- | Government Spending Government Spending

- | Research Papers Research Papers

- |

Why We Have Federal Deficits: The Policy Decisions That Created Them

In a new study published by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Charles P. Blahous, a Mercatus senior research fellow and public trustee for Medicare and Social Security, examines the causes of federal deficits by systematically examining the federal budget itself, quantifying all contributions to the deficit regardless of when they were enacted.

“Any strategy that fails to adjust the 1965–72 policy decisions—specifically, those creating the current designs of Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security—will inevitably fail to correct the federal government’s fiscal imbalance.”

—Charles P. Blahous

Washington will never gain control of federal budget deficits unless it clearly identifies their underlying causes. Yet many studies that purport to identify the policies and policymakers responsible for the imbalance focus only on policy decisions made during a narrow time period. Such a distorted approach often serves political ends, allowing partisans to lay blame at the feet of a president or Congress of the opposing party. Unfortunately, by excluding most of the relevant policy choices from view, this approach also results in misguided prescriptions—ostensibly aimed at “fixing” the budget—that inevitably fail to address the underlying problems.

In a new study published by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Charles P. Blahous, a Mercatus senior research fellow and public trustee for Medicare and Social Security, examines the causes of federal deficits by systematically examining the federal budget itself, quantifying all contributions to the deficit regardless of when they were enacted. Blahous presents three perspectives, based on comparisons of the components of the current fiscal imbalance with historical budget norms established over the past 40 years. These perspectives involve (1) identifying the policy decisions that underlie the projected fiscal imbalance; (2) examining the historical sources of the current-year deficit; and (3) quantifying the sizes of the deficits run during different officials’ times in office.

Below is a brief overview. To read the study in its entirety and learn more about its author, please see “Why We Have Federal Deficits: The Policy Decisions that Created Them.”

KEY FACTS

Long-Term Deficits

The vast majority—more than three-fourths—of the currently projected long-term fiscal imbalance derives from a set of decisions made between 1965 and 1972: specifically, the creation and subsequent expansion of Medicare and Medicaid and the automatic indexation of Social Security benefits.

- The long-term imbalance is driven primarily by growth in the costs of Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, and the new health-insurance exchanges established as part of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA).

- Any strategy that fails to reform the key drivers of projected long-term deficits—namely, these largest entitlement programs—will inevitably fail to correct the federal government’s fiscal imbalance.

- Recent political battles—over issues ranging from tax policy to overseas military operations to the 2009 stimulus package—have little to do with addressing projected long-term deficits. As a percentage of GDP,

- spending in all other budget categories (that is, all categories except Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, and the ACA’s health-insurance exchanges) is projected to decline significantly, and

- federal tax collections are projected to well exceed historical norms.

Current-Year Deficit

The current-year deficit exists largely because of growth in Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid spending, in combination with recent expansions of income security programs and lower-than-typical revenue collections.

Officials’ Records of Fiscal Stewardship

Measuring absolute deficits during policymakers’ times in office produces the finding that these deficits have been substantially higher during the current presidential administration than in any other period studied, by a wide margin.

SUMMARY

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that federal deficits and debt will ultimately reach untenable levels—the ultimate cost of which is reduced economic growth, higher tax burdens for fewer government services, and a lower standard of living for Americans. Washington’s ability to successfully address this problem requires an understanding of which current policies give rise to these projections, and the extent to which alteration of these policies can improve the fiscal outlook.

This study uses three methodologies to quantify the policy choices that contribute to the fiscal gap. None of these methodologies is inherently superior; each offers useful insights, and each has downsides. Viewed together, however, they reveal much about how federal deficits came to be.

First Perspective: The Policy Decisions That Drive the Long-Term Imbalance

This method compares the components of the current fiscal imbalance with historical budget norms established over the past 40 years to determine the incremental policy changes that have produced the projected long-term fiscal imbalance. It finds the following:

- More than three-fourths of the projected long-term fiscal imbalance derives from policies enacted between 1965 and 1972—specifically, those that created the current design of Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security.

- Most Medicare and Medicaid costs derive from the programs’ initial enactment in 1965 during the administration of President Johnson. They, along with Social Security, were also the objects of significant benefit expansions in 1972 during the Nixon administration.

- While Medicare has been changed many times since its enactment, most of the changes in the past several decades have reined in—rather than expanded—projected cost growth.

- Medicare’s cost problems are primarily a legacy of the program’s enactment; they embody a cautionary tale of how a program’s actual costs often exceed initial estimates.

- Most Medicare and Medicaid costs derive from the programs’ initial enactment in 1965 during the administration of President Johnson. They, along with Social Security, were also the objects of significant benefit expansions in 1972 during the Nixon administration.

- The fourth major driver of long-term deficits is the ACA’s new health-insurance exchanges. To date, these exchanges have not contributed significantly to federal deficits—but going forward, they are one of the largest drivers of federal spending growth and deficits.

