- | Regulation Regulation

- | Working Papers Working Papers

- |

Entry Regulation and Rural Health Care: Certificate-of-Need Laws, Ambulatory Surgical Centers, and Community Hospitals

We examine the effect of entry regulation on ambulatory surgical centers and community hospitals and find that there are both more rural hospitals and more rural ambulatory surgical centers per capita in states without a certificate-of-need program regulating the opening of an ambulatory surgical center. This finding indicates that certificate-of-need laws may not be protecting access to rural health care, but are instead correlated with decreases in rural access.

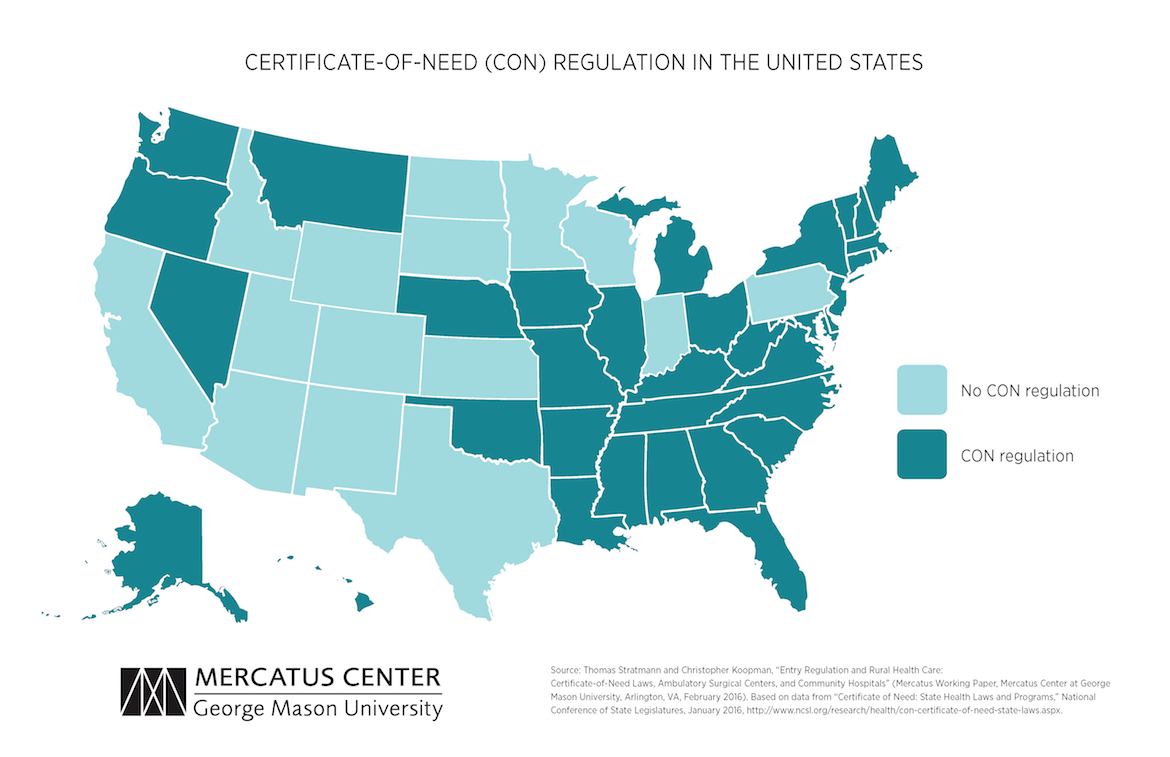

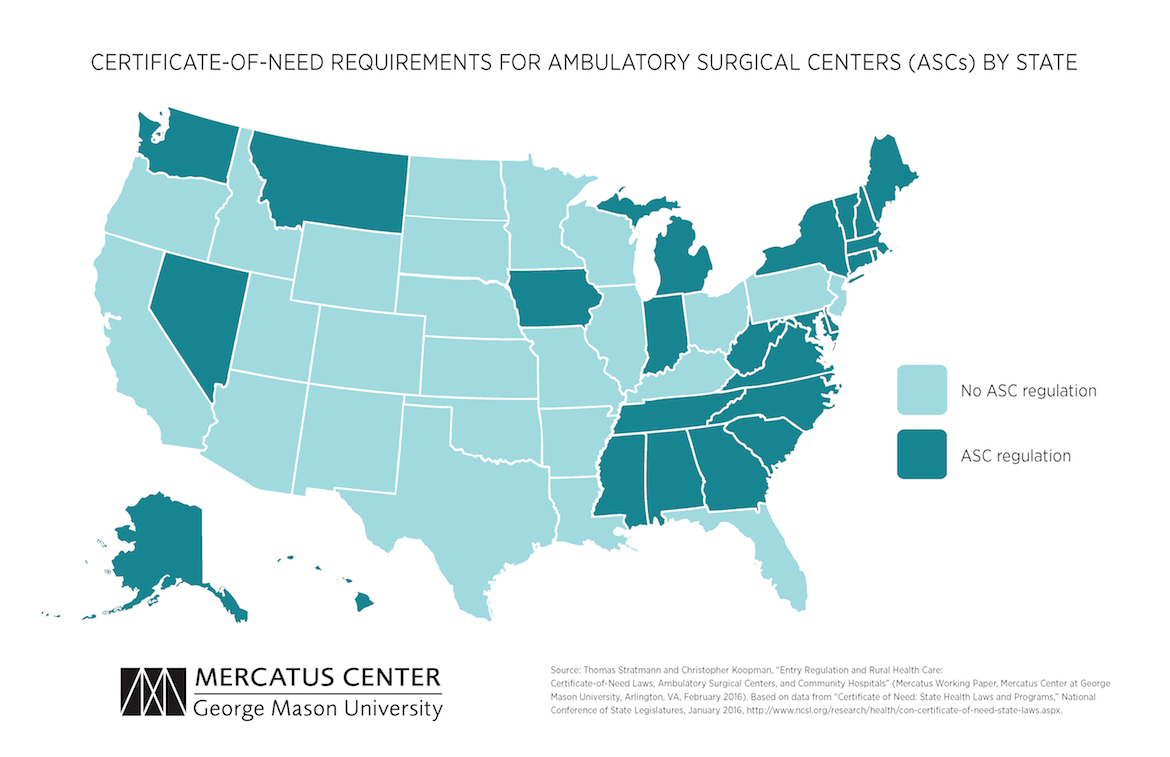

Certificate-of-need (CON) laws in 36 states and the District of Columbia restrict competition in healthcare facilities markets by requiring healthcare providers to obtain permission before adding or expanding any regulated facilities or services. One such CON program, currently implemented by 26 states, regulates the establishment and expansion of ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs), “hospital substitutes” that provide select out-patient surgeries and procedures.

Proponents of regulating ASCs through a CON program express concern that ASCs will engage in “cream skimming,” selectively treating more profitable, less complicated, well-insured patients and leaving hospitals to treat the less profitable, more complicated, and uninsured patients. Under these circumstances, ASCs might cause hospitals to close, especially rural hospitals with slim profit margins—thus depriving rural populations of important medical services.

In a new empirical study for the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, scholars Thomas Stratmann and Christopher Koopman evaluate the impact of ASC CON regulations on the availability of rural health care. Their research shows that, despite the expressed goal of ensuring that rural populations have access to health care, CON states have fewer hospitals and ASCs on average—and fewer in rural areas—than non-CON states.

BACKGROUND

History of Certificate of Need

CON programs, which originated in New York in 1964, were developed as an attempt to (1) control healthcare costs, (2) increase charity care, and (3) ensure the provision of rural care. State CON laws were a conditional requirement for receiving federal funding from 1974 until the repeal of the National Health Planning and Resources Development Act in 1986. Twelve states repealed their CON programs in the late ’80s, three states repealed them in the ’90s, and one state has repealed its CON program since 2000. Currently, 36 states and the District of Columbia operate some form of a CON program.

CON’s Third Policy Goal

