 annually, or almost 10 percent of the new single-family market (figure 8).

Families that can still qualify for mortgages are buying homes just for themselves, and developers of apartment buildings are queued up at city planning departments, obstructed by regulatory barriers. New single-family homes for rent are the only category capable of significant marginal growth under current conditions. Mom-and-pop investors are not capable of buying hundreds of thousands of these homes or buying whole neighborhoods at a time in coordination with builders. This requires institutions capable of scale.

The growth of the large-scale, institutional market is key to stabilizing rents.

A Proper Accounting of the Role of Institutional Capital During the Past Decade

- After the Great Recession, institutional investors established a bottom for home prices in neighborhoods that suddenly were capital-poor.

- As owner-occupiers gradually reclaimed housing stock, existing home prices in those neighborhoods started to return to the price that it would cost to build new homes.

- While prices for existing homes in those neighborhoods remained below the price of new homes, rents increased as a growing population was forced to continue to fit into a limited supply of apartments and single-family rentals that were increasingly being purchased by new homeowners.

- Single-family homes in those neighborhoods have recently reached prices high enough to trigger new building. Institutional capital in single-family build-to-rent housing will finally be able to increase the supply of new rental housing.

- Corporate purchases of new homes built to rent may need to rise by hundreds of thousands of units annually—much higher than the buying activity corporations have engaged in so far—in order to stem the tide of rising rents.[14]

Large-Scale Institutional Landlords Are the Only Way to Address the Problem

American housing markets have been saddled with a number of limitations over the past century, most notably zoning and land use rules that block the production of new, denser infill housing. Then, in 2008, regulators and underwriters at the Federal Housing Administration, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac (Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation) greatly curtailed mortgage access, limiting the ability of families to purchase single-family homes in the suburbs and exurbs of our cities. One major institutional landlord estimates that 85 percent of its tenants cannot qualify for a mortgage under the current standards. [15]

Right now, the only market segment capable of filling the gap of supply at scale is large institutional landlords. If legislators block this source of new housing, the results may be too tragic to contemplate.

Policymakers should think long and hard about the consequences of banning this one remaining source of housing. The increasingly visible homeless encampments in our most expensive cities are just the tip of the iceberg. Americans are burdened by the lack of housing. It is imperative that we stem these trends.

The scale of corporate housing development necessary to stop rents from rising will continue to attract the ire of frustrated families and populist politicians. Until progress can be made to relegalize other forms of housing, disciplined and knowledgeable policymakers must support every avenue for keeping stressed American families housed.

About the Author

Kevin Erdmann is a senior affiliated scholar at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. He has engaged in research with Mercatus about housing finance, land use restrictions, and monetary policy. His first book, Shut Out: How a Housing Shortage Caused the Great Recession and Crippled Our Economy (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), offers a contrarian theory on the causes of the housing boom and bust and details a number of ways in which obstacles to housing supply affect the American economy. His second book, Building from the Ground Up: Reclaiming the American Housing Boom (Post Hill Press, 2022), reconsiders the policy decisions that led to the Great Recession and brought the housing market to the condition it is in today. Erdmann’s work has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Barron’s, National Review, USA Today, and Politico and has been featured on C-SPAN. Erdmann was a small business owner for 17 years and holds a master’s degree in finance from the University of Arizona.

Notes

- Heather Middleton, “No Renters: Clayton County Board of Commissioners Eliminates Builders’ Ability to Rent, Lease New Homes,” Clayton News (news-daily.com), April 12, 2021.

- Oscar De Los Santos and Juan Mendez, opinion, “Corporate Investors Sucked Up 1 of 3 Arizona Homes on the Market. That Must End,” azcentral, updated February 29, 2024.

- End Hedge Fund Control of American Homes Act, S.3402, 118th Cong. (2023).

- Daniel Herriges, “Going after Corporate Homebuyers Is Good Politics but Ineffective Policy,” Strong Towns, February 21, 2024.

- Kevin Erdmann, Shut Out: How a Housing Shortage Caused the Great Recession and Crippled Our Economy (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), 91–107.

- Kevin Erdmann, Shut Out, figures 3-7, 3-8, and 3-9.

- Lauren Lambie-Hanson, Wenli Li, and Michael Slonkosky, “Leaving Households Behind: Institutional Investors and the U.S. Housing Recovery” (FRB of Philadelphia Working Paper No. 19-1, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, January 2019).

- Zillow, Zillow Home Value Index (database), accessed April 13, 2024, https://www.zillow.com/research/data.

- Kevin Erdmann, “Rising Prices, Lower Rents; Rising Rents, Rising Prices” (Expert Commentary, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, June 2019).

- Kevin Erdmann, “Rising Home Prices Are Mostly from Rising Rents” (Mercatus Special Study, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, August 2022), 19. See also Kevin Erdmann, “Home Price Trends Point to a Worsening Lack of Supply” (Mercatus Special Study, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, May 30, 2023), 33–36.

- Caitlin Young, “Institutional Investors Brought Higher Home Prices and Lower Vacancies to the Housing Recovery,” Urban Wire (blog), Urban Institute, March 5, 2020.

- Danielle Nguyen and Josh Kirby, “Changing the Playbook: SFR Operators Pivot as Rates Rise,” Insights (blog), John Burns Research and Consulting, October 27, 2023.

- National Rental Home Council, Institutional Owners of Single-Family Rental Homes: Get the Facts, 2022, slide 11.

- Currently, reports of a wave of new supply are common, based on record high numbers of apartments under construction. However, the high number of units under construction is mostly a result of urban overregulation, which has doubled the amount of time units are under construction before they are completed. Completed units have been relatively flat since the start of COVID-19 and are unlikely to rise significantly in the near term—certainly not high enough to make much of a difference in housing supply. From the low annual base of apartment construction, now just over one unit per 1,000 Americans, apartment construction would need to double or triple to fill the gap to a sustainable housing supply. See Charles Gardner, “How to Streamline Housing Permitting in Connecticut” (Mercatus Policy Brief, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, January 2024), 2.

- Gene Burinskiy, The Profile of Single-Family Renters and the Barriers to Homeownership That Got Them Here (Austin, TX: Amherst Group, 2021), 4, https://www.amherst.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Profile-of-Single-Family-Renters.pdf.