- Over the long term, neither federal appropriations spending nor federal tax revenues play a significant role in structural deficits. As a percentage of GDP,

- federal revenues are projected to significantly exceed historical norms, and

- all appropriations (including military operations and other defense spending) will be significantly less than historical levels.

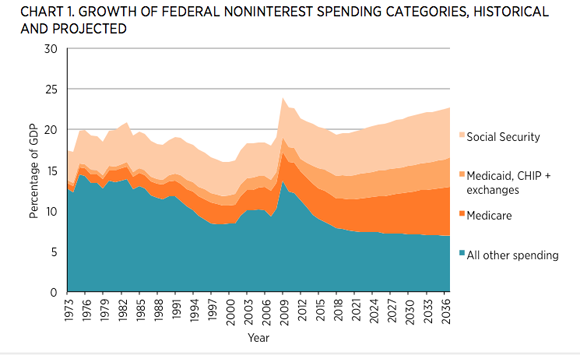

Chart 1 illustrates how spending on Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, and the ACA’s new health-insurance exchanges is projected to grow at a rate faster than the economy can sustain, while all other federal spending is projected to shrink in relative terms.

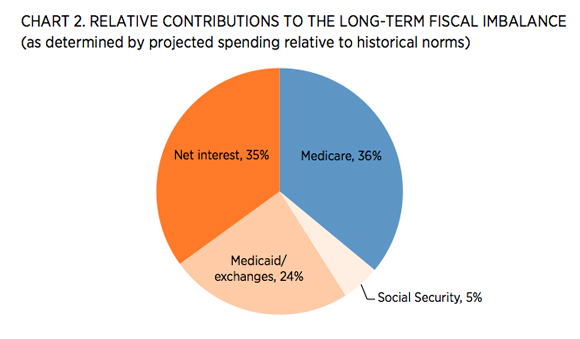

Chart 2 shows the relative size of the contributions of spending growth in various categories to the deficit projected for 2037, taking into account what would be affordable given the surpluses that CBO projects in other budget accounts.

Second Perspective: The Policy Decisions That Created the Current Year (FY2013) Deficit[1]

This method identifies the incremental policy decisions that led to the current fiscal year deficit. It finds that the causes of the current deficit are more diffuse than those of the long-term deficit:

- The current deficit exists largely because of recent surges in Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid spending relative to historical norms, in combination with recent expansions of income security programs and lower-than-typical revenue collections.

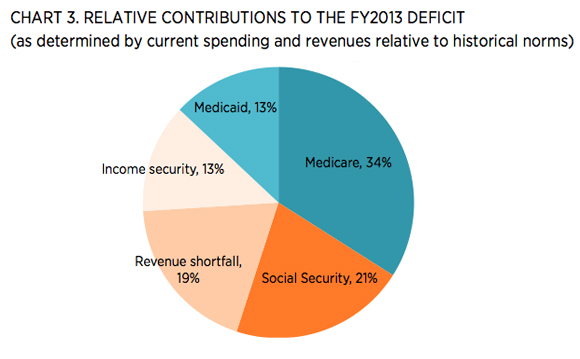

Chart 3 breaks down the factors driving the FY2013 deficit relative to 40-year historical norms.

Summarizing Contributions to the Deficit

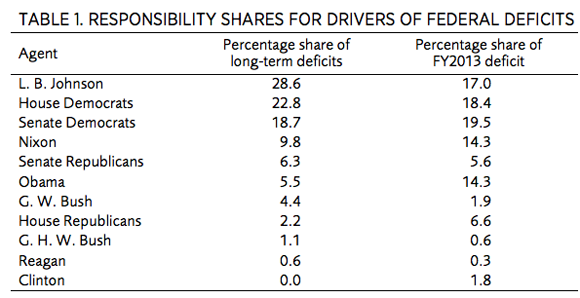

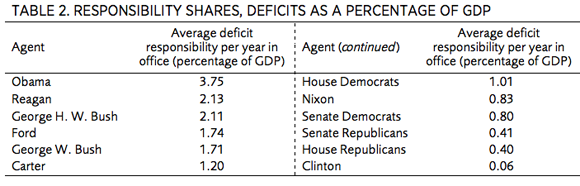

The study also contains an analysis in which 50 percent of the responsibility for budget policy is assigned to the president, 25 percent to the majority party in the House of Representatives, 20 percent to the majority party in the Senate, and 5 percent to the Senate minority. The results of varying these assumptions are also discussed in the study.

Table 1 summarizes the contributions of different officeholders to federal deficits under these assumptions, according to the two aforementioned perspectives.

Third Perspective: Officeholders’ Fiscal Stewardship Records

This method assigns responsibility for federal deficits according to their absolute levels during elected officials’ terms of office.

- This perspective is also important because often later officeholders have more information about the costs of federal programs than did the earlier officeholders who enacted them. Moreover, federal officials bear a responsibility to adjust policies to achieve sustainable federal finances, regardless of when those policies were enacted.

- These deficits have been substantially higher during the current presidential administration, by a wide margin, than in any other period studied.

[1] The study was conducted during FY2013