Few prior studies have focused on whether CON laws affect the provision of rural health care, and the hypothesis that cream-skimming by ASCs will decrease access to care. The cream-skimming hypothesis suggests that ASCs will threaten the financial stability of hospitals by taking away their ability to subsidize the costs of complicated patients by revenue from less-complicated patients. Because rural areas may have only one or two hospitals, a hospital closure in a rural area could negatively impact access to care.

STUDY DESIGN

This study tests two related hypotheses to determine the impact of ASC regulation on the provision of health care in states with and without CON programs.

- The study uses two state-level annual measures of healthcare providers, the number of community hospitals per capita and the number of ASCs for the years 1984–2011, both obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Provider of Services (POS) file.

- Rural areas are defined as areas outside a core-based statistical area, a designation by the Office of Management and Budget for areas with at least 10,000 people, using the zip code of each facility provided in the POS file.

- State-level CON program data for 1992–2011 come from the American Health Planning Association’s annual survey; for state-level laws before 1992, the study uses HeinOnline’s Digital Session Laws Library.

- Socioeconomic control variables, population sizes, poverty level information, and racial and age demographics come from the Census Bureau. State nominal income data come from the Bureau of Economic Analysis and are converted to real income using the consumer price index from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, with 2011 as the base year. State-level unemployment data are taken from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Mortality rates because of lung cancer and diabetes by year and state for the population 18 years old and over are collected from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and are used to control for state health status.

KEY FINDINGS

CON Programs Are Associated with Fewer Hospitals

- The presence of a CON program is associated with 30 percent fewer hospitals per 100,000 residents across the entire state.

- The presence of a CON program is also associated with 30 percent fewer rural hospitals per 100,000 rural residents.

ASC-Specific CON Programs Are Effective Barriers to Entry for ASCs

- The presence of an ASC-specific CON is correlated with 14 percent fewer total ASCs per 100,000 residents.

- The presence of an ASC-specific CON is associated with 13 percent fewer rural ASCs per 100,000 rural residents.

CONCLUSION

The data do not support the cream-skimming hypothesis as a justification for CON programs. ASC-specific CON laws serve as effective barriers to entry for ASCs, both in rural areas and throughout the state. However, as barriers to entry, CON programs do not promote access to rural care in the form of rural hospitals. CON laws are associated with a decrease, not an increase, in the number of hospitals, rural or otherwise. Policymakers seeking to protect access to rural care should not use CON programs to achieve their goals.